As people go through their daily and nightly routines, their digestive tracts follow a routine, too: digesting food and absorbing nutrients during waking hours, and replenishing worn-out cells during sleep. Shift work and jet lag can knock sleep schedules and digestive rhythms out of whack. Such disruptions have been linked to increased risk of intestinal infections, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer, among other things.

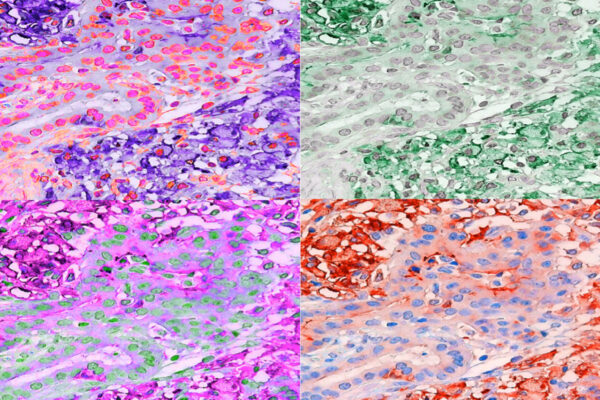

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a type of immune cell that helps keep time in the gut. Such cells, known as type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3), are responsible for keeping the intestine operating in a normal, healthy manner. The researchers found that so-called clock genes are highly active in such cells and that the cells’ production of immune molecules track with the activity of the clock genes. When the researchers eliminated a key clock gene from mice, the animals failed to produce a subset of ILC3 cells and struggled to control a bacterial infection in the gut.

The findings, published Oct. 4 in Science Immunology, help explain why disruptions to circadian rhythms are linked to gastrointestinal problems. Further, they suggest that targeting clock genes could affect immune cells and help counter the negative effects of erratic sleep schedules associated with intestinal illnesses.

“It’s become increasingly clear that the disruptions of circadian rhythms so common in modern life — shift work, jet lag, chronic sleep deprivation — have harmful effects on people’s health, but we still don’t know a lot about how exactly sleep disruptions cause these problems,” said senior author Marco Colonna, MD, the Robert Rock Belliveau MD Professor of Pathology and a professor of medicine. “What we’ve found here is that circadian rhythms directly affect the function of immune cells in the gut, which could help explain some of the health issues we see, such as inflammatory bowel disease and metabolic syndrome.”

ILC3 cells maintain equilibrium in the gut by fortifying the barrier between the trillions of bacteria that normally live inside the gut and the cells that make up the intestine itself. They also produce immune molecules that help the gut’s immune system avoid overreacting to harmless microbes and food particles, while preserving its ability to combat disease-causing micro-organisms.

Colonna and colleagues have studied ILC3 cells for years, but it wasn’t until first author Qianli Wang and second author Michelle Robinette, MD, PhD – both graduate students in Colonna’s lab at the time – noticed that clock genes were highly activated in ILC3 cells that they began to wonder whether the cells could link circadian rhythms to the gut’s immune system.

“If ILC3 cells are attuned to circadian rhythms, they can anticipate when nutrition is going to arrive in the intestine, which is also when dangerous bacteria might accidentally be consumed and arrive in the gut, too,” Wang said. “For optimal functioning, the gut needs to be prepared for these daily rhythms, and these cells play a pivotal role in that process.”

By studying ILC3 cells taken from mouse intestines at six-hour intervals, the researchers found that the activity of clock genes varied in a predictable pattern over the course of a day, and that the activity of genes for immune molecules tracked with the clock genes. When they put some mice on a schedule similar to one experienced by a shift worker – an eight-hour change in the light-dark cycle every two days – the ILC3 cells no longer functioned normally. They produced low levels of immune molecules when stimulated to respond to an infection. Further, when mice were genetically modified to lack the clock protein REV-ERB alpha, the animals failed to develop normal quantities of ILC3 cells.

“I think it’s fair to say that ILC3 is under circadian rhythm regulation and certain key circadian genes are crucial for ILC3 cells to develop and function,” Wang said.

Wang and Colonna suspected that a paucity of ILC3 cells or a change in ILC3 behavior could affect the body’s ability to fight intestinal infections. Using mice that lack the clock protein – as well as healthy mice for comparison – the researchers studied the effect of infection with the bacterium Clostridium difficile, which can cause severe diarrhea in people. The mice without the clock protein failed to mount an effective defense: Their ILC3 cells produced more of a damaging immune molecule and less of a protective immune molecule, and the bacteria spread more widely in their bodies.

“The equilibrium of the gut is upset by disruptions to circadian rhythms,” Wang said. “ILC3 cells are so important to gut equilibrium that we may be able to counter some of these disruptions by targeting clock genes in ILC3 cells.”

The researchers are continuing to study the role of circadian rhythms on the digestive tract.

“The emerging relevance of the circadian regulation in gut health is likely to impact medical and hospital practice,” Colonna said. “I think we will have to start taking circadian rhythms of the gut cells into consideration when choosing optimal timing for nutritional and pharmacological interventions.”