Dick Powis, a PhD candidate in anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, likes to joke that if a picture is worth a thousand words, then he should be allowed to submit 100 photographs for his dissertation.

“As an anthropologist, my job is to write about cultures and people, but I’ve always believed that photography can be an equally important tool in an anthropologist’s tool box,” said Powis, who brings multiple cameras and even dark-room supplies on his research trips to Dakar, Senegal.

Powis’ photo of Senegalese griots — praise singers — recently won third place in the Department of Anthropology’s annual photo contest. Glenn Stone, professor of sociocultural anthropology and of environmental studies in Arts & Sciences, started the contest about a decade ago as a way to showcase the stunning photography his students bring back from the field.

“Photography and anthropology are old friends,” said Stone, whose own photography from research trips to India, the Philippines and Nigeria has won national awards. “We take photos for scientific documentation and to help us remember the things we learn. We also take photographs to give to the people we meet. And then there are the aesthetics. We often find ourselves in places that are striking.”

Here, The Source visits with contest finalists Powis and Tashi Ghale, also a PhD candidate, whose image won second place, about their photography and research.

What came first: your interest in photography or in anthropology?

Powis: I’ve been thinking about both since I’ve been very young. My dad was in the military, so I have been introduced to new environments and people my whole life. And photography has always been an important outlet and form of artistic expression for me. Most anthropologists don’t get any formal training in photography, but I took a class at the Sam Fox School because I really love it as an outlet and form of artistic expression.

Tell us about your research.

Powis: My research is about expectant fatherhood, specifically women’s health and how men perceive and influence women’s health. In Dakar, men have what we would think of as a distant relationship to pregnant women. Men call pregnancy women’s business. That transfers over to childrearing, gendered labor and many aspects of life. That said, (Senegalese) men do care a lot, just differently than we do.

What’s going on in the picture of the griots?

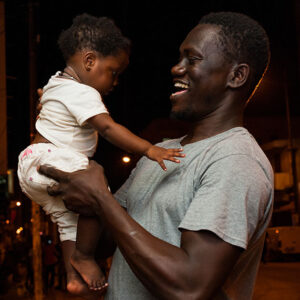

Powis: This photo is special to me. When I was an undergrad at Cleveland State University, my adviser was a photographer and a filmmaker whose background was working in Mali. She did some of her earliest work on griots, who are praise singers, but much more. They are musicians, dancers and genealogists, and they are present at every major life event, such as weddings, baptisms and funerals. They will show up and sing and dance about the family that is being celebrated.

In this case, the griots are singing at the naming ceremony of the baby who is, in essence, my niece, Oumou. The father is my good friend and “brother.” I have been living with his family during my visits, and they have given me their last name. So when the griots sang about the family, they sang about me.

What is happening in your prize-winning photograph?

Ghale: I took this photo in the Himalayan highlands during the yarsagumba season. Yarsagumba (a parasitic fungus that infects caterpillars) is used for medicinal purposes and is extremely rare and valuable. It can only be found in June and July, and each worm is worth $5 to $10. The money they earn during the yarsagumba season can last a year. But because of ecological changes and overharvesting, it is harder and harder to find. This is having a big effect on villagers because there aren’t other sources of income.

Who is the woman in your photograph?

Ghale: Her name is Dolkar. She is the mother of a friend who is a traditional doctor. I always ask before I take pictures, and she said I could photograph her. There is a trust that has grown between us. She will work all day, bent over and in the cold. The altitude is at least 4,000 to 5,500 meters (13,000 to 18,000 feet), so there is a lack of oxygen, too. It is dangerous work.

Why is photography important to your work?

Ghale: I chose photography because it helps me understand what I see. There are demerits in that you can only capture a frame — not all that leads up to or follows a moment. But it is one of the best mediums to follow people at margins (and their activities), who are generally silenced or ignored.