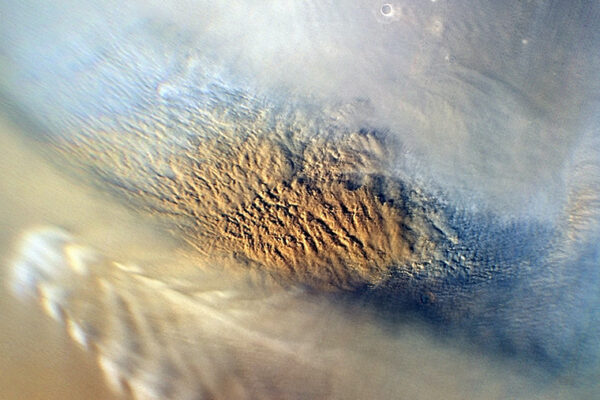

The Earth has been through a lot of changes in its 4.5 billion year history, including a shift to start incorporating and retaining volatile compounds from the atmosphere in the mantle before spewing them out again through volcanic eruptions.

This transport could not have begun much before 2.5 billion years ago, according to new research by Washington University in St. Louis, published in the Aug. 9 issue of the journal Nature.

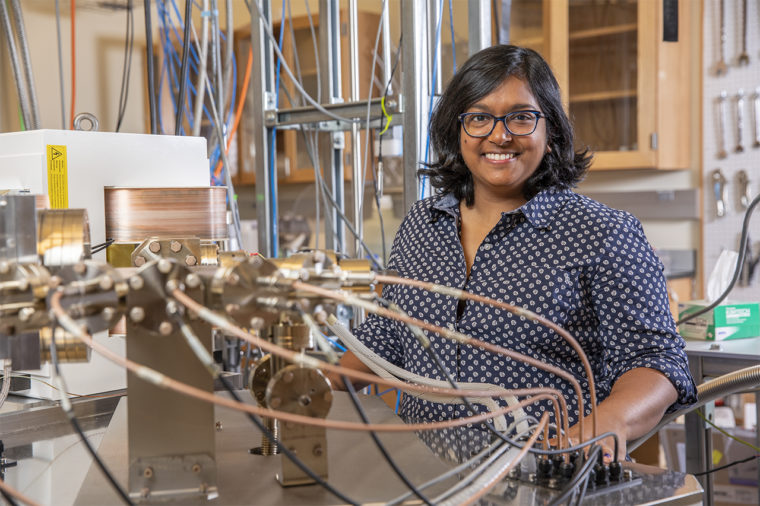

“Life on Earth cares about changes in the volatile budget of the surface,” said Rita Parai, assistant professor of geochemistry in Earth and Planetary Sciences in Arts & Sciences and first author of the study. “And there’s an interplay between what the deep Earth was doing and how the surface environment changed over billion-year timescales.”

Volatiles — such as water, carbon dioxide and the noble gases — come out of the mantle through volcanism and may be injected into the Earth’s interior from the atmosphere, a pair of processes called mantle degassing and regassing. The exchange controls the habitability of the planet, as it determines the surface availability of compounds that are critical to life — such as carbon, nitrogen and water.

The new model presented by Parai and collaborator Sujoy Mukhopadhyay, of the University of California, Davis, also establishes a range of dates during which the Earth shifted from a net degassing regime — again, think about those oozy volcanoes — to one that tilted the balance to net regassing potentially enabled by subduction, the conveyor-belt action of tectonic plates.

Mechanical properties change as water is added or removed from the mantle, so the onset of regassing had an important effect on the internal churning of the mantle, known as convection, which controls plate motions at the surface, Parai said.

Parai uses noble gases to address questions about how planetary bodies form and evolve over time. In this new research, she modeled the fate and transport of volatile compounds into the Earth’s mantle using xenon isotopes as tracers.

“Xenon is an excellent volatile tracer, because all minerals that carry water also carry xenon,” Parai said. “So if xenon regassing was negligible, water regassing must also have been negligible during the Archean (4 billion-2.5 billion years ago).”

Substantial regassing began sometime between a few hundred million to 2.5 billion years ago, the researchers found.

If plate tectonics and subduction began earlier than 2.5 billion years ago, then perhaps by then the Earth’s interior had cooled sufficiently for volatiles to remain in subducting plates, rather than getting released and percolating back to the surface through magmatism, Parai suggests.

“Most people rarely have an occasion to think about volatiles trapped in the Earth’s interior,” Parai said. “They’re present at low concentrations, but the mantle is huge in terms of mass. So for the Earth’s total volatile budget, the mantle is an important reservoir.”

She plans to focus her future research on pushing the limits of precision in xenon isotopic measurements in a variety of geological samples.

“The more observational constraints we have, the better,” she said.