Research led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to issue new treatment guidelines aimed at accelerating global elimination of lymphatic filariasis – a devastating tropical disease.

An estimated 70 million people worldwide are infected with lymphatic filariasis, a parasitic disease spread by mosquitoes. The disease can cause massive swelling of lymph glands in the legs and lower body, resulting in long-term disability and social stigma.

Efforts to eliminate the disease have focused on treating entire populations of people living in areas where the disease is endemic, regardless of whether they are sick or not. Such a strategy is aimed at curing existing infections and preventing new ones.

The new WHO guidelines, announced in November, recommend a three-drug treatment regimen rather than the standard two-drug combination. The guidelines are based on studies in Asia and Africa led by Gary Weil, MD, a Washington University infectious disease specialist, and his international colleagues. Their results have demonstrated that adding ivermectin to the standard combination of diethylcarbamazine and albendazole is more effective than the two-drug regimen and just as safe.

An estimated 800 million people in 53 countries live in areas where lymphatic filariasis is transmitted. Residents in many of these areas could benefit from the three-drug regimen, Weil said.

In support of WHO’s new treatment recommendation, Merck & Co. recently announced that it would expand its donation program of Mectizan (Merck’s brand of ivermectin), making the drug available to an additional 100 million people annually.

“This new treatment has the potential to significantly shorten the time required to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in many countries around the world,” said Weil, a professor of medicine and of molecular microbiology. “WHO’s recent policy change together with Merck’s expanded donation of Mectizan should aid distribution of the three-drug regimen to many millions of people in dozens of countries where people are infected with lymphatic filariasis.”

The improved effectiveness of the new treatment is projected to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in most endemic areas within three years if enough people participate by taking the medications, which are provided for free. The WHO recommends that the triple-drug combination be distributed annually in areas where the standard two-drug regimen has not been effective or has not yet begun.

The most devastating effects of lymphatic filariasis occur when the thread-like parasitic worms that cause the disease migrate from the blood into lymphatic vessels. The worms grow and mature over a period of months and can cause blockage of the flow of lymph fluid, resulting in severely swollen legs, a condition known as elephantiasis, and genitals. Recent estimates suggest that about 35 million people are disfigured by the disease.

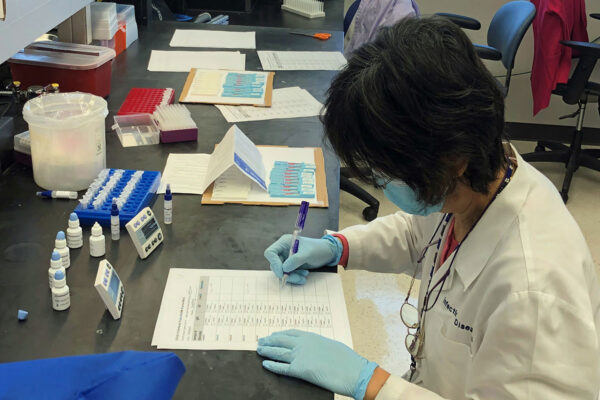

Washington University has played a key role in WHO’s Global Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis, which started in 2000 and provides treatment to about 500 million people annually. Weil’s earlier research led to an improved diagnostic test for the infection that is part of the global program.

An $8 million grant last year from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation allowed Weil and his colleagues to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the triple-drug treatment with studies of more than 23,000 people in India, Haiti, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. The foundation recently awarded Weil’s research team an additional two-year, $2.2 million grant to continue to study the impact of this new treatment.

“The global program has made great progress since its inception in 2000, but many countries have a long way to go to eliminate lymphatic filariasis,” Weil said. “With this new approach to treatment and continued effort and support, we are optimistic that the global health community can permanently rid the world of this disease.”