Investigating the harmful health effects of excess fat, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a protein that triggers death in mammalian cells overloaded with saturated fat.

When the researchers halted production of this protein, called EF1A-1, the cells were able to thrive in ordinarily damaging amounts of the saturated fat palmitate, a fat abundant in Western diets. At the same concentration of palmitate, normal cells still producing EF1A-1 rapidly died. The study will be published in the February 2006 issue of Molecular Biology of the Cell.

“When lipids (fats) accumulate in tissues other than adipose tissue, cellular dysfunction or cell death results,” says senior author Jean Schaffer, M.D., associate professor of medicine and of molecular biology and pharmacology. “For example, preliminary studies on animals suggest that the accumulation of fat in the pancreas contributes to the development of diabetes, and accumulation of lipids in skeletal muscle of leads to insulin resistance.”

Other studies have linked the genesis of heart failure to fat-induced cell dysfunction and cell death in the heart.

“As physicians our primary focus in diabetic patients is on glucose control,” says Schaffer, a member of the Center for Cardiovascular Research at the School of Medicine and a cardiologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “But it appears we should also be more aggressive with respect to lowering lipids such as triglycerides and fatty acids.”

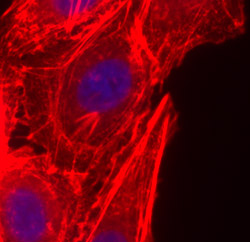

With the discovery of EF1A-1’s role, this study is the first to identify a critical step in the pathway that leads from high cellular fat to cell death, according to Schaffer. EF1A-1 is an extremely abundant protein with several diverse functions within cells, including protein synthesis and maintenance of the cytoskeleton, the cell’s internal support structure.

In mammalian cells grown in culture, the researchers saw that EF1A-1 and the fat palmitate work hand in hand: the presence of EF1A-1 dictated sensitivity to palmitate-induced cell death, and palmitate caused a rapid increase of the amount of EF1A-1 produced.

Schaffer’s laboratory earlier had developed a transgenic mouse that accumulates fat in its heart muscle cells resulting in the death of cells, heart failure and premature death. They found that EF1A-1 was increased nearly three-fold in the hearts of these animals.

Removal of EF1A-1 protected cells from palmitate-induced death, and its absence allowed cells to withstand assault by highly reactive oxygen molecules. According to study authors, this indicates that EF1A-1 probably contributes to cell death from oxidative stress, which is known to stem from high lipid levels. Cytoskeletal changes seen in cells missing EF1A-1 suggested to the researchers that EF1A-1’s cytoskeletal role also is important in cell death resulting from fat overload.

“Cells have a lot of mechanisms for incorporating fatty acids into storage forms, for metabolizing them or for using them in cellular membranes,” Schaffer says. “But saturated fats like palmitate are poorly stored in the tiny fat droplets normally found in most cells and therefore are more likely to enter into pathways that lead to cell death such as the one in which EF1A-1 is involved.”

In the process of identifying the role of EF1A-1, the lab members uncovered other proteins implicated in the toxicity of excess fats. They are now investigating each to find out what part it plays.

Future investigations by Schaffer’s research team will study the EF1A-1 protein to see whether fatty molecules directly alter the protein, or if they cause it to relocate within the cell.

Borradaile NM, Buhman KK, Listenberger LL, Magee CJ, Morimoto ETA, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. A critical role for eukaryotic elongation factor 1A-1 in lipotoxic cell death. Molecular Biology of the Cell, February 2006.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Washington University School of Medicine—Pharmacia Biomedical Program (JES) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.