Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a method to predict when someone is likely to develop symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease using a single blood test.

In a new study published Feb. 19 in Nature Medicine, the researchers demonstrated that their models predicted the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms within a margin of three to four years. This could have implications both for clinical trials developing preventive Alzheimer’s treatments and for eventually identifying individuals likely to benefit from these treatments.

More than 7 million Americans live with Alzheimer’s disease, with health and long-term care costs for Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia projected to reach nearly $400 billion in 2025, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. This massive public health burden currently has no cure, but predictive models could help efforts to develop treatments that prevent or slow the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

“Our work shows the feasibility of using blood tests, which are substantially cheaper and more accessible than brain imaging scans or spinal fluid tests, for predicting the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms,” said senior author Suzanne E. Schindler, MD, PhD, an associate professor in the WashU Medicine Department of Neurology. Schindler noted that these models could allow clinical trials of potentially preventive treatments to be performed within a shorter time period.

“In the near term, these models will accelerate our research and clinical trials,” she said. “Eventually, the goal is to be able to tell individual patients when they are likely to develop symptoms, which will help them and their doctors to develop a plan to prevent or slow symptoms.”

Protein forecasts symptom onset

The study was part of a project developed and launched by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health Biomarkers Consortium, a public-private partnership of which WashU Medicine is a member.

The models that Schindler and her colleagues developed use a protein called p-tau217 in an individual’s plasma, the liquid part of the blood, to estimate the age when they will begin experiencing symptoms of the neurodegenerative disease. Levels of p-tau217 in the plasma can currently be used to help doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s in patients with cognitive impairment. These tests are not currently recommended in cognitively unimpaired individuals outside of clinical trials or research.

To identify the interval between elevated p-tau217 levels and Alzheimer’s symptoms, Schindler and lead author Kellen K. Petersen, PhD, an instructor in neurology at WashU Medicine, analyzed data from volunteers in two independent long-running Alzheimer’s research initiatives: the WashU Medicine Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (Knight ADRC) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), based at multiple sites in the U.S. The participants included 603 older adults who lived independently in the community.

Plasma p-tau217 was measured with PrecivityAD2, a clinically available diagnostic blood test for Alzheimer’s disease from C2N Diagnostics, a WashU startup co-founded by WashU Medicine researchers David M. Holtzman, MD, the Barbara Burton and Reuben M. Morriss III Distinguished Professor, and Randall J. Bateman, MD, the Charles F. & Joanne Knight Distinguished Professor of Neurology, both coauthors on the study. Plasma p-tau217 was also measured in the ADNI cohort using blood tests from other companies, including one cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

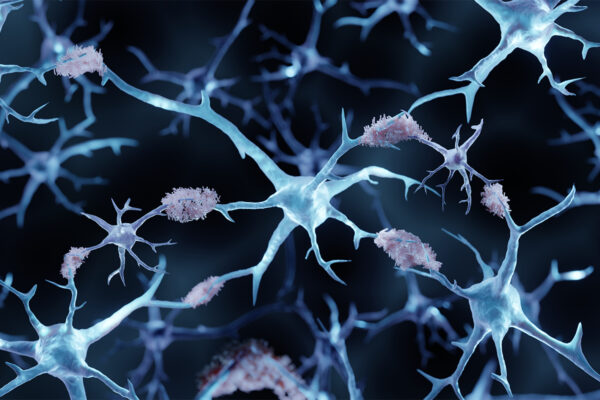

Plasma p-tau217 has previously been shown to correlate strongly with the accumulation of amyloid and tau in the brain as shown on PET scans. The key hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid and tau are misfolded proteins that begin building up in the brain many years before Alzheimer’s symptoms develop.

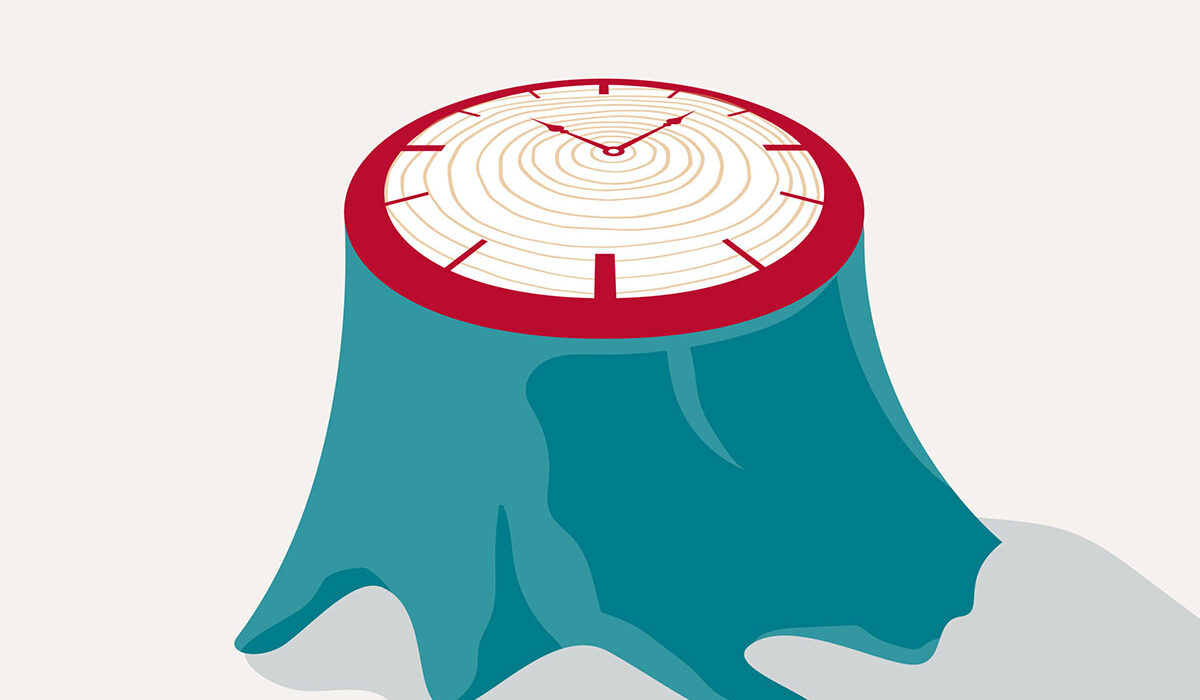

“Amyloid and tau levels are similar to tree rings — if we know how many rings a tree has, we know how many years old it is,” Petersen said. “It turns out that amyloid and tau also accumulate in a consistent pattern and the age they become positive strongly predicts when someone is going to develop Alzheimer’s symptoms. We found this is also true of plasma p-tau217, which reflects both amyloid and tau levels.”

The models predicted the age of symptom onset within a margin of error of three to four years. Older individuals had a shorter time from when elevated p-tau217 appeared to the start of symptoms as compared to younger participants, suggesting that younger people’s brains may be more resilient to neurodegeneration and that older people may develop symptoms at lower levels of Alzheimer’s pathology. For example, if a person had elevated p-tau217 in their plasma at age 60, they developed symptoms 20 years later. If p-tau217 wasn’t elevated until age 80, they developed symptoms only 11 years later.

The team found that their predictive model worked with the other p-tau217-based diagnostic tests for Alzheimer’s disease besides PrecivityAD2, illustrating the robustness and generalizability of their approach.

The authors shared all code for development of the models so that other researchers can further refine the models. Additionally, Petersen developed a web-based application allowing researchers to explore the clock models in greater detail.

“These clock models could make clinical trials more efficient by identifying individuals who are likely to develop symptoms within a certain period of time,” Petersen said. “With further refinement, these methodologies have the potential to predict symptom onset accurately enough that we could use it in individual clinical care.”

Petersen added that additional blood biomarkers are associated with cognitive symptoms in Alzheimer’s; as a direction for future research, these could be used to refine the estimates of symptom onset.

Petersen KK, Milà-Alomà M, Li Y, Du L, Xiong C, Tosun D, Saef B, Saad ZS, Du-Cuny L, Coomaraswamy J, Mordashova Y, Rubel CE, Meyers EA, Shaw LM, Dage JL, Ashton NJ, Zetterberg H, Ferber K, Triana-Baltzer G, Baratta M, Rosenbaugh EG, Cruchaga C, McDade E, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Sabandal JM, Bateman RJ, Bannon AW, Potter WZ, Schindler SE. Predicting onset of symptomatic Alzheimer disease with a plasma %p-tau217 clock. Nature Medicine. Feb. 19, 2026. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-026-04206-y

The results of the study represent results of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium “Biomarkers Consortium, Plasma Aβ and Phosphorylated Tau as Predictors of Amyloid and Tau Positivity in Alzheimer’s Disease” Project. The study was made possible through the scientific and financial support of industry, academic, patient advocacy, and governmental partners. Funding partners of the project include AbbVie Inc., Alzheimer’s Association®, Diagnostics Accelerator at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Biogen, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Private-sector funding for the study was managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

The Biomarkers Consortium, Plasma Aβ and Phosphorylated Tau as Predictors of Amyloid and Tau Positivity in Alzheimer’s Disease Project was made possible through a public-private partnership managed by the Foundation for the National Institute of Health (FNIH) and funded by AbbVie Inc., Alzheimer’s Association®, Diagnostics Accelerator at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Biogen, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Statistical analyses were supported National Institute on Aging grant R01AG070941.

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wpcontent/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

About WashU Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with more than 3,000 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 83% since 2016. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently among the top five in the country, with more than 2,000 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations. WashU Medicine physicians exclusively staff Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals — the academic hospitals of BJC HealthCare — and Siteman Cancer Center, a partnership between BJC HealthCare and WashU Medicine and the only National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in Missouri. WashU Medicine physicians also treat patients at BJC’s community hospitals in our region. With a storied history in MD/PhD training, WashU Medicine recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

Originally published on the WashU Medicine website