The teachers are dedicated; the principal is driven. And yet, Oak Hill Elementary School in the St. Louis Public School District recorded some of the region’s lowest language arts test scores.

“It was frustrating, because this is a wonderful team that comes to work every day ready and willing to do their best by their students,” principal Karessa Morrow said. “But we struggled to meet the unique challenge at our school.”

English is a second language for half of Oak Hill’s 320 students. Located in the Bevo neighborhood of south St. Louis, the school serves a large Hispanic and Bosnian population. But that’s not all. Among the languages students speak are Arabic, Vietnamese, Chinese and Pashtu — 16 languages in all.

To improve student performance, Morrow knew she needed more than devoted teachers, which she knew she had; she needed data-driven solutions. So she contacted Washington University in St. Louis applied linguistics expert Cindy Brantmeier, PhD, professor of applied linguistics and education in Arts & Sciences, chair of the Department of Education, and principal investigator in the university’s Language Research Laboratory.

Brantmeier has traveled the globe conducting research on how people acquire multiple languages, but Oak Hill presented an opportunity to serve educators in her own community. She immediately volunteered to provide free, ongoing professional development.

“A local school with 16 languages is rare and amazing,” said Brantmeier, who speaks Spanish, and is a user of French, Portuguese and Chinese. “Some people would see that language diversity as a deficit, but I see it as something to celebrate.

“Teachers do not need to be fluent in these languages to serve these learners, but they can be culturally and linguistically responsive,” she said. “That’s where I knew I could help.”

Brantmeier, with the help of her graduate students, decided to first tackle reading comprehension — an Oak Hill weakness, according to a report by the Missouri Assessment Program (MAP). English language learners often don’t fully understand common American concepts or the multiple meanings of a single word. For example, some students were stumped by a test question involving a fast food drive-thru restaurant. Without understanding the central concept, they could not draw conclusions.

This confusion extends to other subjects as well. In math, teachers often ask students to fill in the missing number. But why would anyone miss a number?

“They understand missing in the context of, ‘I miss you,’ ” Brantmeier said. “But that is a feeling. So students read that sentence and understand it to mean that they are supposed to feel sad because they miss a number.

“There were a lot of key lexical items that the students did not understand, and teachers were never trained to teach language,” she said.

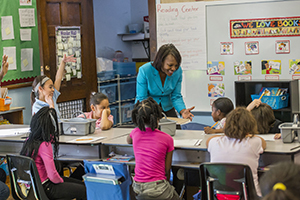

Brantmeier provided that training, introducing teachers to theory and research, and sharing of real-world solutions. One strategy: Make reading a social act in class instead of a silent activity at home. Then ask students to write down everything they remember from a given passage.

“The idea is to get them familiar with the idea that they will be responsible for generating output based on what they just read,” Brantmeier said.

Soon, teachers were contacting Brantmeier with questions, and she gave them her best answers:

Should students be allowed to speak their native languages? Yes. Students who are banned from using their native language may shut down at school.

Should students copy vocabulary words? No. Research shows rote copying does not benefit students.

Should a student be pulled out of class for extra support? It depends. Teachers should consider the student’s unique learning style.

“They would write, ‘How can I address this tomorrow?’ And I would shoot them back an email saying, ‘Try this, try this, try this. Research suggests this will work, let’s try it in your room,’ ” Brantmeier said.

Meanwhile, Morrow introduced her own initiatives. Students are now required to read 30 minutes daily and are assessed every five weeks. A colorful mural in Oak Hill’s front hallway tracks how many students read at grade level.

The Washington University Books and Basketball community service organization also contributed to the cause. University students started to visit four times a week to play basketball and help with homework. That made a big difference for kids whose parents couldn’t help at home because they are not fluent in English.

The results have been remarkable. Oak Hill’s MAP English language arts score jumped from 12.6 percent proficient in 2014 to 32 percent proficient in 2015. The school is now fully accredited.

“This is just the start,” Morrow said. “This professional development gave teachers a better understanding of the current research and the best practices. Dr. Brantmeier got teachers to ask themselves, ‘How do I push my thinking about different languages and cultures?’ ”

Cheryl Castiaux is one of those teachers.

“All of our students, not just our English language learners, have benefitted from these approaches,” said Castiaux, a 30-year teaching veteran. “We all have a lot of experience in the classroom, but it’s important to know what the research says so we can be effective.”

Brantmeier isn’t finished. This year, she and her college students returned to help teachers improve elementary student vocabulary. At a recent workshop, she offered teachers some simple tips, such as highlighting new words; connecting words with pictures; and providing vocabulary instruction throughout the day across subjects.

She showed teachers effective vocabulary games and busted some common language myths. “No,” she told them. “It does not help to memorize long lists of vocabulary words. We want students to acquire language, not memorize it. Learners need to do something with the new language.”

Brantmeier also told teachers she wants them to explore how a student’s confidence and self-esteem can impact learning. She shared that her stomach still tightens whenever she thinks about her first Chinese professor.

“He always put us on the spot — I hated the stress,” Brantmeier recalled. “It can be intimidating for your students, too, to be on the playground running and speaking in Spanish, and then return to the classroom and have to speak English.

“How can we lower the anxiety level to increase their confidence? As educators, we are lifelong learners. What can we learn next to help our students?”

Brantmeier, herself, has learned a lot. She and Morrow plan to produce a documentary about their collaboration at Oak Hill.

“I feel rewarded and challenged by the depth of the conversation I’ve had with the principal and the teachers,” Brantmeier said. “It has helped me better understand the issues we face in St. Louis.

“I’ve learned to tailor the findings of my laboratory research to meet the immediate demands of a local school,” she said. “To do all of this right at home, with educators who have welcomed me with open arms, has been very exciting.”