A party wall, in architectural parlance, is a structural support shared by adjoining properties. Critical building systems — electrical and plumbing; insulation, ventilation and fire suppression — are often embedded within.

Neighbors may seldom ponder those connections. But like any communal space, the party wall can become a site of collaboration or contention.

So argues Petra Kempf, an assistant professor of architecture and urban design in WashU’s Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. Over the last 2 1/2 years, Kempf has developed large-scale drawings, 3D-printed models and a forthcoming book — collectively titled “Party Wall Common-Collective Forms of Living” — that examines legal and spatial ideas about ownership, isolation and the nature of common ground.

“The party wall is often invisible,” Kempf said. “But it can be quite powerful. I want to investigate what it can teach us about collective living. How might new infrastructural connections unfold?”

Future climates

“Party Wall Common” is among a handful of WashU projects now on view in the Venice Architecture Biennale and associated exhibitions. The sprawling festival, arguably the profession’s most prestigious, includes a main exhibition and 66 national presentations, with a number of concurrent, parallel shows.

Work by Seth Denizen, an assistant professor, and Montserrat Bonvehi Rosich, a visiting assistant professor, is featured in the main survey, “Intelligens: Natural, Artificial and Collective.” Curated by Italian architect and engineer Carlo Ratti, and spanning sites in the Giardini della Biennale and the Arsenale, a former shipyard, “Intelligens” explores how architecture and urban design are adapting to new and changing environments.

“Three Landscape Essays: Mobile Ecosystems for Future Climates,” which Denizen and Rosich developed in collaboration with Spanish architects Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco and Lys Villalba, addresses the challenge of creating greenspace in dry, densely built cities. Installed in 2023 at the Conde Duque Contemporary Culture Center in Madrid, the project consists of three mobile gardens, or “islands,” each representing a specific topography.

Mounted on wheels, the islands — which incorporate a variety of water-storage techniques — can be moved across a vast courtyard while supporting arts activities that range from theater and dance to music, spoken word and the visual arts.

The Spanish Pavilion

Also located in the Giardini is the Spanish national pavilion, which includes several WashU connections.

Titled “Internalities: Architectures for Territorial Equilibrium,” the Spanish display examines the social and environmental costs associated with architectural production. It consists of a central hall and five surrounding research halls, each highlighting a related theme.

On view in the central hall are detailed models — fabricated by graduate students Lydia Roberts (MArch ’26) and Mason Burress (MArch ’25) — for “House in Arteaga,” a low-carbon residence completed in 2021 by then-faculty members Mónica Rivera and Emiliano López. Located on a gentle slope near a wide estuary, the house is raised on limestone blocks to minimize its environmental footprint. External solar protections, an HVAC heat recuperator and other efficiency measures limit electrical usage to less than 1% of U.S. and European averages.

In addition, senior lecturers Anna and Eugeni Bach designed and curated the research hall dedicated to “Labor.” Developed in collaboration with photographer Caterina Barjau, the exhibit investigates strategies for recovering local construction knowledge while de-emphasizing reliance on global technologies and supply chains.

Time Space Existence

Finally, in the historic Palazzo Mora, Palazzo Bembo and Marinaressa Gardens, is “Time Space Existence.” Organized by the European Cultural Center, this concurrent exhibit explores how architecture and design can serve as engines of social and environmental repair.

Alan Goldberg (BArch ’54), a longtime partner-in-charge at Eliot Noyes & Associates (now AG|ENA Architects), has played an important role in the development of retail hydrogen fueling. “Prototype: Advanced Hydrogen Refueling Retail Center,” aims to demonstrate hydrogen’s potential as a clean, safe and renewable energy source.

Hyrdrogen cars, also known as fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), are propelled by electricity. But where other electric vehicles rely on batteries and external chargers, FCEVs employ hydrogen fuel cells to produce their own electricity via chemical reaction. Using a radial layout in a parklike setting, Goldberg’s “station of the future” would generate that hydrogen on site, eliminating the need for transportation and storage, while integrating dispensers, lighting, fire suppression, signage and other systems into the station’s architecture.

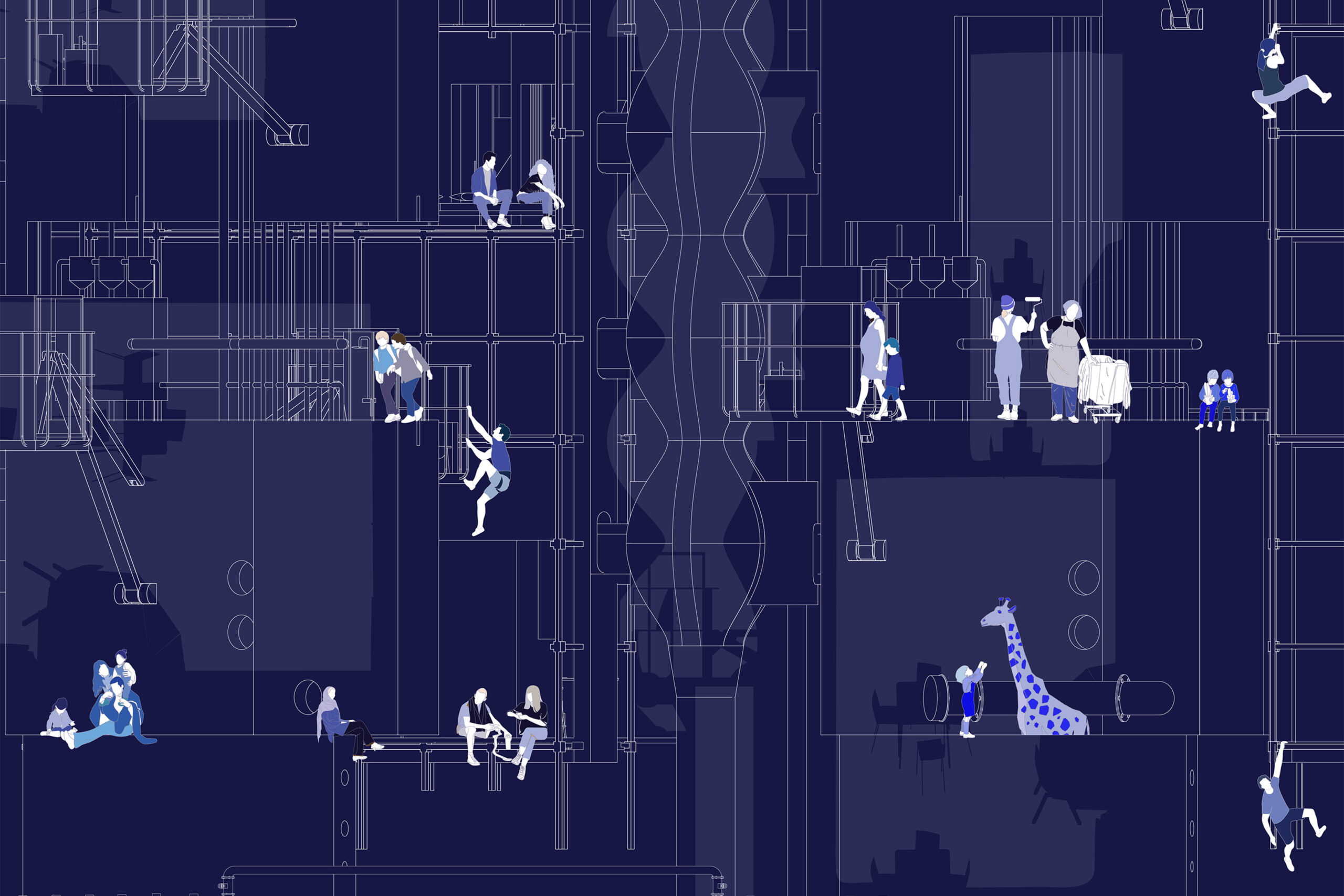

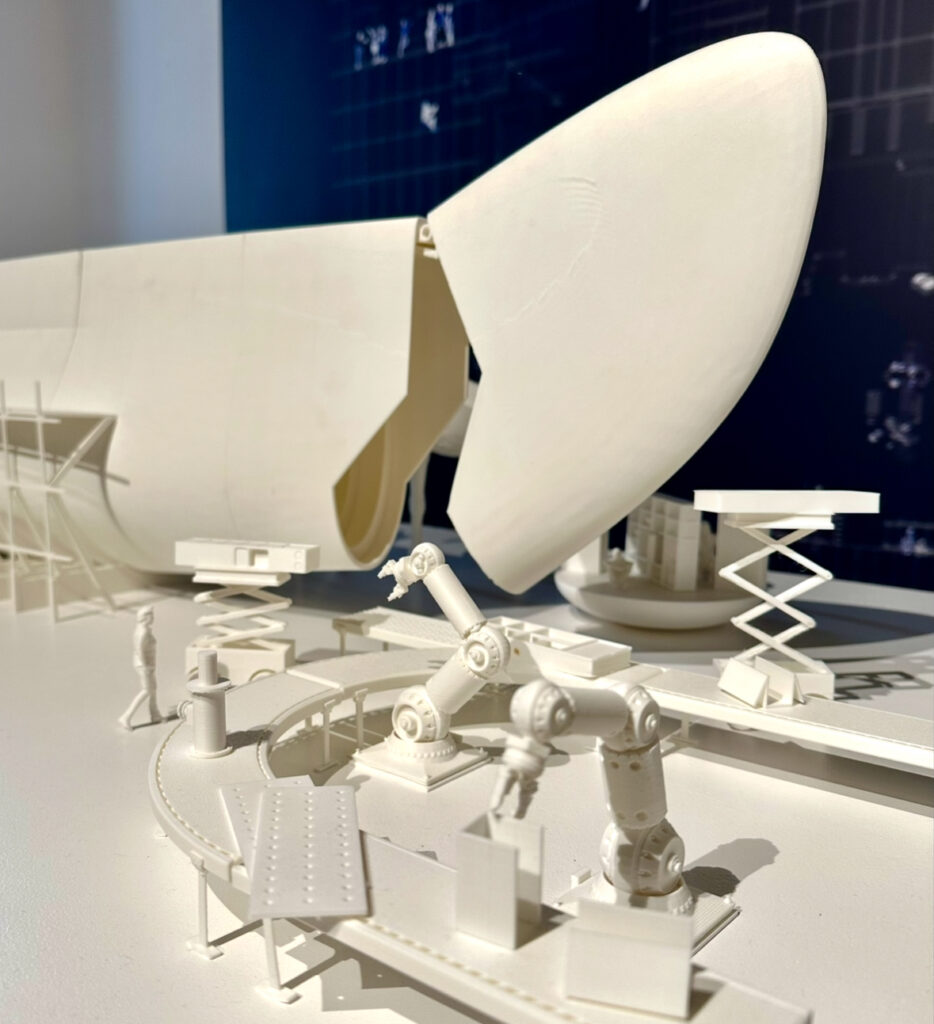

Also featured in “Time Space Existence” is Kempf’s “Party Wall Common.” Building on her project “Confronting Urbanization,” which was featured in the same show’s 2021 iteration, “Party Wall Common” investigates the row house typology, how it was shaped by legal conceptions of ownership, and how new forms of ownership might promote stewardship and care.

Kempf’s display embraces an almost playful symbolism. Umbrellas, submarines, giraffes, conveyor belts and scenes of everyday life fill a wall-sized drawing and two printed models — all created with assistance from Sam Fox School students. But if the ambition seems utopian, Kempf emphasizes that the project is fundamentally buildable.

“We have cat doors. We have dog doors. We have spaces for children,” she said. “We have water collection and regenerative forms of energy. We have hydroponic farming and rooftop greenhouses. We calculate that party wall infrastructure could feed multiple families.

“Hannah Arendt spoke of all society as sitting around a table,” Kempf continued. “It we stop talking to one another, the table disappears. ‘Party Wall Common’ is my attempt to bring people back together, through the very things that divide us.

“What would happen if I opened a door and let my neighbor in?”

The Venice Architecture Biennale opened May 10 and remains on view through Nov. 23. For more information, visit labiennale.org.