We had an immediate affection for one another, that day at lunch, and we acknowledged it, as was right and proper among the grown-ups, for one instant at farewells. I’ve remembered that moment with happiness, and will continue to do so, and as I hope you may do too. Maybe just as well – though I don’t altogether think this – that we’re in no position to get all of this translated into reality; think of the damage we’re not doing to one another!

That letter, dated Jan. 7, 1972, marked not the end, but the beginning of a secret love affair between acclaimed poet Howard Nemerov and Joan Coale of Philadelphia. Over the course of nearly two decades, Nemerov, who was on the faculty at Washington University from 1969-1991, ultimately serving as the Edward Mallinckrodt Distinguished University Professor of English and distinguished poet in residence, sent Coale 461 letters. The last one arrived in 1990, about a year before Nemerov’s death from cancer at age 71.

Those letters and accompanying materials now join the WashU Libraries’ Modern Literature Collection, which features The Howard Nemerov Papers, an expansive collection of Nemerov’s correspondences with important literary figures, drafts of poetry, recordings of readings, ephemera from appearances across the nation, and much more. Joel Minor, curator of the Modern Literature Collection and manuscripts, is studying the letters to discover what more we can learn about Nemerov, who won both the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize in 1978 and served as U.S. poet laureate from 1988-1990.

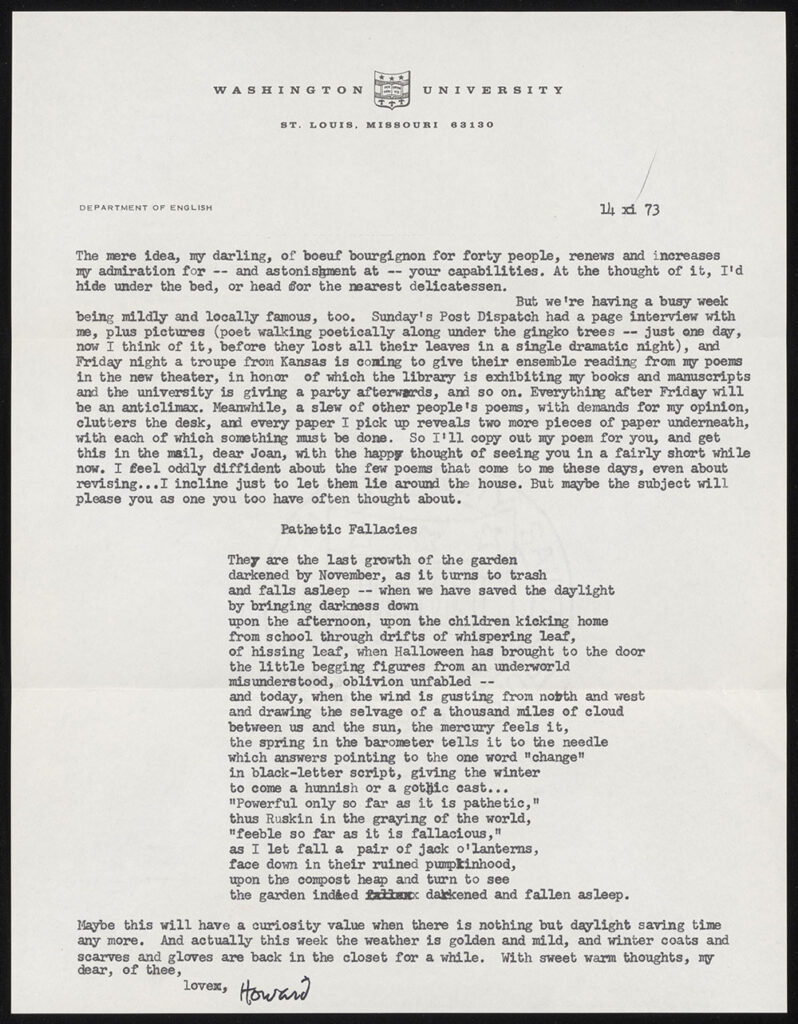

In one letter, Nemerov reflects on the photography of his famous sister, Diane Arbus: D’s work is indeed remarkable, but it does sometimes seem to be saying either pictures like these should not exist, or else people like us should not exist. Or maybe God? In another, he articulates the why of his work: I keep insisting that poetry is an attempt to speak the silence, to see invisible things and say unspeakable things about them.

Other letters contain drafts of yet-to-be published poems; observations about Dante, Proust and Shakespeare; and updates on his progress — or lack thereof — in his own writing. Coale clearly wrote Nemerov as many, if not more, letters, though only 24 exist in the Howard Nemerov Papers.

“In addition to a romantic interest in each other, there’s very much intellectual interest,” Minor says. “There were conversations going on in the letters. He was often responding to her comments about art and literature as well as personal topics such as parental concerns. He cared about her perspectives and her emotional states, and he deeply appreciated her advice and support.”

A bombshell

Minor learned of the letters this past winter after he received a surprising email from Coale’s son, coincidently named Howard. His mother, he wrote, had died at age 97 and wished for the letters to be donated to WashU upon her death.

“The relationship was a secret between them and was very well kept,” Coale wrote in the email. “Also, as my mother mentioned to me on several occasions, Howard kept his letters very discreet and as unromantic as possible, with an eye to posterity, and most importantly to protect his family.”

“That first email from Howard [Coale]— it was a bombshell,” Minor says. “This is what I mean when I tell people you never know who’s going to contact you. It’s the really exciting part of the job.”

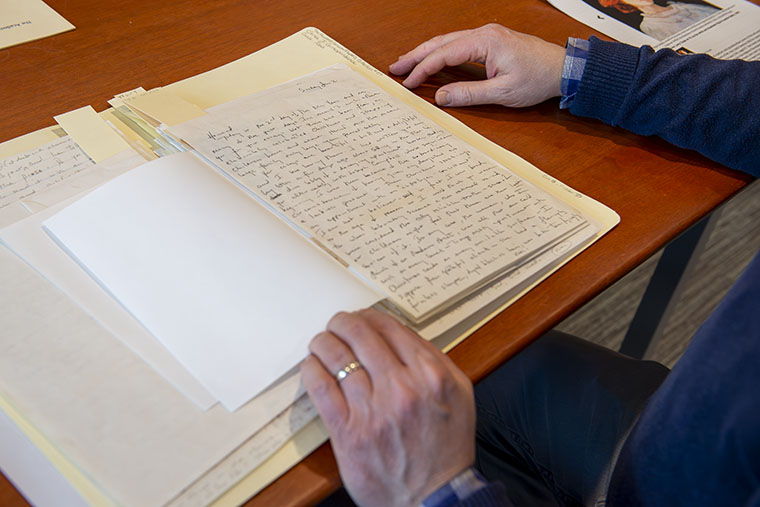

On Feb. 13, Coale flew to St. Louis to present the letters to WashU curators and scholars at Olin Library. Art historian Alex Nemerov, the Carl and Marilynn Thoma Provostial Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Stanford University and Nemerov’s middle son, also attended the ceremony.

“Well, first I have to just make sure that you are not my brother,” Nemerov quipped upon meeting Coale for the first time.

Alex Nemerov had no delusions about his father and long assumed that he had engaged in extramarital trysts when traveling to readings and conferences. He can’t say whether it is better or worse that his father betrayed his mother with one woman versus many, only that those years at home were “a mess.”

“This beautiful love affair between my dad and this woman had downstream consequences which shaped my life in a bad way,” Nemerov says. “This revelation puts things in a sharper focus, but I don’t really want to get into blame or anger. I’m trying to approach the whole thing in the tone of forgiveness and understanding.”

Alex Nemerov was truly happy to meet Howard Coale and learn more about Joan, a divorced mother of four who loved James Joyce, Johann Sebastian Bach and art. Still, he doubts his father ever intended for these letters — some of which are, indeed, romantic — to be public.

“This would not be as he wished, not even by a long shot,” Nemerov says. “My dad would have been the ultimate person to say that the backstory and his life are of no concern. It’s the poems themselves.”

And yet, the letters may bring new attention to a literary genius who could be as vain as he was private.

“My dad is not really a name anymore, not really, which is not fair and unfortunate. One doesn’t see his books in bookstores or a Library of America edition of his poetry,” Nemerov says. “For him to perhaps receive renewed attention in this way — you have to appreciate the irony of it.”

Meanwhile, scholarship continues on the Joan Coale Collection of Howard Nemerov Correspondence, which includes 461 letters and additional items such as drafts of Nemerov’s poems, clippings and invitations from Nemerov to Coale. Minor is in the process of indexing the letters and the collection is open to the public.

For his part, Alex Nemerov hasn’t read the letters yet, but he will. There was, however, one letter he did read on the flight to St. Louis to meet Coale. In it, his father tells Joan Coale that she would like Alex, that he is “such a tender spirit, despite his dour demeanor.”

“Everyone I tell that to here just laughs,” Nemerov says, “because that just seems so accurate. That really softened me in one sentence to the whole thing. That was a very tender moment for me, feeling validated and loved by my father.”

‘Poet walking poetically along under the gingko trees …’