A lot has happened in the two weeks since “Liberation Day,” the day when President Donald Trump implemented sweeping tariffs, including a universal 10% tariff on all imports and additional reciprocal tariffs on imports from certain countries.

From a global market meltdown and unprecedented trade war to a 90-day pause on tariffs for many countries, stalled trade talks with the European Union, soaring tariffs on China and exemptions that seem to change by the hour, it can be hard to keep up.

Below, John Horn, a professor of practice in economics at Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis, explains how tariff uncertainty and confusion is contributing to market volatility — and how this might impact long-term economic trends.

Why did Trump pause some temporary reciprocal tariffs last week?

I think there was a lot of pressure building up to that moment, in particular from the bond selloff and stock market. Earlier in the week, a rumor went around that tariffs were going to be paused, and that led to a huge rebound in the stock market. So that added pressure on the administration to make changes.

What is the status of tariffs currently?

It’s changing by the day. While the 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs was welcome news, that’s only one piece of the puzzle. We still have 10% universal tariffs on all goods. For context, the average tariff rate on everything we import was 2.5% — and for industrial goods it was 2% — at the end of 2024. So that’s a four to five times increase. At the same time, the tariff on Chinese products went up to 145%.

How is this impacting the economy?

I don’t think the pause in reciprocal tariffs has eased any uncertainty for investors. And that shows in the stock market fluctuation. Increased tariffs mean prices and inflation will continue to rise, leading to increased risk of a recession. The escalating trade war with China, which is the second-largest importer to the United States behind Mexico, adds to those concerns.

The other worrying trend is the bond market, which is an important indicator of the longer-term economic outlook. The bond sell-off is likely due to other countries selling off their Treasuries as a response to the tariffs, as well as other buyers getting nervous about the long-term outlook on the U.S. economy and the ability of the U.S. government to pay off those bonds (i.e., not default).

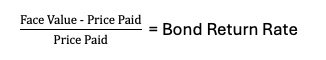

Why does this matter? For starters, bond prices follow the standard supply-and-demand framework: as demand falls, the price decreases. But that decrease in price actually leads to a higher return that investors earn. That rate is determined by taking the difference between the face value of the bond (which does not change) and the price you pay (which decreases), divided by the price you pay. The face value minus the price paid is bigger, and when you divide a bigger number by a smaller number, the result is greater.

The impact doesn’t stop there, though. When interest rates for U.S. debt increase, other interest rates also rise. If they didn’t, investors would only buy U.S. debt because it would have better yields. So now credit card interest rates, mortgages and car loan rates are also going to increase. Before long, we’re headed into a recession.

That also means that government debt rates will go up. That will impact the federal government down to individual municipalities because it will cost more to issue new debt to continue funding the government.

Last week, the Federal Reserve announced the consumer price index in March rose 2.4% on an annual basis, a lower rate than economists had expected. How does this factor into the overall economic outlook?

The inflation numbers were lower primarily in fuel and transportation services, in particular, airlines. These tend to fluctuate and will likely increase again in the summer. Inflation expectations have also been increasing, according to the University of Michigan consumer sentiment survey. If the tariffs on China remain, inflation will increase because we buy so much from China. Even if we can find an alternative supplier in other countries, the prices will still likely be higher due to extra demand for those suppliers, and because they are less efficient to begin with — otherwise, we’d be buying from them already.

What do you think the administration’s end game is? Do you think this strategy could result in better trade deals for the U.S.?

The administration’s strategy is hard to figure out because it’s not clear what the objective is. It has been reported to be a return of manufacturing to the U.S., an increase in tariff revenue, a growth in the U.S. economy, a tactic to lower tariffs from other countries, among others. But these are contradictory. If we increase tariff revenue, it means we’re still importing instead of producing in the U.S. If, instead, we do grow manufacturing, then we won’t be importing as much and therefore not generating tariff revenue. If the goal is to lower other countries’ tariff rates, then we will continue to buy from them, which doesn’t increase manufacturing or tariff revenue. And tariffs are taxes, which lead to lower economic activity.

As for the trade deals the administration has promised, forcing negotiations is generally useful only in very tactical, winner-take-all negotiations — and it’s not always true in those cases. The general guidance for negotiating is to find win-win opportunities and to create a relationship that eases the ability to negotiate over time. International trade and relationships are long-term interactions, so negotiation strategy tends to favor relationship-building and win-win seeking. It’s not clear how the administration’s tactics will lead to those outcomes.

What would you advise businesses to do during this time of economic uncertainty?

The best thing businesses should do is to shift to a more conservative investment and spending approach. No one company can rebuild the U.S. supply chain and manufacturing sector, so being on the forefront leaves you exposed by yourself to the stormy weather ahead. Unfortunately, if every company adopts this view, then no one will take the lead to rebuild the future economic systems. Typically, these are roles the government steps in to coordinate, but this administration seems to be moving in the opposite direction — reducing the scope and actions the government takes in the economy.