People interact with dimethyl ether (DME) in some form every day, most commonly through its function as a refrigerant. DME is one of those intermediary gases that can turn chemicals into different useful chemicals and turn waste into gases that serve as fuel.

Engineers at Washington University in St. Louis will be working to improve energy efficiency in production of that useful gas thanks to a $2.1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

The work, led by Xinhua Liang, a professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering at WashU’s McKelvey School of Engineering, is one of 66 projects selected to support “transformational technologies” that reduce energy demand and improve American productivity, according to the DOE.

“Dimethyl ether is one important intermediate for producing several chemicals,” Liang said, noting that DME can serve as an alternative fuel to replace diesel gas because of its desirable properties, such as high efficiency of combustion and low emissions of nitric oxide and carbon monoxide.

In addition, it can be handled with similar infrastructure that contains liquified petroleum gas.

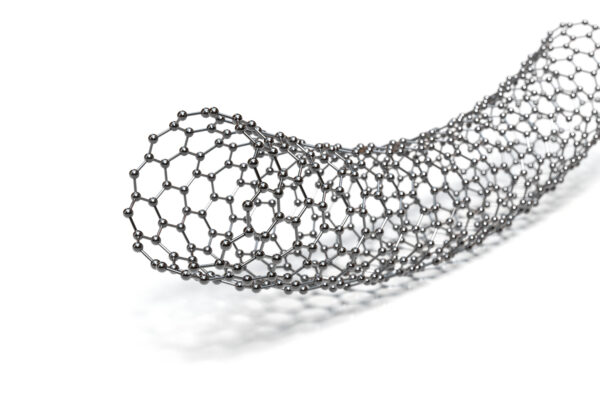

For next-generation technologies to serve as a bridge to more carbon-neutral production, the tech needs to fit the existing infrastructure, Liang said. This grant is just one of the “carbon management” projects Liang has taken on in recent years. Previously, he was awarded $2 million to research converting carbon dioxide to alternative cement, and most recently he received $1.5 million to research converting CO2 to carbon nanotubes.

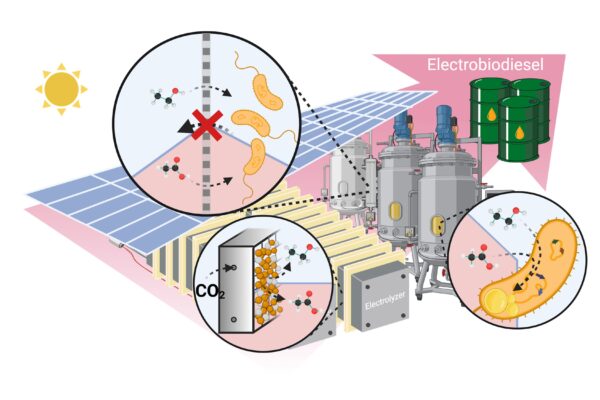

Sourcing the building blocks for DME production is its own form of waste reduction because the process starts with collecting “waste gases.” These gases are produced in bioproduction. Where there is fermenting living mass, either in the production of food or fuel, there are waste gases that can be collected and turned into something useful.

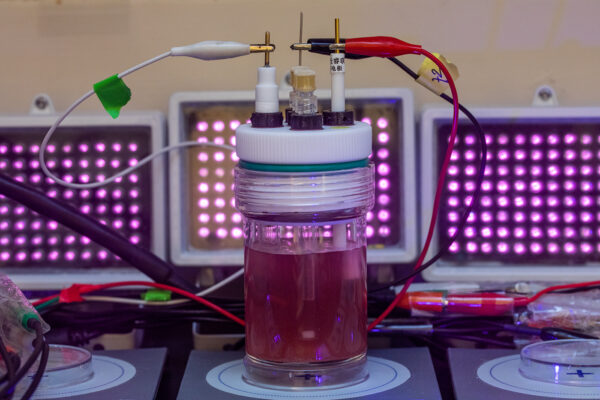

That’s where Liang’s lab comes into play, in partnership with National Renewable Energy Laboratory and BASF, the world’s largest chemical company. His task is to develop a more energy-efficient process to convert waste gases like CO2 and methane into DME.

To do this, they will use electrified induction heating but localize the heat source to only what’s necessary for the thermocatalytic process. The process will be fine tuned over the next three years.

“Our goal is to deliver one prototype system and help enable this biofuel to be more affordable to mass produce,” Liang said.