The Department of Mathematics in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis has announced the results of the 74th William Lowell Putnam Mathematics Competition.

The university fielded 19 students in the competition, held in December. More than 4,000 students from 557 colleges and universities across the United States and Canada took part.

Three students must be designated in advance as the school team, and the team score is based on the three individuals’ scores.

This year, the WUSTL team, consisting of sophomore Anthony Grebe, junior Patrick Lopatto and freshman Jongwhan Park, placed 10th out of 430 teams.

During the past 20 years, the WUSTL team has ranked among the top 10 teams seven times (and twice has made the top five).

The competition consists of two three-hour sessions during which contestants work individually on 12 problems.

“The Putnam is difficult,” said Grebe, who was on both the Putnam and the Missouri Collegiate Mathematics Competition teams this year. “The median score is usually zero or some small fraction of a problem. Even if you solve only one problem completely, you’re above average.”

“Putman problems are written by absolute masters of problem

writing,” said junior Alan Talmage, who also sat for both competitions. “The problems usually have a very clever solution built into them. There will be some method that makes the problem easy, but finding that method

will be very hard.”

Carl Bender, PhD, professor of physics and one of the Putnam coaches, gave the following example of an “easy” Putnam-style problem: Two mathematicians named A and B meet on the street. ‘I haven’t seen you for a while,’ says A. ‘How old are your three kids now?’ ‘Well,’ says B, ‘the product of their ages is 36.’ ‘Ach, tell me more,’ says A. ‘Oh, sorry,’ says B. ‘I should add that the sum of their ages is equal to the number of windows in the house over there.’ ‘I’m still at a loss.’ says A. ‘You’ve only told me two things and there are three kids.’ ‘My fault entirely,” says B. ‘I meant to tell you, the oldest is playing piano.’ ‘Oh, yes, of course, says A. Now I have it.’

And in fact you do at this point have enough information to determine logically and uniquely the ages of the three kids.

“When you first read a Putnam problem, you don’t have a clue what it is about,” Bender said. “You don’t know how many windows there are in that house, so how does that help? And what does playing piano have to do with it?”

“Normally, you spend the first hour of the competition poking

around the problems, trying to understand them, but not doing very much in the way of

computation,” Talmage said. “Then, suddenly, you see something that looks interesting and you realize, ‘Oh,

I get it, if I just do this, it will all

fall out nicely.’ ”

Both Grebe and Talmage admit that the first phase of blind probing can be nerve-wracking. It’s hard to tell whether your attempt isn’t working or if you’ve just not gotten far enough, Grebe said.

“Should you give up on a problem and work on another one, or stick with same problem in the hope that in another hour you might get somewhere?” he said.

“You get used to it,” Talmage said. “But there are moments when you realize, OK, I have no idea what I’m doing. I’m just going to stop, clear my head, and look at the problem in a completely different way.”

What he says next may sound like a non sequitur but is actually typical of the contestants.

“I absolutely love it. I love doing math. I come out of the competition completely drained and normally just go straight home and fall asleep. But I absolutely love it.”

“Solving problems like these can be very habit forming,” said Bender. At first you’re in darkness, completely lost and without a clue,” said Bender. “And then, suddenly, you see the point in a flash of inspiration. It is very rewarding.”

Elizabeth Lowell Putnam established the William Lowell Putnam Intercollegiate Memorial Fund in memory of her husband, who graduated in mathematics from Harvard University. The first competition was held in 1938, and the Mathematical Association of America has sponsored the contest since then.

Students prepare for the Putnam during Friday afternoon practice sessions in the fall semester. The coaches this year were Xiang Tang, PhD, associate professor of mathematics; Richard Rochberg, PhD, professor of mathematics; and Bender. The practices featured free pizza, paid for by the Department of Mathematics from money won by past Putnam teams. (The top team can win as much as $25,000.)

An archive of Putnam problems can be found here.

Missouri Collegiate Mathematics Competition

WUSTL math students also did well in the 19th annual Missouri Collegiate Mathematics Competition, held March 27-28 at Saint Louis University. Forty-seven teams from colleges and universities across Missouri took part.

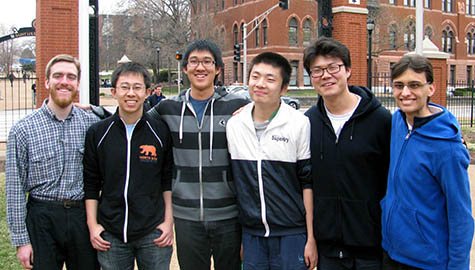

The two WUSTL teams took first and third place. A team consisting of Grebe, Talmage and sophomore Fangzhou Xiao captured first place with a perfect score of 100 — the first in the competition’s history. The second team, consisting of junior Yu Tao Li and seniors Stephen Rong and Jason Zhang, took third place, with a score of 98.

The competition consists of two sessions, during each of which teams work collaboratively on five problems for 2 1/2 hours. The Missouri section of the Mathematical Association of America sponsors it. Since it began in 1996, a WUSTL team has captured first place 12 times.

Ron Freiwald, PhD, professor of mathematics and director of undergraduate studies in mathematics, and Blake Thornton, PhD, coordinator of lower-division teaching, shepherded the students through the state competition.

To view problems from this year’s state competition, visit the competition’s website.