Huntington’s disease is a devastating, incurable disorder that results from the death of certain neurons in the brain. Its symptoms show as progressive changes in behavior and movements.

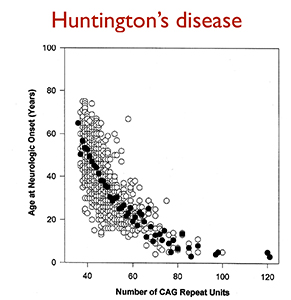

The neurodegenerative disease is caused by a defect in the huntingtin gene (Htt) that causes an abnormal expansion in a part of DNA, called a CAG codon or triplet that codes for the amino acid glutamine. A healthy version of the Htt gene has between 20 and 23 CAG triplets. The mutational expansion in Htt can lead to long repeats of the CAG triplet, resulting in the mutant protein having a long sequence of several glutamine residues called a polyglutamine tract. This CAG triplet expansion in unrelated genes is the root of at least nine neurodegenerative disorders, including Huntington’s disease.

Rohit Pappu, PhD, professor of biomedical engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues in the School of Engineering & Applied Science and in the School of Medicine, are working to understand how expanded polyglutamine tracts form the types of supramolecular structures that are presumed to be toxic to neurons — a feature that polyglutamine expansions share with proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease.

In recent work, Pappu and his research team showed that the amino acid sequences on either side of the polyglutamine tract within Htt can act as natural gatekeepers because they control the fundamental ability of polyglutamine tracts to form structures that are implicated in cellular toxicity. The results were published in PNAS Early Edition Nov. 25.

“These are progressive onset disorders,” Pappu said. “The longer the polyglutamine tract gets, the more severe the disease, and the symptoms worsen with age. Our results are exciting because it means that any success we have in mimicking the effects of naturally occurring gatekeepers would be a significant step forward. And mechanistic studies are important in this regard because they enable us to learn from nature’s own strategies.

“Previous studies from other labs showed that the toxic effects of polyglutamine expansions are tempered by the sequence contexts of polyglutamine tracts in Htt, not just the lengths of the polyglutamine tracts,” Pappu said.

He and his research team focused on understanding the effects of sequence stretches that lie on either side of the polyglutamine tract in Htt. The results show that the N-terminal stretch accelerates the formation of ordered structures that are presumed to be benign to cells, whereas the C-terminal stretch slows the overall transition into structures that are expected to create trouble for cells, suggesting that these naturally occurring sequences behave as gatekeepers.

“It appears that where polyglutamine stretches are of functional importance, nature has ensured that they are flanked by gatekeeping sequences,” Pappu said.

Pappu and his team are now working to find ways to mimic the effects of the N- and C-terminal flanking sequences from Htt. His team is working closely with Marc Diamond, MD, the David Clayson Professor of Neurology at the School of Medicine, to understand how naturally occurring proteins interact with flanking sequences and see if they can co-opt them to ameliorate the toxic functions in the polyglutamine expansions.

Crick SL, Ruff KM, Garai K, Frieden C, Pappu RV. “Unmasking the roles of N- and C-terminal flanking sequences from exon 1 of huntingtin as modulators of polyglutamine aggregation.” PNAS Early Edition, published online Nov. 25, 2013.

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (5R01NS056114).