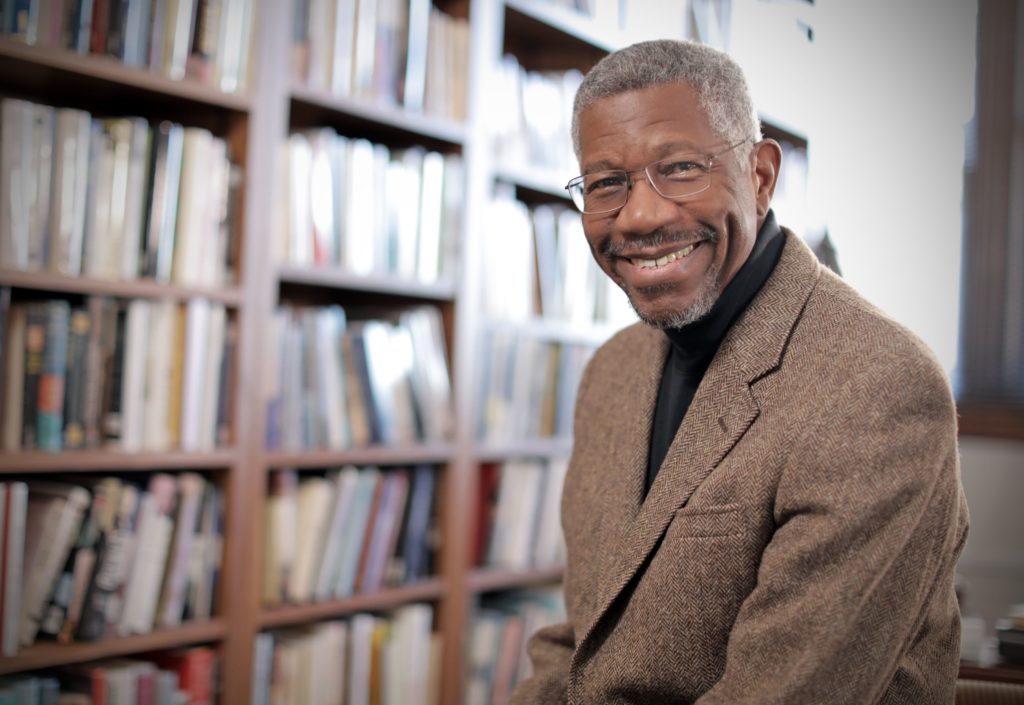

Gerald Early answered the call. It was Tom Shieber, senior curator for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, has written widely about the intersections of race and sports. Shieber explained that the Hall of Fame was preparing to update its exhibition on the Black experience.

“We talked for a while,” Early recalled. The two quickly agreed that “it was important that the exhibit not just be about Black baseball but present a Black point of view about baseball.”

Soon Early and four other curatorial consultants — authors Leslie Heaphy, Larry Lester, Rowan Ricardo Phillips and Rob Ruck — were meeting monthly in Cooperstown. “We started talking about ideas, talking about stories that we thought would be good. What was the theme for the exhibit? That sort of thing.”

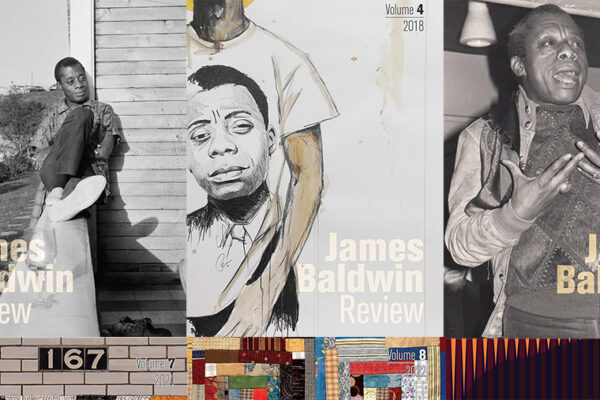

On May 25, after more than two years of work, the Hall of Fame will debut “The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball.” Beginning in the 19th century, the exhibit chronicles the formation of the Negro Leagues, the reintegration of major league play, the birth of free agency and the state of the game today.

“The story of Black baseball is a kind of social history,” said Early, noting that the title pays tribute to “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903), W.E.B. Du Bois’ groundbreaking sociological study. “The Negro Leagues were a pretty heroic effort. Even Black people who weren’t baseball fans took a certain kind of pride in showing that Black people could organize, and run a business, on this level.”

The exhibition will largely unfold through direct quotations, rather than explanatory text. “We wanted to have the people who actually played this game talking about this game,” Early said. “I read a lot of histories, a lot of player autobiographies. We were always looking for quotes!

“Of course, the Hall of Fame also has artifacts,” Early added. “There will be a lot of new technology in the exhibit, but people still want to see artifacts — a ball that Satchel Paige threw or that Jackie Robinson hit. People like to see those sorts of things.”

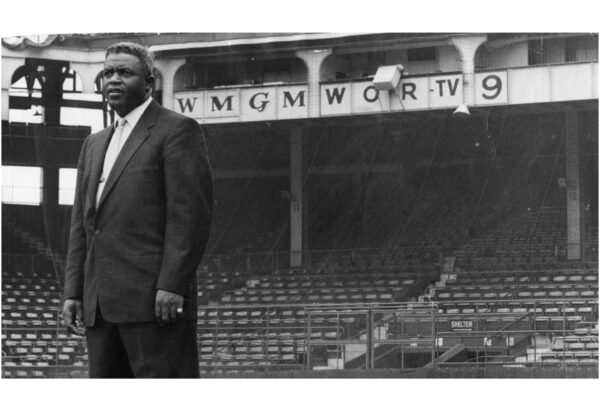

Robinson was at the center of one revealing curatorial discussion. “Most people think Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball,” said Early, who previously contributed to the collection “42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy” (2021).

But in fact, there had been instances of both Black and white players competing in the American Association, an early professional league that operated between 1882 and 1891. “So in that regard, Jackie Robinson would not have integrated baseball,” Early said. “He would have reintegrated it.”

The distinction does nothing to diminish Robinson’s singular career, his role as a champion for Black civil rights, or his sheer physical bravery. But it is a sobering reminder that not all change amounts to progress.

Other displays will highlight figures such as Andrew “Rube” Foster, a star pitcher and owner/manager of the Chicago American Giants, who in 1920 became president and treasurer of the newly formed Negro National League; and Curt Flood, the longtime St. Louis Cardinal who, in refusing a trade to Philadelphia, launched the free-agency era and helped players regain control over their careers.

In conjunction with the exhibition, Early is writing “Play Harder: The Triumph of Black Baseball in America,” forthcoming from Ten Speed Press. The book will include a narrative history of Black baseball as well as a series of spotlight essays on topics ranging from baseball and hip-hop to Black women playing in the Negro Leagues to the legacies of historian Saul White, club owner Effa Manley and players Darryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden and Michael Jordan, among many others.

I had most of my trouble in Danville, Virginia, in the Carolina league in ’56. I think that’s why I hit so many home runs that year, 51 of ‘em and 166 RBI’s. Insults pushed me to play harder.

Leon Wagner (1934-2004)

Both “Play Harder” and “The Souls of the Game” also grapple with the decline, in recent decades, of Black participation in baseball. “I felt that was an important issue,” Early said. “There is still a large Black presence in the game, but today that’s mostly through Latino players.”

Indeed, according to MLB, in 2023, roughly 6% of players were Black American, while more than 30% were Hispanic or Latino. “Some Black American players have talked about feeling isolated because they don’t speak Spanish,” Early noted. “But they also feel a certain cultural isolation — differences about music and things like that — from white players.

“So on the one hand, MLB can say, ‘We’re very integrated, we have a lot of Black people playing this game,’” Early said. “But they’re also concerned about Black Americans becoming estranged from the game.”

So how might baseball resuscitate Black interest? Early expects that MLB will continue to highlight the rich history of the Negro Leagues and other Black contributions. But at the same time, reaching younger demographics will require baseball to demonstrate contemporary relevance.

“Baseball very much glorifies its past,” Early concluded. “But nostalgia only goes so far. You have to make the game mean something to young people today.”