Black legislators talk more about race and civil rights than their white colleagues — and they often rely on powerful symbolism to connect with constituents and drive home their messages, according to new research from Washington University in St. Louis.

In an analysis of more than 790,654 U.S. House of Representatives floor speeches given between 1996-2014, researchers found that African Americans in Congress talk about civil rights over 15 times more often than white representatives. Black legislators also were more than twice as likely to invoke issue-based symbolism when discussing civil rights.

What’s more, both Black and white representatives who use symbolism in their speeches reap electoral rewards. Researchers found that symbolism is linked to an increase in Black voter turnout as well as more favorable evaluations of both Black and white members of Congress.

These findings are detailed in a forthcoming paper in the October issue of The Journal of Politics by Matthew Hayes, an associate professor of political science in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, and Bryce J. Dietrich, an associate professor of political science at Purdue University.

“Our research adds to the chorus of scholars who find that Black legislators engage in legislative behavior significantly different from their white counterparts when it comes to representing their Black constituents’ interests,” Hayes said.

Researchers were not able to access speech transcripts after 2014 because Capitol Words, a project of the Sunshine Foundation that had recorded all U.S. House floor speeches, was discontinued.

A powerful rhetorical tool

According to the authors, symbolism is important in politics because it helps speakers convey complex ideas in a way that is easier for listeners to understand and reinforces emotional attachments the audience has with the symbol.

Common examples of issue-based symbols include Martin Luther King Jr. or Rosa Parks and the Civil Rights Movement and the Stonewall uprising with LGBTQ rights. On the other side of the political aisle, critical race theory has become symbolic in recent years with conservatives’ push back against social liberalism in education, Hayes said.

‘Issue-based symbols are especially important to marginalized groups. When used appropriately, symbolic speech goes beyond empathy and conveys that the speaker is connected with the group and invested in their interests.’

Matthew Hayes

“Issue-based symbols are especially important to marginalized groups. When used appropriately, symbolic speech goes beyond empathy and conveys that the speaker is connected with the group and invested in their interests,” Hayes said.

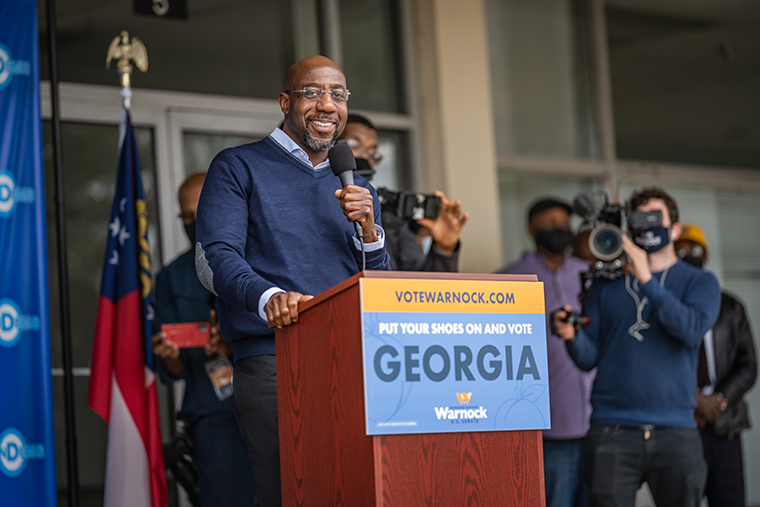

According to Hayes, representatives use floor speeches to build name recognition and garner media coverage. They’re especially important for representatives seeking reelection and serve as a means to connect with constituents and potential voters back home. As such, Hayes said he expects politicians to engage in symbolic behavior even more often when talking with constituents on the campaign trail.

How symbolic speech influences voters’ perception, behavior

In addition to analyzing 18 years of U.S. House floor speeches to understand how Black and white politicians’ use of symbolic speech differs, Hayes and Dietrich also conducted an experiment to study how constituents respond to its use. Study participants received a purported screenshot from a floor speech broadcast along with the speech transcript. They randomly varied the symbolic content, the issue — civil rights or energy — and the race of the speaker. Of the 1,031 people who participated in the study, 50% self-identified as white and 50% self-identified as African American.

The data show that Black constituents report more positive evaluations of members of Congress, Black or white, when issue-based symbols are invoked.

So why don’t more politicians use symbolic speech more often to address the Black community? One reason, the research found, could be because white politicians who misuse a symbol — such as Martin Luther King Jr. in a speech about the climate crisis — risk backlash from their Black constituents. However, the researchers found that Black representatives are not uniformly punished for misusing these symbols.

“There seems to be a degree of trust between voters and representatives that affords Black representatives the leeway to push the boundaries of what a symbol actually means,” Hayes explained.

The researchers also studied whether symbolic speech influences Black voters’ behaviors. Hayes and Dietrich turned to data from the Cooperative Election Study, a national stratified sample survey of more than 50,000 people administered by YouGov.

Indeed, they found evidence that Black voter turnout is higher in districts where members of Congress regularly invoke issue-based symbols. They also found that Black respondents are significantly more likely to vote for a white member of Congress who appropriately used symbolism when talking about civil rights in the months before an election.

Finally, they found that white politicians are more likely to use symbolic references if a significant portion of their constituents are Black. Black representatives, however, appear to use symbolism at similarly high rates regardless of their district demographics.

From civil rights to Black Lives Matter

While the study’s data ended in 2014, Hayes said he would expect the results to be even stronger today, given the movements that arose after the deaths of Michael Brown and George Floyd.

“All of our data were from before the peak of the Black Lives Matter movement, and mostly before the Shelby v. Holder decision that opened the door to states adding restrictions to voting access,” Hayes said. “As a result, I actually think we would see Black members of Congress even more active in speaking about civil rights in the contemporary U.S. Congress.

“Taken together, our research demonstrates the power of symbolism as a rhetorical tool for representatives of marginalized groups to communicate to their constituents that their concerns can and will be given a voice,” he said.