From the Civil War to the 21st century, Black women have fought to become physicians. A new book by Jasmine Brown, AB ’18, tells the story of the barriers Black women pursuing a career in medicine have faced throughout history. Published in January, Twice as Hard (Beacon Press) shines a light on the achievements of these women, often ignored or forgotten.

“It is important to understand the barriers Black women physicians faced,” Brown says. “As more professionals are working to correct some of the wrongs and increase diversity in medicine and research, we need the historical perspective to understand what these barriers are rooted in. Where are they coming from? I hoped to show some of the ways that tensional barriers contributed to what we experience today.”

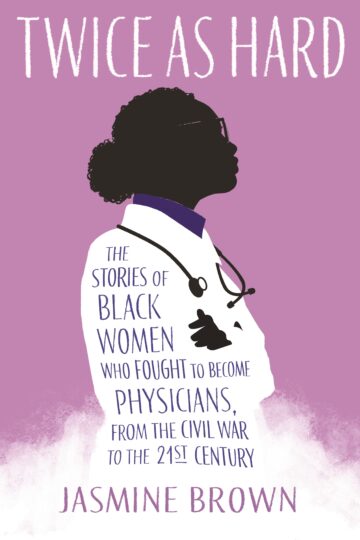

Twice as Hard

The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, from the Civil War to the 21st Century

After earning a biology degree from WashU with a focus on neuroscience, Brown, an Ervin and Rodriguez scholar, spent two years at the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar doing research on the topic that ultimately earned her a master of philosophy degree in the history of science, medicine and technology.

Brown, who is now in her third year of medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, used oral histories as her primary research method. She read transcripts and listened to audio versions of oral histories. She also interviewed practicing Black women physicians. In fact, researching the book was the first time she had met a Black woman physician — despite being a Black woman pursuing medicine.

Twice as Hard captures the historical perspective of how the medical field excluded Black people and women. At the turn of the 20th century, medicine underwent a transformation. Once thought of as a less respectable field, there was a push to make the profession prestigious and elite. The implemented changes intentionally filtered out people from the lower class or communities not viewed highly within society.

“During that time, seven medical schools dedicated to Black physicians were closed, leaving only two,” Brown says. “All of the women’s medical schools were closed.”

The message was clear: Both Black men and women were not welcome. And a bottleneck was established, making it extremely difficult for Black women to access medical education. The number of Black women physicians plummeted, and the effects are still felt today.

One story in the book tells of Rebecca Lee Crumpler, MD, the first African American woman physician, who attended medical school when slavery was still legal. She graduated a year after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed and provided medical care in Virginia to liberated Black Americans.

Another story is of May Edward Chinn, MD, who was disowned by her father for going to college and eventually medical school. Chinn worked with Peter Murray, a Black male physician, and went door-to-door caring for Black patients. They also cared for Japanese patients after Pearl Harbor — a time when other physicians refused to see them.

“I felt connected to all of them, even the women born 100 years before me who are no longer living,” Brown says. “Learning about the success they found in medicine made me feel like I could also have a significant impact as a physician — despite the obstacles I’ll likely face as a Black woman.

“I want to share those experiences with other young women, so they don’t have to journey the path to medicine without role models that look like them,” Brown says.