Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has launched its new Center for the Study of Itch, believed to be the world’s first multidisciplinary program designed solely to understand and treat itch.

The center was established to bring scientists and clinicians together to conduct research on the mechanisms that transmit itch and, ultimately, to translate those findings into better treatments for chronic sufferers.

Patients with chronic itch include those with certain types of cancer and those with liver and kidney disease. Some also may develop itching as a result of certain medical treatments or in response to pain-killing drugs. Skin diseases, such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, as well as allergic reactions, also cause itching. Antihistamines often are prescribed to treat itching caused by these latter conditions. The great majority of conditions that cause chronic itch, however, are resistant to antihistamine treatment, and some can be very debilitating.

“This center represents an important step in science’s understanding of a poorly understood phenomenon that can negatively affect quality of life for many people,” says Larry J. Shapiro, MD, executive vice chancellor for medical affairs and dean of the School of Medicine. “The new center should help speed the pace of discoveries into the basic, biological causes of itch and quickly translate them into more effective therapies.”

Historically, itch was regarded as a less intense version of pain. As a result, basic research on itching has been neglected. Only in the last few years has itch been studied as its own entity at a molecular level using mouse genetics, an approach that has long been employed to advance our understanding of numerous diseases in many other fields.

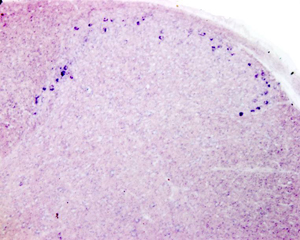

In fact, Zhou-Feng Chen, PhD, director of the new center and professor of anesthesiology, of psychiatry and of developmental biology, became interested in itch while looking for genes in the spinal cord’s pain pathway. Among the potential pain-sensing genes his team found was gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR), which turned out to be the first itch-specific receptor to be identified. Chen’s team showed that when mice were exposed to things that make them itchy, those without a GRPR gene scratched less than their normal littermates.

That led to other findings about itch and how itch signals travel along the spinal cord to the brain. Chen’s studies strongly suggest that itch and pain signals are transmitted along different pathways, so he says the time has arrived to study itch as a disease in its own right.

“There are many pain centers around the world, but we believe this will be the first center to focus on itch exclusively,” Chen says. “In fact, chronic itch is a disease of the nervous system manifested in the skin, but we understand very little about basic mechanisms and effective treatments.”

To determine whether the itch signal in different conditions is transmitted through the same pathway, the center plans to establish animal models that mimic certain aspects of human chronic itch.

The center has two primary sections: the basic research and behavioral core based in the Department of Anesthesiology; and the section on clinical research, trials and patient care. Chen, who directs the basic research section, and his colleagues work with animal models and focus on genes and molecules related to itch. Lynn A. Cornelius, MD, co-director of the center and chief of the Division of Dermatology in the Department of Medicine, will direct the clinical side. As the research progresses and better insights into the mechanisms driving itch are gained, her team ultimately will evaluate and treat patients with chronic itch.

Researchers plan to collect skin biopsies from current patients who itch to create a clinical research database and biobank, providing a unique resource for identifying genetic susceptibilities for chronic itch in humans. Cornelius and her colleagues also will conduct clinical trials of potential therapeutic agents and treatment approaches.

“Itch is not just a reflex but a unique sensation,” Cornelius says. “Similar to pain, it is likely transmitted through unique neural pathways from the skin to the brain. We envision that functional imaging will be an important part of the clinical research effort. With our colleagues in neurology, we hope to both identify specific areas of the brain that are active when a person perceives the sensation of itch. Similarly, we would use imaging to track changes in these specific areas as effective treatments are administered.”

In addition to basic and translational research, the center will provide educational training opportunities for scientists interested in studying itch. The center is hiring three full-time faculty members to initiate more studies that focus on itch, its causes and potential treatments.

Chen and Cornelius also will collaborate with faculty members from other centers, departments and divisions.

“One of our major goals is to spur translational research that can bring discoveries from the bench to the clinic,” Chen says. “That requires many different kinds of expertise, so we are very excited to be joining forces with scientists whose expertise complements our own.”

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.