Chicago has many iconic buildings, but perhaps none as instantly recognizable as Bertrand Goldberg’s Marina City. Commissioned by the Building Service Employees International Union (colloquially known as Chicago’s Janitors’ Union), and occupying a three-acre site on the north bank of the Chicago River, this pioneering mixed-use complex consists of two cylindrical 65-story residential towers as well as a saddle-shaped auditorium, a midrise office building and an open plaza with a variety of services.

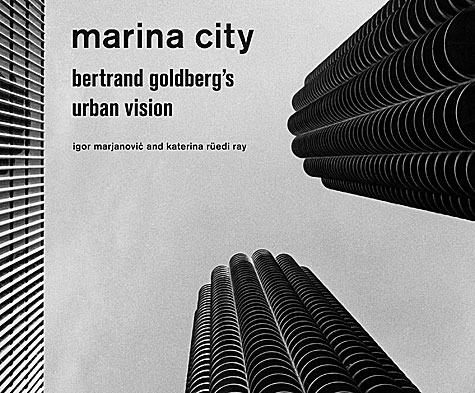

In their critically acclaimed Marina City: Bertrand Goldberg’s Urban Vision (Princeton Architectural Press, 2010), Igor Marjanović, assistant professor of architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, and Katerina Rüedi Ray, director and professor of the School of Art at Bowling Green State University, present the first book-length history — a “building biography” — of this architectural landmark.

“While this book focuses on a single building complex, it includes a broader discussion of the cultural and socio-economic contexts of architectural production — in line with Goldberg’s own passion for historical, economic, social and cultural knowledge,” the authors note in their introduction.

“Goldberg wrote about cities as cultural artifacts, blending a modernist sensibility for social action with traditional ideas of urbanism, humanism and public space,” they continue. “His ability to think across space and time was particularly evident in his integration of ideas from the European avant-garde and the U.S. market-driven building economy — a tempering of idealism with realism that led to Marina City.”

Built between 1960 and 1967, a time when many Chicagoans were fleeing to the suburbs, the project represented an ambitious attempt at urban revitalization — an attempt to create what Goldberg called “a city within a city.”

As the architect’s meticulously designed brochures detail, Marina City promised a virtually self-contained world, encompassing vast residential and commercial spaces as well as a boat marina, theater, restaurant, bowling alley, health club, ice-skating rink, grocery store, bank and other amenities. By the time of its opening, more than 2,500 applications had been submitted to rent 896 apartments.

Drawing on previously unpublished drawings, photographs and documents, Marjanović and Ray chart not only Goldberg’s architectural achievements, but also the ingenious marketing campaign and complex network of political partnerships necessary to realize what was, at the time, the largest real estate development in the Midwest.

Indeed, they argue, Marina City was ultimately the result of the combined efforts of Goldberg and two primary collaborators: William McFetridge, president of the Janitors’ Union, which largely financed the project from its pension funds; and Charles Swibel, a successful realtor who would later chair the Chicago Housing Authority. The project also engaged Mayor Richard J. Daley and President John F. Kennedy, who addressed the attendees of Marina City’s groundbreaking ceremony, hoping that it would spark a national trend of urban living.

“Even as we contextualize Marina City, we regularly return our focus to the role of the architect and his relationship to the project partners and their priorities,” Marjanović and Ray explain. Though Goldberg remains the book’s central figure, “we were also well aware of the problematic tendency of modern architectural history to elevate the architect as a hero transforming the built environment; we therefore emphasize Goldberg as part of a complex team of professional and political actors.

“Marina City introduced new ideas about form, structure, living and working, relying on innovative urban, political, financial, construction and marketing strategies to do so,” Marjanović and Ray continue. “It was a ‘house that janitors built’ – a true merger of formal and social ideals that are associated with what is often loosely called mid-century modernism.

“By examining the complex in this light we hope to illuminate broader architectural themes that speak to architecture’s potential as an agent of urban and social change.”

In the case of Marina City, the architect worked closely with his partners to reverse the exodus into the suburbs and to rally the political and public support for their vision. “They sensed or they knew or they hoped that this complex would actually change the city,” Marjanović said in a recent interview with the PBS Newshour. “In many ways it foreshadowed the later renaissance of Chicago’s downtown and the urban renewal that followed and is still continuing.”

Indeed, some testament to the longevity of Goldberg’s vision can be found in the critical and popular reception the new book has received. In addition to numerous reviews, Marjanović and Ray recently spoke to packed houses during a pair of Chicago book-launch presentations, hosted respectively by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts and the Chicago Architecture Foundation.

“While the lessons of Marina City have been well tested in Chicago, the complex was meant to provide a national precedent for an urban version of American dream,” Marjanović concludes. “It’s a vision that is gaining a new momentum as we increasingly embrace environmental sustainability, a principle that is deeply embedded in Marina City’s high density, energy efficiency and social responsibility.”