Ralph G. Dacey Jr., MD, assisted by scrub technician Tinika Noldin, uses an endoscope to examine a pituitary tumor. On the monitor: a pituitary gland.

Richard A. Chole, MD, PhD, was in his home workshop, and the sparks were flying. Chole is an ear, nose and throat specialist and surgeon. But on this day he was grinding away at a short length of stainless steel, trying to shape the hard metal into a gentle curve.

His intention was to create a surgical instrument for removing tumors near the brain.

Chole often teams up with neurosurgeons Ralph G. Dacey Jr., MD, and Michael R. Chicoine, MD, on pituitary tumor surgeries. Dacey sometimes mentioned that he would like a better surgical retractor, one that would give him a wider, clearer view of the pituitary and surrounding areas.

The two discussed what kind of instrument would fill the bill; they envisioned a retractor that would fit through a patient’s nostril and hold aside tissues to help expose the pituitary gland lying deep inside the head. Chole’s long experience with rebuilding old cars and other metalwork meant he could go to his shop and put together prototypes. Together, the two surgeons tweaked the design until they had what they considered an optimal pituitary retractor.

Chole and Dacey are good friends and joke about their respective importance in the process: “He likes to call it the Chole-Dacey pituitary retractor, but I call it the Dacey-Chole retractor,” Dacey says, smiling. There’s no argument about the quality of their invention, though. Both men say that the instrument has significant advantages over previous retractors. “We use it for most of the pituitary operations we do now,” Chole says.

Even though brain surgeons perform pituitary surgery, the pituitary gland isn’t really part of the brain. The pea-sized gland nestles in a protective bone cavity in the center of the head, directly beneath the brain. That puts it right next to critical arteries, nerves and brain regions, making pituitary surgery a very delicate operation indeed.

By far, the most common reason for pituitary surgery is to remove benign tumors called pituitary adenomas, which account for about 15 percent of brain tumors. If these grow large enough, they can cause headaches and dizziness or press on the optic nerves and lead to vision problems.

The pituitary is a hormonal jack-of-all-trades, secreting hormones that help regulate growth, blood pressure, reproductive functions, energy metabolism, fluid balance and body temperature. Pituitary adenomas can increase or decrease pituitary hormone production, leading to disorders like Cushing’s syndrome, which is characterized by weight gain, high blood pressure and other health issues, gigantism, enlarged thyroid, inappropriate milk production and many others.

During pituitary tumor surgery, doctors have to take care to avoid injury to the carotid arteries running on either side of the pituitary and to the membrane covering the brain, which is directly behind the pituitary. Damaging the healthy portions of the pituitary during surgery could harm hormone production.

The bone cradling the pituitary sits right at the back of one of the nasal sinuses. So most of the time, surgeons can reach pituitary tumors by going through these sinuses instead of opening the skull and moving aside brain tissue.

For this kind of pituitary tumor operation, Chole and Dacey divide tasks. Chole starts the procedure by cutting through or removing bone and cartilage structures within the nasal sinuses to expose the bone covering the pituitary. Then Dacey goes in to excise the tumor.

Until recently, it was routine to get to pituitary tumors through an under-the-lip, or sublabial, approach. That involves pulling up the upper lip and making incisions under it to get to the sinus cavities.

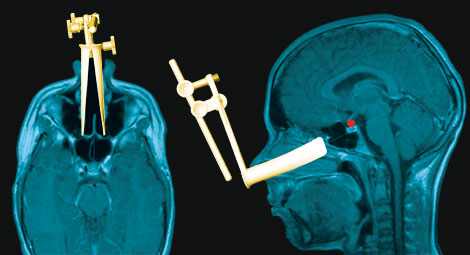

The modified retractor’s upswept curvature and subtle flaring make it easier to reach up-ward to the pituitary and push aside adjacent tissue.

Unfortunately, after such operations, patients might have lip swelling, as well as lingering numbness of the upper front teeth and lip. Sometimes patients’ dentures don’t fit well after the surgery and have to be remade. Packing the area with absorbent materials to prevent bleeding and fluid leakage often causes face and head pain during the recovery period.

To alleviate those problems, Chole and Dacey started performing the operation by entering the nasal cavity through a nostril and then going into the sinus cavities at the back of the nasal cavity. At times, neurosurgeons perform this surgery without a retractor, but many situations call for use of the instrument. Unfortunately, he found that available retractors weren’t all that practical for doing this procedure through a nostril.

The main component of pituitary retractors is something that looks like a metal tube, about three to four inches long, split lengthwise; the halves of this tube are called blades. Attached to one end of the blades at a right angle are handles that allow surgeons to manipulate the instrument and to spread the two blades apart. The blades hold tissues out of the way and give surgeons a clear pathway to insert implements for cutting

out the tumors.

“We started doing through-the-nose surgery with existing instruments,” Chole says. “But we found they didn’t angle correctly and the size was wrong. We could get by most of the time, but the view of the pituitary wasn’t as good as we wanted.”

So, in his home workshop, Chole made new blades for one of the standard retractors. These new blades had an upswept curvature at the end and a subtle flaring that made it easier for the surgeons to reach upward to the pituitary and push aside adjacent tissue. Chole also made the blades small enough to fit through a nostril.

That patched-together instrument was better, but the surgeons found a few more ways to improve the design. Working with instrument manufacturing company Anspach, Chole and Dacey have developed a final product, a stainless steel pituitary retractor with aluminum blades in three sizes suitable for children and small and large adults. The company will market the device.

Their completed retractor design is unique in allowing the blades to move in two ways: opening in parallel or opening at an acute angle. It also has a bar that rests on the patient’s forehead to stabilize the instrument.

The retractor can grip on to an endoscope, a lighted tube with a wide-angle lens. The endoscope can be fed through the retractor and back to the area of the tumor. But it also can be moved aside so it doesn’t get in the way of the surgical instruments needed to take out the tumor.

“Because the retractor can hold an endoscope, that frees a surgeon from having to hold it,” Dacey says. “The retractor also makes it easier to go back and forth between using an endoscope and using an operative microscope to see the tumor. It’s also very good that the retractor is adjustable to allow us to deal with an individual patient’s anatomy.”

Patients are likely to be pleased at the chance for pituitary surgery with fewer complications and no external stitches or scarring. Chole says one patient was surprised when he awoke from anesthesia after a recent operation.

“He felt so good,” Chole says, “that he accused us of not doing the surgery at all.”

This article appeared in the Winter 2010 issue of Washington University School of Medicine’s Outlook magazine.