A team of researchers headed by biologists at Washington University in St. Louis has sequenced the genome of a unique bacterium that manages two disparate operations — photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation — in one little cell during two distinct cycles daily.

Himadri B. Pakrasi, Ph.D., George William and Irene Koechig Professor in Arts & Sciences, spearheaded the drive to sequence the genome of Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 to understand the workings of this species’ ability to produce ethanol and hydrogen, and thus giving it the potential to become an inexpensive renewable energy source.

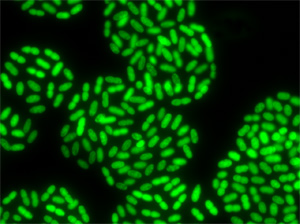

Cyanobacteria are the only known bacteria to have a circadian clock. By day, Cyanothece cells increase gene expression for photosynthesis and sugar production; at night they moonlight, ramping up gene expression that governs energy metabolism, nitrogen fixation and respiration.

Pakrasi and his collaborators found the presence of a rare linear chromosome in the organism’s genome, a first in cyanobacteria. Further examination revealed the chromosome to be 430 kilobases long and to contain a cluster of nine genes that code for enzymes involved in pyruvate metabolism, which is the basis that allows Cyanothece 51142 to produce lactate and other important compounds.

Cyanothece 51142 has one large circular chromosome, a linear chromosome and four small plasmids.

Comparative genomics

“This is the first time anything like this has been found in photosynthetic bacteria. It’s extremely rare for bacteria to have a linear chromosome,” said Pakrasi. “Nearly 100 percent of them do not. Now, we have the genome of this organism, which gives us a complete picture of everything that can possibly happen in this cell. The way the cell prospers, multiplies and dies is all decided in the genome.

“This is the benchmark, the prototype, for these cyanobacterial species. Now, we can go back to this complete picture and compare its brother and sister organisms to find their talents and deficiencies. That’s comparative genomics,” said Pakrasi.

Results were published in the on-line edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences during the week of Sept. 15, 2008. Institutions collaborating with WUSTL are the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), Saint Louis University School of Medicine and Purdue University. The project was funded by the Danforth Foundation at Washington University and the National Science Foundation, and is also part of a Membrane Biology EMSL Scientific Grand Challenge project at the W.R. Wiley Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Biological and Environmental Research program, located at PNNL. The majority of the funding for this research is through EMSL.

The researchers found that the majority of proteins on the linear chromosome are hypothetical, but the gene cluster is a major find.

“The linear chromosome contains the only gene copy for lactate dehydrogenase, which facilitates one of the organism’s fermenting capabilities, “said Jana Stöckel, Ph.D., WUSTL postdoctoral researcher who worked with Pakrasi and WUSTL postdoctoral researchers Michelle Liberton, Ph.D., and Eric Welsh, Ph.D.

“In conjunction with the proteomics group at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, we’ve been able to show that many of the genes in the linear chromosome are in fact expressing proteins, ” said Liberton. “It’s not just a piece of DNA sitting there. Transcription and translation are happening.”

Finding the workhorse

Comparative genomics is the theme for the next round of Pakrasi’s research. His laboratory has received a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy to sequence the genomes of six other Cyanothece organisms in a quest to find the best one to produce hydrogen.

“The goal is to find the hydrogen-producing workhorse of these seven, ” Pakrasi said. “Work is ongoing, and I expect in a year or so we will learn a lot more. We will be comparing functions and organizations.”

The strains, two isolated from rice paddies in Taiwan, one from a rice paddy in India, and three others from the deep ocean, are related, but each one comes from different environmental backgrounds and might metabolize differently. Thus, one or more strains might have biological gifts to offer that the others don’t, or else combining traits of the different strains could provide the most efficient form of bioenergy.

No less than four national laboratories will be involved in various stages of sequencing the other cyanobacteria: PNNL, the Joint Genome Institute (a part of Lawrence Livermore Laboratory), Oak Ridge Laboratory and Los Alamos Laboratory.

Cyanothece 51142 was sequenced at WUSTL’s Genome Sequencing Center, based in the WUSTL School of Medicine. Paper co-author Richard K. Wilson, Ph.D., Director of the Center, and Jeffrey I. Gordon, M.D., of the WUSTL Medical School’s Department of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology, had the original vision to sequence Cyanothece 51142, according to Pakrasi.

“They wanted a pilot program and brought in Danforth Foundation funding to get the project going,” Pakrasi said. “Had it not been for their vision and the initial investment, the interest and support from the national laboratories would not be what it is. More than four years ago, when we were thinking about Cyanothece, we had little idea of the organism’s potential. Today, it’s all blossomed into something much bigger than we’d thought it would.”