People who were more distressed — showing signs of anxiety or depression — during the COVID-19 pandemic were less likely to follow some best practice recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, according to a new study by Washington University in St. Louis researchers.

They found, however, that those same people were more likely than their non-distressed peers to get vaccinated. The authors refer to this as differential distress: when people act safely in one aspect while disregarding safety in another, both in response to the same psychological distress. This creates a conundrum for those trying to determine how best to communicate risks and best practices to the public.

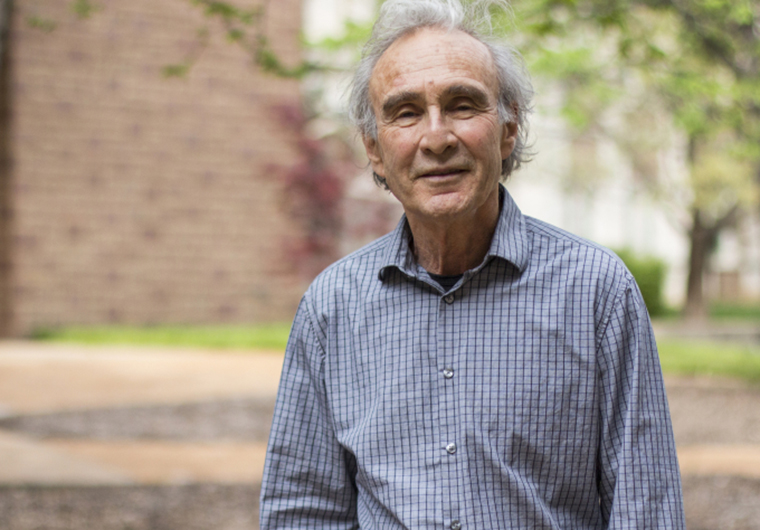

The research comes from the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences in Arts & Sciences. It was led by professors Leonard Green and Joel Myerson. The team included professors Michael Strube and Sandra Hale and Bridget Bernstein, a research technician.

Their study of 810 people revealed that distress was less likely to affect older people either way, despite their higher risk for severe outcomes if infected with SARS-CoV-2. The findings, published July 27 in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, suggest that fear messaging, which is intended to scare people and can increase their levels of distress, may not be the most effective way to encourage people to change behaviors.

“These findings do not point to a straightforward public health messaging campaign,” Myerson said. “Instead, officials may have to consider more finely tailored messages for different populations in order to achieve best outcomes: more attention to CDC recommendations as well as more people getting vaccinated.”

This is the second study from this team to analyze the ways people changed behaviors during the pandemic. The first study, published in November in the journal PLoS One, looked at social distancing and hygiene behaviors across a range of demographics. The results suggested that distress was closely tied to the way people responded to recommendations about social distancing. People who were more distressed were less likely to observe social distancing recommendations, perhaps as a way to maintain social connections that can ease anxiety and depression.

In the latest work, researchers again asked people about their adherence to the latest CDC recommendations, including newer recommendations outlining when to wear a mask and suggesting that people avoid spending lots of time inside with others. The results showed similar correlations to the previous study among age, distress and behavior changes.

In terms of public health and effective messaging, one of the most pressing issues to arise after publication of the first study was the introduction of vaccines — and the myriad ways people felt about them. Looking at four categories — fully vaccinated; partially vaccinated; unvaccinated but likely to get one; unvaccinated and unlikely to get one — several findings stood out:

- People who had been fully vaccinated were more likely than those who were partially vaccinated to have close interactions with others following their shots.

- Relative to those who said they were unlikely to get vaccinated, those who said they were likely to do so thought their chance of infection was higher.

- Depending on the person’s age, they responded differently to the same level of stress. Overall, for example, the higher level of distress someone had, the less likely they were to social distance, but the more likely they were to get vaccinated. Both of these correlations became weaker, however, as people aged.

Fear messaging that tries to scare people into following guidelines tends to be useful only for a one-time event, Green said. “Ostensibly, getting vaccinated should count as such an event.” But as breakthrough cases increase and boosters add up, vaccinations are no longer one and done; they are instead a series of events, spread out over more than a year.

Although fear-based messaging may encourage younger people to get vaccinated, it also diminishes their resolve to stick to mitigation behaviors like social distancing. Without doing both, the risk of breakthrough infections could continue to rise.

And, the research shows, messaging becomes less effective as people age — and become more susceptible to severe illness if they’re infected.

“Part of the solution to the problem of differential distress may be to avoid the distress altogether,” Green said, by forgoing the fear campaign. Instead, a gentler approach may be warranted. “Our previous work suggests that what really motivates many people to change behaviors for the better is considering how their actions can benefit, or harm, other people.”

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number RO1AG058885.