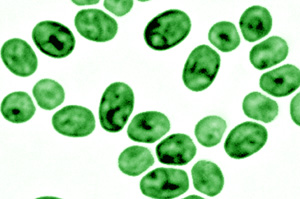

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have gained the first detailed insight into the way circadian rhythms govern global gene expression in Cyanothece, a type of cyanobacterium (blue-green algae) known to cycle between photosynthesis during the day and nitrogen fixation at night.

In general, this study shows that during the day, Cyanothece increases expression of genes governing photosynthesis and sugar production, as expected. At night, however, Cyanothece ramps up the expression of genes governing a surprising number of vital processes, including energy metabolism, nitrogen fixation, respiration, the translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) to proteins and the folding of these proteins into proper configurations.

The findings have implications for energy production and storage of clean, alternative biofuels.

The study was published in the April online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy in the context of a Biology Grand Challenge project administered by the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Bacterial biological clock

“One of the mysteries in cellular physiology is this business of rhythm,” said Himadri Pakrasi, Ph.D., the George William and Irene Koechig Freiberg Professor in Arts & Sciences and lead investigator of this project. “Circadian rhythm controls many physiological processes in higher organisms, including plants and people. Cyanothece are of great interest because, even though one cell lives less than a day, dividing every 10 to 14 hours, together they have a biological clock telling them when to do what over a 24-hour period. In fact, cyanobacteria are the only bacteria known to have a circadian behavior.”

Why does such a short-lived, single-celled organism care what time it is? The answer, according to this study, is that the day-night cycle has a tremendous impact on the cell’s physiology, cycling on and off many vital metabolic processes, not just the obvious ones.

Among the obvious cycling processes are photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation. It is difficult for one cell to perform these two functions because the processes are at odds with one another. Fixing nitrogen requires nitrogenase, a catalyst that helps the chemical reaction move forward. Unhelpfully, the oxygen produced by photosynthesis degrades nitrogenase, making nitrogen fixation difficult or impossible in photosynthetic organisms.

Other filamentous cyanobacteria perform photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation in different, separate cells. As a single-celled bacterium, however, Cyanothece cannot separate these antagonistic processes in space. But it can separate them in time.

Agreeing with previous studies, this study found that Cyanothece genes for photosynthesis turn on during the day and genes for nitrogen fixation turn on at night. The surprise is the tremendous impact the day-night cycle has on the overall physiology of the cell.

“It goes far beyond just the aspects of nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis,” said Pakrasi, who also directs Washington University’s International Center for Advanced Renewable Energy and Sustainability (I-CARES) to encourage and coordinate university-wide and external collaborative research in the areas of renewable energy and sustainability — including biofuels, carbon dioxide mitigation and coal-related issues. The university will invest more than $55 million in the initiative.

Cyanothece‘s ‘Dark Period’

To see the effect of day-night cycles on the overall physiology of Cyanothece, lead author Jana Stöckel, Ph.D., Washington University post-doctoral researcher, and other members of this research team examined the expression of 5,000 genes, measuring the amount of messenger RNA for each gene in alternating dark and light periods over 48 hours. At a given time, the mRNA levels indicated what the cells were doing. For example, when the researchers identified high levels of many mRNAs encoding various protein components of the nitrogenase enzyme, they knew that the cells were fixing nitrogen at that time, in this case, during the dark periods.

Of the 5,000 genes studied, nearly 30 percent cycled on and off with changing light and dark periods. These particular genes, the study found, also govern major metabolic processes. Therefore, the cycling of mRNA transcription, Pakrasi said, “provides deep insight into the physiological behavior of the organism — day and night.”

During the day, Cyanothece busies itself with photosynthesis. Using energy from sunlight, carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and water, Cyanothece produces glucose, a sugar it stores in glycogen granules, filling its chemical gas tank. At night, the Cyanothece ramps up production of nitrogenase to fix nitrogen, as expected. Since nitrogen fixation requires a lot of energy, Cyanothece uses the glycogen stored through a process called respiration. Because respiration requires oxygen, the cells conveniently use up this by-product of photosynthesis, likely helping to protect nitrogenase from degradation.

Through this cyclic expression of genes, Cyanothece is essentially a living battery, storing energy from the sun for later use. This feat continues to elude scientists searching for ways to harness sunlight and produce energy on a large scale. With this in mind, a new project for the Pakrasi team seeks to use the machinery of Cyanothece — its energy storage strategy, its anaerobic conditions that protect important enzymes — as a biofactory to produce hydrogen from sunlight, the ultimate clean energy source.