One of the most common human parasites, Toxoplasma gondii, uses a hormone lifted from the plant world to decide when to increase its numbers and when to remain dormant, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found.

The scientists report this week in Nature that they successfully blocked production of the molecule, known as abscisic acid (ABA), with a plant herbicide. Low doses of the herbicide prevented fatal T. gondii infection in mice.

“As a target for drug development, this pathway is very attractive for several reasons,” says author L. David Sibley, Ph.D., professor of molecular microbiology. “For example, because of its many roles in plant biology, we already have several inhibitors for it. Also, the plant-like nature of the target decreases the chances that blocking it with a drug will have significant negative side effects in human patients.”

T. gondii‘s relatives include the parasites that cause malaria, which also appear to have genes for ABA synthesis. The new findings may explain an earlier study where a group of researchers found that the same herbicide inhibits malaria.

Infection with T. gondii, or toxoplasmosis, is perhaps most familiar to the general public from the recommendation that pregnant women avoid changing cat litter. Cats are commonly infected with the parasite, as are some livestock and wildlife. Humans can also become infected by eating undercooked meat or by drinking water contaminated with spores shed by cats.

Epidemiologists estimate that as many as one in every four humans is infected with T. gondii. Infections are typically asymptomatic, only causing serious disease in patients with weakened immune systems. In some rare cases, though, infection in patients with healthy immune systems leads to serious eye or central nervous system disease, or congenital defects in the fetuses of pregnant women.

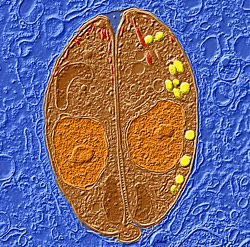

Scientists have known for approximately a decade that protozoan parasites like T. gondii and those that cause malaria contain many plant-like pathways, or groups of genes or proteins put to use for a particular biological task. The common ancestor of these parasites incorporated an algal cell millions of years ago. This endosymbiotic relationship results in the incorporated organism becoming a regular part of the larger organism’s cell structure. The parasites can make use of the algae’s genes, many of which were transferred to the parasite’s nucleus to control processes in a structure that is a remnant of the original algal cells.

That earlier revelation led to ongoing efforts to develop drugs that block plant-like proteins parasites use to synthesize metabolically important structures or compounds. However, until this study, no one had found the parasites using a plant-like protein for signaling purposes.

“Signals are sometimes even better targets for drug development than biosynthetic pathways,” says Sibley. “Taking out a biosynthetic pathway means you take away one thing from the parasite. But if you can successfully disable a key signal, this may potentially disrupt many more aspects of the parasite’s metabolism.”

Kisaburo Nagamune, Ph.D., formerly a postdoctoral fellow in Sibley’s laboratory, found the ABA pathway in T. gondii while searching the parasite’s genome for pathways linked to calcium signalling. Researchers knew that calcium signaling was important to the parasite’s ability to control its complex reproductive cycle, but a search for genes similar to the calcium signaling pathways found in mammalian cells, such as the calcium receptors or channels that are common in heart cells and neurons, found few analogs in T. gondii.

ABA has many prominent roles in plant biology, including regulation of flowering and seed dormancy. A series of experiments led by Nagamune, now an assistant professor at Tsukuba University in Japan, showed that ABA helps the parasites control their reproductive cycle by communicating with each other in the host cell. When they sense high enough levels of ABA, the parasites break out of host cells; otherwise, they stay in the host cell and remain dormant.

With help of online databases and botanists at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center in St. Louis and elsewhere, researchers quickly identified a class of herbicides that block ABA production and that are already in use commercially and screened for low toxicity to animals.

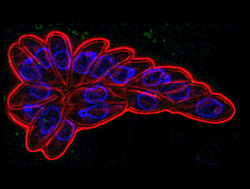

Scientists tested one of those herbicides against toxoplasmosis, labeling the test parasites with the firefly luciferase protein. Whole animal imaging showed that treatment with the herbicide reduced the number of parasites in infected mice during the initial infection and also reduced the chronic burden.

Sibley plans further studies to learn what other aspects of T. gondii biology are controlled by ABA and whether other inhibitors of ABA might make more potent treatments for toxoplasmosis. Nagamune is exploring the new findings’ implications for treatment of malaria.

Nagamune K, Hicks LM, Fux B, Brossier F, Chini EN, Sible LD. Abscisic acid controls calcium-dependent egress and development in Toxoplasma gondii. Nature, January 9, 2008.

Funding from the Uehara Medical Foundation, the Mayo Clinic, the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.