Over the past year, school districts in 26 states have banned more than 1,100 books, according to a report by PEN America. At the same time, state legislators have introduced educational gag order bills to restrict teachers’ speech. At least 12 of these proposals have become law in 10 states.

Against this backdrop, students in the “Gender and Education” spring course at Washington University in St. Louis are examining issues surrounding gender and sexuality in education — issues like representation in curriculum, experiences of LGBTQ students and teachers and disciplinary policies ranging from dress codes to Title IX compliance.

“In many ways, these are perennial issues in education,” said course instructor Lisa Gilbert, a lecturer in education in Arts & Sciences. “However, they’ve taken on increased urgency given the political activism on both sides of the issue in our current moment.”

Students say the course has been eye opening.

“Studying efforts to ban books has helped me better understand the historical, cultural and racial contexts that undergird these efforts,” said Ranen Miao, a junior majoring in political science and sociology, both in Arts & Sciences.

“One of my biggest takeaways from the project regarding banned books is how politicized school curriculums are,” said Rebecca Daniel, a senior majoring in psychology in Arts & Sciences. “Before this class, I had given some thought to the curriculum — what is included and what is excluded — but I had not really thought about the degree of representation in curricula and who determines what to include and exclude in curricula.”

Lessons in empathy, acceptance, self-confidence

“Books provide both windows and mirrors for students,” Gilbert said. “Whether we get the chance to see into another person’s experience, or we find our own experiences reflected in a story, we are learning about empathy and self-confidence.”

“That means that books like these are good for all of us, whether we personally identify with the main characters or not. Ultimately, it’s about learning to better understand ourselves and each other so that we can work together to build a better society.”

There are also lessons to be learned in what books are challenged in the first place. The majority of contested books are by or about people of color and/or LGBTQ persons, according to the American Library Association, which tracks challenges to books in public libraries and schools.

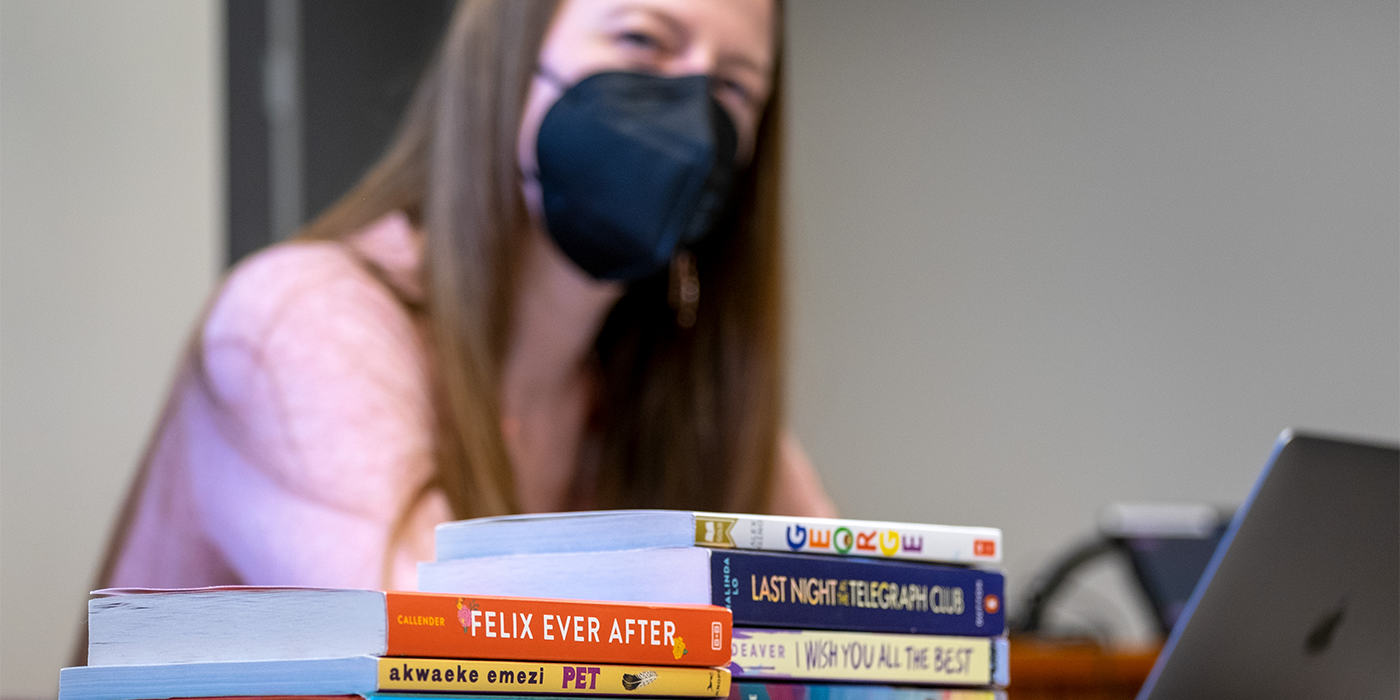

In addition to scholarly papers and news articles, students in the “Gender and Education” course formed book clubs and read a novel of their choice — books such as “Cemetery Boys” by Aiden Thomas, “Melissa” (formerly published as “George”) by Alex Gino and “Last Night at the Telegraph Club”by Malinda Lo, all of which have been the subject of challenges in public schools and libraries across the U.S.

According to Gilbert, reading banned books provided an opportunity for students to reflect on their own gender-related educational experiences and debate the value of literature in K-12 education.

“Our students come out of high schools where the traditional canon of literature they’ve typically encountered often represents only a small slice of the human experience,” Gilbert said. “So, having the chance in college to read and deeply discuss books that give a broader view of the world ultimately serves as a ballast to what they probably experienced in high school.”

That was the experience of Emily Tack, a junior majoring in psychology and women, gender and sexuality studies, both in Arts & Sciences, who said her high school prided itself for its commitment to diversity and inclusion. That commitment was not reflected in the curriculum, though.

“Having worked on this project, I’ve gained greater insight into how identities can receive representation in schools through books, yet the audiences they are meant to reach are often prohibited from learning about them,” Tack said.

“I have definitely learned that being able to see one’s own identity represented in the curriculum is critical to feeling comfortable and welcomed in the space, and books provide an important medium for providing students with such representation.”

These are lessons the students say they will carry with them long after the semester ends.

“This book (“Last Night at the Telegraph Club”) moved me on a deep level to not only reaffirm and continue pursuing my goals as an educator to provide a safe and accepting space for my students to explore their own identities, but to also accept myself as I am, despite what others may think,” said Caeden Polster, a junior majoring in education.

To concerned parents who may worry that reading controversial books will indoctrinate their children, Jasmine Stone, a sophomore majoring in education and English literature, offered the following explanation as to why children need to read books with a variety of representation:

“Even if their children are not people of color, nonbinary or any member of the LGBTQ+ community, many people they interact with and care for are or will be, and it is important for them to have the information for how to meaningfully engage in these relationships, conversations, etc.,” Stone said.