An anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis and two of his graduate students were part of an international team of researchers that discovered new fossils in the highlands of Ethiopia that are filling gaps in scientists’ understanding of the evolution of African mammals.

The researchers discovered the fossils in the Chilga region of northwestern Ethiopia. The team includes scientists from several U.S. universities in addition to Washington University, including The University of Texas at Austin and the University of Michigan, as well as Ethiopia’s Addis Ababa University and National Museum.

“The period from about 24 million years ago back to 32 million years has long stood as one of the most poorly known for all of Africa and Arabia,” said John Kappelman, project leader and a professor of anthropology at The University of Texas at Austin. “These are the ‘missing years’ for Afro-Arabia and what, exactly, happened to the mammals during this eight-million-year period of time has long remained a mystery to science.”

|

Tab Rasmussen, WUSTL professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, and two of his graduate students were part of an international team of researchers that discovered new fossils from the highlands of Ethiopia. The fossils fill a long-standing gap in scientists’ understanding of the evolution of African mammals. The team’s findings are reported in this week’s issue of the journal Nature. He offers the comments below to explain his and his students’ role in the discovery of the fossils. My role is to identify and analyze the fossil mammals, and to participate in the fieldwork. Much of my previous research is from a 32-million-year-old mammalian fauna from Fayum, Egypt (referred to in the paper as the “Fayumian” fauna). Up to the discoveries at Chilga, the Fayum was one of our only windows into the archaic mammalian faunas of Africa. These early African animals are very unusual, and unlike other mammals evolving elsewhere in the world. So, once John Kappelman found the Chilga fossils, he brought me in as a specialist, along with William Sanders of the University of Michigan, to work on the taxonomy and biological interpretations of the fossil mammals. Kappelman put together an outstanding group of collaborators, including, specialists in radiometric and paleomagnetic dating, paleobotanists and archaeologists. After the initial discovery of the Chilga fossils, Kappelman and I planned a few subsequent expeditions to Chilga. These involve setting up a fieldcamp for several weeks, with tents, a cook, and support staff, while we prospect for and collect fossils. The longest of our field seasons was from late December 2001 through late February of 2002, when I had a sabbatical leave from my teaching responsibilities at Washington University. After completing that field season, I traveled to the National Museums of Kenya and Egypt to do comparative work with fossils in the collections there. In the future, we will continue to collect fossils at Chilga, but the emphasis there will probably move in the direction of paleobotany. The fossil plants we have found at Chilga, which are being studied by Dr. Bonnie Jacobs of Southern Methodist University, represent one of the best fossil floras ever found in Africa. The plant fossils will be very important in understanding environments and climatic change in Africa. We will also explore other promising areas that are geologically similar to Chilga in the hopes of finding new fossil-producing regions. Two graduate students at Washington University participated in the fieldwork at Chilga. They are Kathleen Muldoon, a graduate student in anthropology, and Lisa Hildebrand, who just completed her Ph.D. in anthropology last month. Kathleen is interested in the evolution of African primates and other mammals. She participated in the field work at Chilga during the winter of 2001-02. Field work involves prospecting for fossil-bearing strata and collecting fossils from the strata by excavation, screening or surface collecting. Back in camp, the fossils are curated and certain data, such as measurements, are obtained. Then the fossils are molded so that casts can be made at the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa. As foreign researchers, we can carry a cast of each specimen out of the country, but the originals, of course, stay in the museum. Kathleen also spent a couple of weeks at the museum in Addis, helping to clean, curate and organize the fossil collections. She then traveled with me to Egypt and helped with the comparative studies of the Chilga and Fayum mammals. Our team’s first announcement of the Chilga fauna was made by Kathleen at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meetings in Oklahoma City in the fall of 2003. Subsequently, Kathleen has begun her own dissertation work on the unique mammal faunas of Madagascar. Lisa, who participated in the Chilga fieldwork in January 2003, is an expert in Ethiopian prehistory, with special emphasis on the domestication of endemic Ethiopian plants. Her role on the Chilga project was as an expert on fieldwork in Ethiopia, especially archaeology. She speaks Amharic, the local language in the region of Chilga. |

Several of the newly discovered fossil mammals record the earliest evidence for some of today’s favorite Africa mammals, while others represent the last holdouts of species that were thought to be long extinct. The team was astounded to find several species of primitive proboscideans — very distant cousins of today’s elephants. Even more surprising than the fact that these primitive proboscideans managed to survive the “missing years,” is that they were found to be living side by side with more advanced species that are the ancestors of today’s elephants.

“The story of early elephant evolution is one that we have long suspected to have occurred entirely in Africa,” said William Sanders of the University of Michigan. “These new fossils provide the evidence that we needed to lock down this story. These ancestral elephants were much smaller than today’s African elephants, but at nearly 1,000 kg — about that of a medium-sized Texan longhorn — they were still a bit too big to keep in your backyard.”

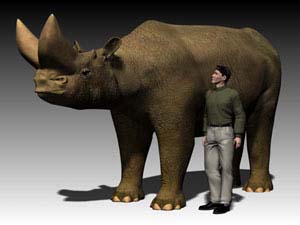

Some of the other fossil mammals are even more bizarre. Perhaps the most unusual of these is the arsinoithere, an animal larger than today’s rhino with a pair of massive bony horns on its snout. This species is also a hold over from much earlier times, but the new discoveries show that it too survived through the period of the missing years.

“If this animal was still alive today it would be the central attraction at the zoo,” said Tab Rasmussen, a professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University. Rasmussen participated in the field work and identified and analyzed the fossil mammals.

Two of his graduates students also participated in the field work at Chilga. They are Kathleen Muldoon, a graduate student in Washington University’s Department of Anthropology who is interested in the evolution of African primates and other mammals, and Lisa Hildebrand, who just completed her doctorate in anthropology from the university last month. Hildebrand is an expert in Ethiopian prehistory, with special emphasis on the domestication of endemic Ethiopian plants. She also speaks Amharic, the local language in the region of Chilga.

Unlike other paleontological fieldwork centered in much younger rocks in the fossil-rich Rift Valley of Ethiopia, this project is based in the highlands of the northwestern part of the country. This rugged terrain sits at about 2,000 meters in elevation and consists of massive flows of basalt lava that poured out of the Earth at about 30 million years ago. The sediments that contain the fossils were deposited on top of these basalts and are now exposed among agricultural fields in stream and gully cuts.

“Geologists have known about the sediments in this region for nearly 100 years because they contain abundant lignite deposits,” said Mulugeta Feseha of Addis Ababa University. “It wasn’t until we began our study that fossil mammals were discovered.”

The international team relied on high-resolution satellite imagery to find sedimentary rocks far from the nearest roads and then recorded the position of the fossils with GPS technology. The ages of the volcanic and sedimentary rocks were studied by Peter Copeland of the University of Houston and Feseha and yielded dates of 27 million years of age.

During this time period, today’s Red Sea had not yet begun to rift open and Africa and Arabia were still joined together as a single continent that was isolated from the other landmasses by surrounding oceans and seas.

The new discoveries from Ethiopia show that mammals of Afro-Arabia continued to evolve and produce new species on this isolated continent during the missing years, but the clock was ticking for many of the more primitive forms.

“At about 24 million years ago the continent of Afro-Arabian began to dock with Europe and Asia,” Kappelman said. “We believe that this event set into motion both the eventual extinction of the more primitive species as well as the modernization of the rest of the African fauna brought about by an influx of new species.”

The arsinoitheres and more primitive proboscideans became extinct, perhaps being out competed by the invading species, while the ancestors of today’s elephants flourished in spite of the new immigrants and managed to carry their adaptations out of Afro-Arabia to successfully colonize the rest of the world.

“More fossil localities closer in age to this major event are needed for us to be able to fully evaluate the competing hypotheses,” said Kappelman, “and we are convinced that the fossils are out there waiting to be found.”

“The work of this team continues to reveal the extremely rich fossil record encased in East Africa’s rocks,” said Rich Lane, program director in the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Division of Earth Sciences. “It also sheds light on the role that pre-modern animals played in establishing the worldwide distribution of mammals today.”

The results of this research are reported in this week’s issue of the journal Nature. The project is supported by the NSF, the National Geographic Society, the Leakey Foundation and the Ethiopian Ministry of Culture. The team intends to continue its fieldwork in winter 2004.