Advances in neurosurgery have opened the operating room door for an amazing array of highly invasive forms of brain surgery, but doctors and patients still face an incredibly important decision – whether to operate when life-saving surgery could irrevocably damage a patient’s ability to speak, read or even comprehend a simple conversation.

Now, researchers at Washington University in St. Louis are developing a painless, non-invasive imaging technique that surgeons here already are using to better evaluate brain surgery risks and to more precisely guide operations so that damage to sensitive language areas is avoided.

The breakthrough holds the promise of safer surgeries for the nearly 200,000 Americans diagnosed with brain tumors each year. It also may significantly improve odds of success in an increasingly common epilepsy surgery in which large damaged sections of a patient’s temporal brain lobe are removed in an effort to alleviate severe seizures.

The Washington University mapping technique, which captures functional magnetic resonance images (fMRI) of the brain as patients performs simple language functions, has the potential to replace or improve upon two much more invasive and dangerous brain mapping techniques, both of which are now commonly used before or during most brain surgeries.

In a forthcoming article in the journal Epilepsy & Behavior, a Washington University research team presents a recent brain surgery case in which their fMRI brain mapping technique helped pinpoint the unusual location of language centers in a patient with a long history of severe epileptic seizures, including information critical to the surgery’s success.

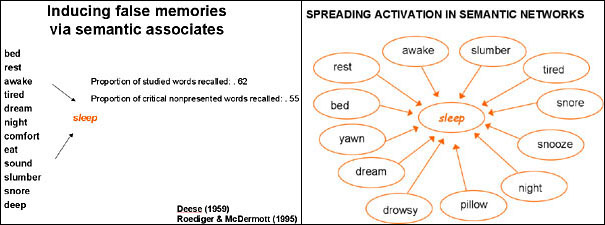

Other research has utilized fMRI testing to define language areas in the brain, but the Washington University technique has proven to be especially effective due to the integration of a “false memory” word processing test that asks patients to remember a list of rapidly presented words with related meanings or similar rhyming patterns.

“These word processing tasks were chosen because direct comparisons of meaning and rhyme processing have been shown to elicit robust activation in two distinct regions of the brain, each of which are critical to language function, “said study co-author Kathleen McDermott, an assistant professor of psychology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.

During the fMRI test, patients are provided with a list of logically related words, such as doze, pillow, rest and dream, and later asked if a non-presented but related word, such as sleep, had been part of the presented list. Most falsely recall that the word sleep had been part of the original list. Another version of the test asks patients to recall if a particular word was presented among a list of closely rhyming words.

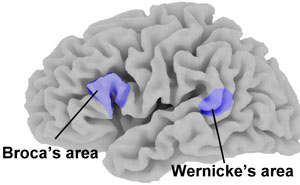

Use of both the rhyming and meaning-related lists is important because studies show the brain typically relies on separate and distinct regions to process each of these tasks. Specifically, the processing of word meanings activates a brain region known as Wernicke’s area, while the processing of word rhymes activates another important language center known as Broca’s area, McDermott said,

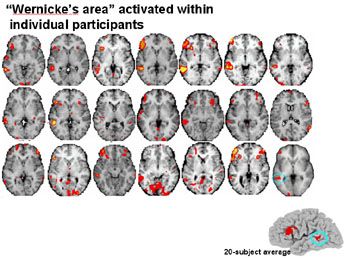

McDermott and colleagues at Washington University have spent nearly a decade using similar lists of related words to study false memories, a phenomenon in which normal cognitive processes cause people to remember things that never actually happened. In previous studies, McDermott used fMRI to document which areas of the brain are involved in the creation of false memories; eventually, it became clear that fMRI images of false memory processing also offered very robust and detailed representations of language centers, and that these results could be obtained on an individual patient basis.

McDermott and Jason Watson, a research associate in psychology, began working with neurosurgeons and radiologists at the Washington University School of Medicine who were struggling to find more effective ways of using fMRI to pinpoint language centers in patients scheduled for radical brain surgeries. She worked closely with Jeffrey Ojemann, a Washington University neurosurgeon whose father had pioneered development of electrocortical stimulation (ECS) mapping, the current “gold standard” for pre-surgery mapping of language and memory functions in the brain of an individual patient.

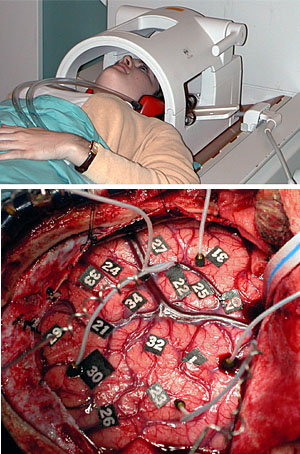

McDermott, Ojemann and colleagues hope that non-invasive fMRI testing will one day be advanced enough to provide a painless alternative to ECS mapping, a daunting procedure that requires patients to be awake and conversant while surgeons systematically probe exposed brain areas in an effort to locate and map language-related functions. The operation, which involves the removal of a softball-size section of the skull, sometimes fails because patients are unable to respond coherently during the operation.

The Washington University fMRI mapping technique also offers improvements over the Wada (WAH-dah) test, another commonly used method of locating critical language and memory regions of the brain prior to surgery.

Named for its originator, Dr. Juhn Wada, the procedure relies on the fact that language functions in most people tend to be concentrated in either the right or left hemisphere of the brain. The test, which requires a catheter to be threaded into a brain artery, allows surgeons to look for changes in language function as alternate hemispheres of the brain are put to sleep. The Wada test provides a rough idea of which hemisphere has primary control of language, but does nothing to pinpoint specific location of language areas within the hemisphere; it also provides inconclusive results when language functions are shared across hemispheres.

The Wada test is usually among the first given to epilepsy patients considering surgery to remove a section of the brain that appears responsible for triggering seizures. If a Wada test indicates that the seizures are coming from a hemisphere in which critical language and memory skills are located, surgeons may recommend further ECS testing to pinpoint how much of the temporal lobe can be removed without risking significant damage to language skills. Similar evaluations are conducted to determine if brain tumors can be removed without damaging areas of the brain critical to language and memory.

Recently, McDermott, Watson and Ojemann began administering the fMRI false memory test to patients scheduled for brain surgery and then comparing their results to those from the ECS and Wada techniques. Their study includes post-surgery evaluation to determine if language skills were actually damaged during surgery.

In the case presented in the journal Epilepsy & Behavior, the Wada test failed to identify whether the patient’s language functions were dominantly located in either the left or right brain hemisphere. Fluent speech was observed no matter which hemisphere was put to sleep. The fMRI testing revealed a non-typical, dual hemisphere location of language centers, but also indicated that few of these functions were located in the left frontal lobe, the area believed to be responsible for the patient’s seizures. ECS testing was performed just prior to surgery and its results mirrored those obtained painlessly through the fMRI test. Similar results have been confirmed in seven other patients.

“The findings from Wada, fMRI and ECS were confirmed by a lack of language impairment after left frontal lobectomy for seizures,” McDermott said. “This case illustrates that fMRI can precisely map cortical language networks in epileptic patients and that fMRI may be used to help interpret laterality results provided by the Wada procedure.”

Other members of research team and study co-authors include Monica V. Baciu, research associate in the department of radiology; Richard D. Wetzel, professor of psychiatry, neurology and neurological surgery; Hrayr P. Attarian, assistant professor of neurology; and Christopher J. Moran, professor of neuroradiology; all of the Washington University School of Medicine.

The study was supported by grants from the McDonnell Pew Program in Cognitive Neuroscience, the McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function and the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIH/NINDS Grant NS41272).

Note: Baicu, a visiting researcher at Washington University, is based at Pierre Mendes-France University in Grenoble, France. Ojemann recently relocated to the University of Washington in Seattle. Attarian is now based at the University of Vermont School of Medicine.