A research team co-directed by Erik Trinkaus, Ph.D., professor of anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis, has dated a human jawbone from a Romanian bear hibernation cave to between 34,000 and 36,000 years ago. That makes it the earliest known modern human fossil in Europe.

Other human bones from the same cave — a temporal bone, a facial skeleton and a partial braincase — are still undergoing analysis, but are likely to be the same age. The jawbone was found in February 2002 in Pestera cu Oase — the “Cave with Bones” — located in the southwestern Carpathian Mountains. The other bones were found in June 2003.

The results on the jawbone will be published the week of Sept. 22 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS; www.pnas.org) Online Early Edition. A report on the other bones will appear in an upcoming issue of the Journal of Human Evolution (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00472484). The finds should shed much-needed light on early modern human biology.

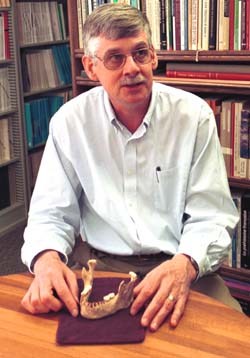

“The jawbone is the oldest directly dated modern human fossil,” said Trinkaus, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor of Anthropology in Arts & Sciences. “Taken together, the material is the first that securely documents what modern humans looked like when they spread into Europe. Although we call them ‘modern humans,’ they were not fully modern in the sense that we think of living people.”

To determine the fossils’ implications for human evolution, Trinkaus and colleagues performed radiocarbon dating of the jawbone (dating of the other remains is in progress) and a comparative anatomical analysis of the sample. The jawbone dates from between 34,000 and 36,000 years ago, placing the specimens in the period during which early modern humans overlapped with late surviving Neandertals in Europe.

Most of their anatomical characteristics are similar to those of other early modern humans found at sites in Africa, in the Middle East and later in Europe, but certain features, such as the unusual molar size and proportions, indicate their archaic human origins and a possible Neandertal connection.

The researchers document that these early modern humans retained some archaic characteristics, possibly through interbreeding with Neandertals. Nevertheless, because few well-dated remains from this period have been found, the fossil remains help to fill in an important phase in modern human emergence.

“The specimens suggest that there have been clear changes in human anatomy since then,” said Trinkaus. “The bones are also fully compatible with the blending of modern human and Neandertal populations. Not only is the face very large, but so are the jaws and the teeth, particularly the wisdom teeth. In the human fossil record, you have to go back a half-million years to find a specimen that has bigger wisdom teeth.”

The jawbone was found by three Romanian cavers, who contacted Oana Moldovan, director of the Institutul de Speologie, a cave research institute in Cluj, Romania. Moldovan in turn, recognizing the importance of the jawbone, contacted Trinkaus.

The two met in Europe in May 2002, and Trinkaus brought the jawbone temporarily to Washington University for analysis. Trinkaus, Moldovan, the cavers and Ricardo Rodrigo, a Portuguese archaeologist, returned to the cave in June 2003 to produce a map and survey the cave’s surface. In the process, the cavers and Rodrigo found the facial skeleton, temporal bone and other pieces that are now undergoing analysis.

Since then, Trinkaus and Moldovan have assembled an international team to document and excavate the cave and analyze the material after it comes out from the cave. The cave was primarily used for bear hibernation. It is not known how the human bones got into the cave, but Trinkaus says one possibility is that early humans used the cave as a mortuary cave for the ritual disposal of human bodies. Some of the bear bones were rearranged by humans, documenting past human activities in the cave.

“The jaw was originally found sitting by itself; the material this summer was found mixed up with bear bones,” Trinkaus said. “After they found the face, they collected everything on the surface that might be human, packaged it up and brought it out of the cave. Some of the pieces that they carried out of the cave are, in fact, bear. We know that more of the skull is in the same place, but it was buried or not recognized at the time.”

The team plans to return to Romania next summer to continue the scientific analysis of the cave and its contents.