What once could be a severely painful experience now may be no more than a temporary inconvenience. Back surgery — typically an intimidating prospect fraught with tales of post-operative pain — is being performed with less pain, less blood loss and fewer days recovering in the hospital, thanks to a combination of minimally invasive surgical techniques.

According to Neill M. Wright, M.D., assistant professor of neurological surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the School of Medicine is one of only a handful of centers in the country using this combination of techniques, but promising results may inspire others to follow suit.

“I think this is going to spread like wildfire across the country, because it has several major advantages compared to other surgical techniques,” Wright says. “Patients are in the hospital for far less time, they lose significantly less blood and they’re in much less pain. For those reasons, it’s really changing how we view spinal fusion surgery.”

Typically, patients with severe, chronic back pain or degenerative disc diseases undergo a traditional operation called posterior lumbar interbody fusion. A large incision is made in the center of the back and the muscles surrounding the spine are pried apart. After removing any bone or disc tissue pressing against nerves and causing pain, a piece of bone is grafted onto the damaged portion of the spine with screws and rods holding it in place. As the bone graft heals, it fuses with the surrounding vertebrae and provides structural support and stability.

Because the back muscles must be stretched out of the way during surgery, healing takes several days and patients often are in more pain the week after surgery than before. They typically spend about six days in the hospital recovering from the procedure, and are on heavy doses of IV pain medications for the first few days.

So spine surgeons have been trying to limit post-operative pain from back surgery using the same ideas that have made gallbladder and knee surgeries less invasive. To do so, they are combining two surgical techniques already approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

First, instead of making a six-inch incision down the center of the back and stripping away the surrounding muscle, Wright uses a series of small tubes to get to the spine. The smallest tube is inserted first, followed by a slightly larger one threaded directly over the initial tube, and so on, slowly easing the underlying muscle aside. Finally, a pipe about as wide as a nickel is placed over the tubes, which then are removed. Through this small passageway a surgeon can remove any bones or discs that are putting painful pressure on nerves, and can position a new bone graft.

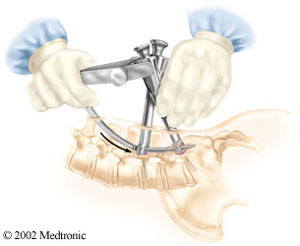

To keep the graft in place, Wright employs a second minimally invasive technique using a percutaneous screw system. Instead of opening the back to insert screws, X-ray images are used to navigate two screws through the skin and orient them appropriately in the spine. An “arm” with a rod extending from its tip is attached at a right angle to the two screws, and as the rod arcs down and penetrates the skin, it automatically is aligned with the screws, locking them in place. Rather than leaving a big scar, the three small holes created by the two screws and the sextant typically disappear in the weeks following surgery.

In addition to reductions in pain and length of hospital stay, combining the use of these two minimally invasive procedures cuts blood loss during surgery by about one third.

“So far this appears to be just as effective in relieving pain and inducing fusion as traditional spinal fusion surgery,” says Wright. “And because there’s less blood loss, it may even be safer. We currently are compiling long-term results to document these benefits, but even before we have definitive data, it’s clear that this technology already has made back surgery more bearable for several of my patients.”