The lightning speed with which scientists developed and tested the COVID-19 vaccine is a true scientific triumph — one that would not have been possible without the more than 70,000 volunteers who participated in clinical trials of the vaccine.

Public participation is critical to the success of any medical research. Yet recruiting volunteers for trials is increasingly challenging. New research from Washington University in St. Louis suggests the widening ideological gap in the U.S. may contribute to these challenges.

Researchers found evidence that Americans approach opportunities to contribute to medical research with either a general aversion or an inclination to participate. This research concludes that propensity is driven, at least in part, by political ideology.

While much attention has been given to Black people’s distrust in the medical system and research in particular, the current study — published in Scientific Reports — is the first to demonstrate the effect of political ideology on willingness to trust science and participate in medical research.

“Our research shows that conservatives are less willing to participate in medical research than are liberals. This difference is due, in part, to ideological differences in trust in science,” said Matthew Gabel, professor of political science in Arts & Sciences.

There are potential consequences to this divide.

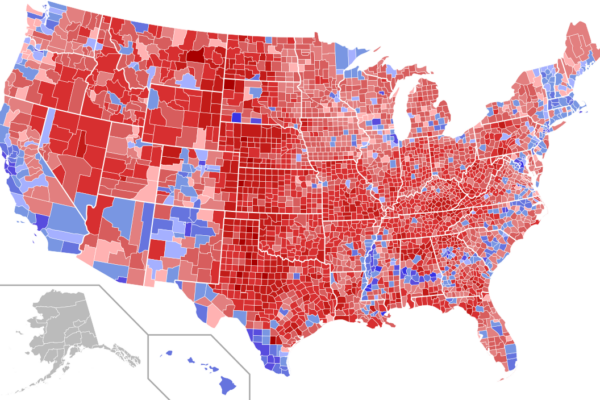

“An ideological divide in such participation could undermine both the execution and quality of medical research,” Gabel said. “Given the uneven geographic distribution of political ideology, our findings raise important issues for recruiting study participants and developing political support for medical research. It could also threaten the generalizability of medical studies since important types of health behaviors, such as smoking, vary with Americans’ political ideology.”

A problem decades in the making

The problem has been brewing for decades. However, the issue did not receive significant media attention until recently, when the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the stark contrasts between liberals and conservatives. For example, a new nationwide study found Independents and Republicans were about three times more likely to express resistance to the COVID-19 vaccine than Democrats.

Long before the pandemic, though, Gabel saw the writing on the wall. He and John C. Morris, MD, the Harvey A. and Dorismae Hacker Friedman Distinguished Professor of Neurology and head of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the School of Medicine; Catherine M. Roe, associate professor of neurology at the School of Medicine; and Stanford University’s Jonathan Gooblar, wanted to better understand why some people were more inclined to participate in medical research than others.

“The value of research with human subjects depends critically on successful recruitment of a representative group of participants. To do that, we have to know sources of bias in who is recruited and who is likely to accept invitations to participate,” Gabel said.

The researchers analyzed survey data from the July 2014 and September 2015 waves of The American Panel Survey, a survey managed by Washington University’s Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy. The survey asked questions about past and future participation in medical research-related activities: a clinical trial for a drug, a long-term observations study, a fundraiser for medical research and blood donation. It also included hypothetical questions about one’s willingness to donate an organ upon death and willingness to participate in an Alzheimer’s disease study. They restricted their analysis to respondents 45 years of age or older, as younger respondents would generally have been ineligible to participate in the long-term studies, clinical trials and hypothetical Alzheimer’s Disease study. Altogether, the analysis included 1,132 respondents.

“If we want to reduce or eliminate the ideological difference in participation in medical research, we can do some of that by trying to raise trust in science among conservatives. But even if we are very effective at doing that, my analysis shows that conservatives will still be less likely to participate for ideological reasons unrelated to trust in science.”

Matthew Gabel

Lack of trust is only part of the problem

The researchers found those with conservative ideology have a systematically lower propensity to participate in medical research, due in part to their lower levels of trust in science. But lack of trust in science only accounted for about a quarter of the effect.

“This means that if we want to reduce or eliminate the ideological difference in participation in medical research, we can do some of that by trying to raise trust in science among conservatives,” Gabel said. “But even if we are very effective at doing that, my analysis shows that conservatives will still be less likely to participate for ideological reasons unrelated to trust in science.”

This rift is a threat to the generalizability of medical studies.

“The ideological divide in participation in medical research suggests that clinical trials and other long-term observational studies likely over-represent those with liberal political ideology. This can impact the quality of studies because significant health conditions and behaviors — such as smoking, excessive drinking, diets and mortality rates — differ with political ideology,” Gabel said.

“Given the number and political importance of conservatives, and the relative stability of Americans’ ideological commitments, this divide could signify a significant obstacle for the practice, advance and influence of science in the United States,” Gabel said.