Around 75% of older Americans live in the suburbs, areas that were designed in the 1950s and 1960s with the automobile front of mind. Usually, it takes a car to even run simple errands. The problem? Not everyone in a community has the ability (or desire) to drive. This is true of us when we’re young and as we age.

Issues like this have arisen in the United States and other countries around the globe as life expectancy increases. In 2017, 16% of the U.S. population was over 65 years old, and that number is expected to reach 22% by 2050.

“Communities were developed when people lived not nearly as long,” says Nancy Morrow-Howell, the Betty Bofinger Brown Distinguished Professor of Social Work and director of the university’s Harvey A. Friedman Center for Aging. Now, life expectancy is 78 years, much longer than the average life span of 62 years when Social Security was introduced in 1935.

“Today, more generations are alive at the same time,” says Brian Carpenter, professor of psychological and brain sciences, who along with Morrow-Howell teaches “When I’m 64,” a class for first-year under‑ graduate students about aging. “You’re not going to have just grandparents in the picture; you’re going to have great-grandparents. Families and communities are really going to be multi-multigenerational.”

That means communities are going to have to become intergenerational to address the needs of a more age-diverse group of people. Intergenerational communities can be navigated by everyone, including new parents and their infants, latchkey kids, older adults and people living with disabilities. One way to do that is with universal design.

Spaces “were originally built by mostly men who imagined themselves to be these perfect 6-foot specimens,” says Susan Stark, associate professor of occupational therapy at the School of Medicine. Stark also team-teaches “When I’m 64.” “Even kitchens were designed to fit men’s bodies and not necessarily women’s bodies. And we had this Peter Pan syndrome going on where we thought our bodies would never change. But nobody is static.”

Universal design shifts that thinking even in the smallest ways. A typical round door handle, for instance, is difficult to open for people with arthritis and for kids. A lever handle offers access (quite literally) to more people.

“It’s really obvious to people when they enter a space that’s not built to accommodate them,” Carpenter says. “And it sends a subtle or not-so-subtle message about how welcome they are in those spaces.”

But designing inclusive communities is about more than accommodating people. Different design principles make people more social, increase civic participation, allow people to find and retain employment, and encourage respect and social inclusion.

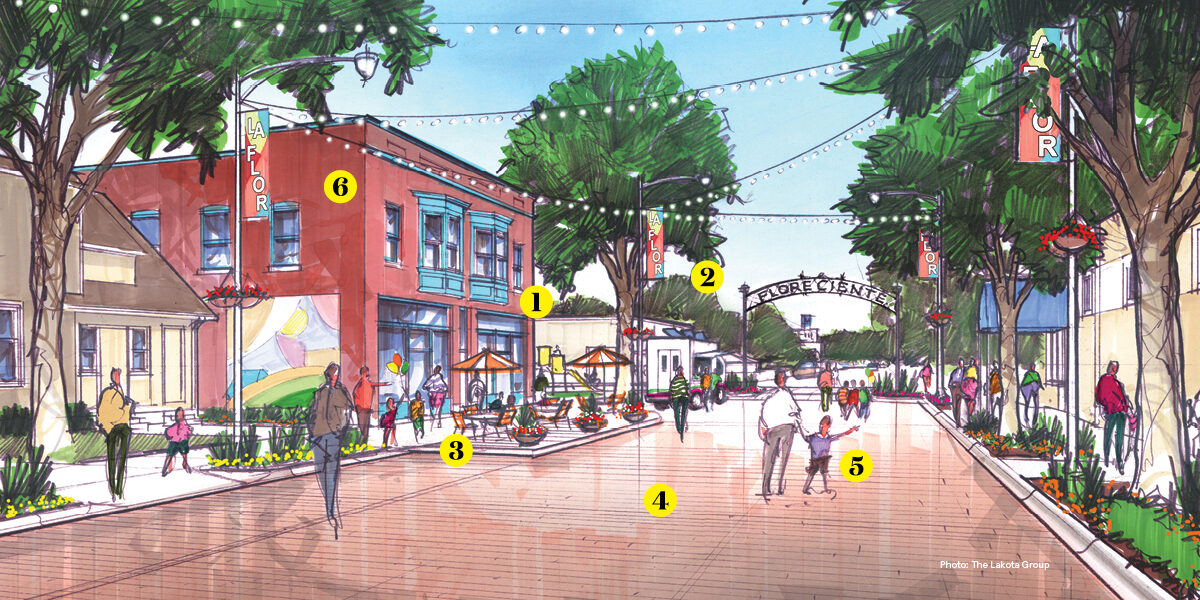

One way to do that is to build communities that don’t rely so heavily on cars for transport. “Walkable communities are important for a lot of reasons,” Stark says. “Older adults don’t have to drive. Children can walk safely if there are pedestrian walkways. It’s better for people’s overall health. There’s less social isolation; if you’re walking on the street, you see people versus driving into your garage and shutting the door.”

A walkable community heightens the visibility of everyone in the community as well, allowing people to see how diverse their neighbors are and raising awareness about needs for increased accessibility.

But making these changes is difficult. “It took us forever to build our highway system,” Morrow-Howell says. “Now we’ve got it, and that means cars. To substantially replace roads and highways with public transportation options is a humongous deal.”

“We need to get people to conceptualize accessible design in the same way as safety guidelines,” Stark says.

Although there are guidelines issued by the World Health Organization, AARP and other organizations on what intergenerational communities look like, there is still a shortage of policy to make inclusive communities. But even small changes — adding more benches in areas with lots of pedestrians, more pedestrian crosswalks with longer signals and more public toilets — can make a huge difference to a lot of people.

“If we’re going to live longer, people don’t want to stop working and then do nothing for all those remaining years,” Carpenter says. “They want to stay connected not just to their family, but also to their friends and their community. So the community has to respond to that and figure out how to keep everyone engaged, included and involved.”