As a worldwide pandemic washes over the St. Louis region, the Washington University Medical Campus is eerily quiet. Most visitors, students, staff and research faculty are no longer on campus. Limited patients come to its medical buildings, as many appointments are taking place virtually on video screens.

But it’s another story in the COVID-19 wards of Barnes-Jewish Hospital (BJH), where Washington University physicians are fighting an exhausting battle against a new, baffling and sometimes lethal disease with the help of the hospital’s nurses, other medical professionals and support staff.

“When the very first suspected COVID-19 patient was admitted to our hospital in early March, I volunteered to take care of him,” said hospitalist Han Li, MD, an instructor in Washington University’s Division of Hospital Medicine. “And then, we went just from that one patient to the next day having two, three and then more than 100 patients on our floors. We have all been thrown into the fray, and we’re focused on figuring out how to get every patient the care they need. There are no firm guidelines because it’s a completely new disease, but we are learning new information almost daily. I think we’re going to look back on this in a few months, and only then will we have the time to really process things and reflect.”

Long before the first case was diagnosed in the St. Louis region, Washington University physicians and BJH started preparing, with support from BJC HealthCare.

“In January, before the United States felt any impact from the coronavirus, we worked with BJH and BJC to start planning how we would care for patients with COVID-19 — specifically, where we would care for them, who would provide that care, how we would outfit our health-care workers with personal protective equipment — so when the number of patients started to surge in March, we could handle it,” said William G. Powderly, MD, the Dr. J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine and co-director of the Division of Infectious Diseases. “We had very little information in the beginning about how to treat this disease, so our physicians had to think on their feet when the answers weren’t available through limited existing research and clinical accounts of others confronting the virus. The creativity, flexibility and dedication our health-care providers have shown in the face of this novel and sometimes deadly virus has been extraordinary. They are true heroes.”

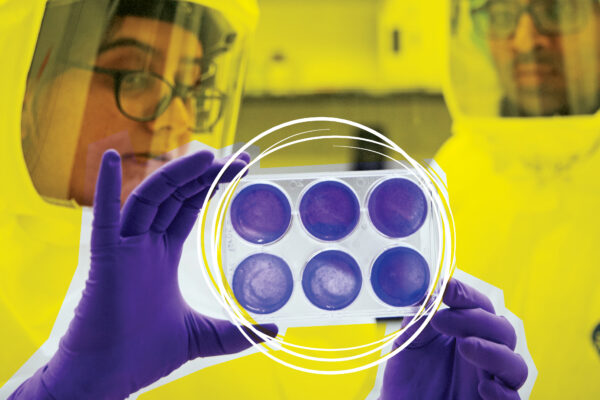

Several specific areas of the hospital and five intensive care units were dedicated to COVID-19. BJC and university logisticians obtained massive quantities of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as masks, gowns, face shields, gloves and goggles for front-line medical staff. Hospital managers shuffled work schedules so there would be enough attending physicians from the divisions of general medicine, infectious diseases, and pulmonary and critical care available to care for the dozens of cases expected to arrive.

“Because of all the planning, the workload has been manageable, but the actual work is much more difficult than usual,” said Komo Gursahani, MD, an associate professor of emergency medicine at the School of Medicine and assistant director of the BJH emergency department. “Just the donning and doffing of personal protective equipment repeatedly can add a lot of stress because we have to be very careful with how we put the equipment on and remove it so we don’t contaminate ourselves. And we have to be cognizant that every test we order – whether it’s X-rays or CT scans or some other diagnostic – requires someone to have contact with the patient. So every decision we make now comes with a little added factoring in of how much we’re exposing our colleagues and coworkers to potential disease.”

To minimize the number of health-care workers exposed to the virus, most medical trainees at BJH — interns, residents and fellows — have been redeployed to care for other patients, and care teams have been pared down. Where six people previously might have entered a room to check on a patient, now only two or three go in.

In the early days of the pandemic, doctors thought that the majority of COVID-19 patients who became critically ill had developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS can be triggered by a variety of infectious and noninfectious causes. The condition is very serious, but pulmonary and critical care physicians have been trained to treat it. As the number of cases grew, however, doctors around the world began to realize that not all COVID-19 patients’ respiratory symptoms looked like ARDS. And the doctors started to note other complications. Some patients developed heart problems and died of cardiac arrest. Some were caught in a “cytokine storm,” which occurs when their own immune systems overreact to infection and produce disastrously high levels of immune proteins. Some developed unusual blood-clotting problems that were hard to detect and treat. Clots are very dangerous because they can block blood vessels, leading to respiratory failure, heart attacks, strokes, kidney damage and other serious complications. Some patients developed strokes, seizures, confusion or other neurological problems. In short, COVID-19 was unlike any virus they had seen before.

To handle a disease of this complexity, doctors rely on a team of BJH nurses, respiratory therapists and other medical professionals who provide much of the day-to-day care for COVID-19 patients, and a large team of specialists who help guide the care. A multidisciplinary COVID-19 critical care task force that includes physicians from pulmonary medicine, emergency medicine, surgery, cardiology, anesthesiology, neurology, medical ethics and other fields has been set up to make recommendations for patient care. Every day, the intensive care physicians caring for COVID-19 patients meet with specialists in infectious diseases, pulmonary and critical care medicine, nephrology (kidneys), cardiology and other fields for 90 minutes to discuss the care of each of the critically ill COVID-19 patients.

“The information on COVID is always changing and always increasing,” said Colleen McEvoy, MD, an assistant professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine who co-leads the COVID-19 critical care task force. “We’ve reached out to colleagues around the country and around the world for information on COVID. We’re drawing on the experience from China, from Italy, from the coasts where they’ve had more patients. We have discussions at all hours of the day and night, to make sure that every day we’re doing the best we can for patient care with the information we have at the moment.”

The more that is learned about COVID-19, the more clear it becomes that the disease does not hit all communities equally.

“In my area, the vast majority of patients are African American,” said Cristina Vazquez Guillamet, MD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases and pulmonary and critical care medicine who works in the COVID intensive care unit. “That reveals the fact that the U.S. health-care system has not been doing a good job of taking care of everybody up to this time. If there is a silver lining to this pandemic, I hope it is that we become more aware of health-care disparities and make health care better for everyone.”

A tragedy of contagious diseases is the isolation it imposes on people who contract the illness. Some people seriously ill with COVID-19 drive themselves to the hospital to avoid asking family or friends for a ride. Some arrive in ambulances, accompanied only by paramedics. Family members who bring a patient to the hospital aren’t allowed into the emergency room. They drop off their loved one, leave a name and phone number with the emergency room staff and drive away. Once admitted to the hospital, some COVID-19 patients stay two or three weeks and, for everyone’s safety, family members are rarely allowed to visit.

“One of the most challenging things right now is the distance between patients and families,” said Patrick Lyons, MD, an instructor in pulmonology and critical care medicine who cares for COVID-19 patients in intensive care. “We’re so used to being able to have loved ones at the bedside with us, to hold the patient’s hand, be with us as we talk them through what’s going on and what’s likely to happen. Now patients don’t have that support.”

Added Vazquez Guillamet: “At points, you feel that you’re the physician but you’re also the family member. Sometimes you have people who are obviously scared, and there’s nobody around, so we do what we can to comfort them.”

After their morning rounds to check on all patients and deal with any urgent needs, physicians spend part of each afternoon calling family members to update them. Those patients who are healthy enough to communicate can use the landline by each bed or their own cellphones to call family and friends. Nurses bring in iPads so those without smartphones can video chat with their families. Medical staff have begun distributing cards with their pictures on them to the patients to show that there are, indeed, human beings underneath all the PPE.

COVID-19 has required medical professionals to take risks and make sacrifices like no other group in society. Thousands of health-care workers nationwide have contracted the virus. To avoid exposing her family should she be infected, Vazquez Guillamet has moved into temporary housing in the Knight Center on the Danforth Campus with her husband, Rodrigo Vazquez Guillamet, MD, an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. He also is caring for COVID-19 patients in intensive care units. The housing is provided free of charge by Washington University to essential staff at the School of Medicine and BJC HealthCare fighting COVID-19. The Vazquez Guillamets’ two young children are being cared for by their grandparents. The parents work for nine days at a stretch, take another three days to make sure they’re not infected, and then go home to spend a few days with the children before returning to the intensive care units.

“The danger is there; we know it’s there. You don’t see it with a naked eye because you can’t see a virus with a naked eye, but we know it’s there,” Cristina Vazquez Guillamet said. “It’s hard. I miss my kids. My husband normally wears a beard, but he shaved it off so the N95 mask would fit better. So when my 4-year-old saw him, he didn’t recognize him. This has been very hard on our family.”

For the doctors, the work is exhausting, physically and emotionally. But at the same time, it is what they are trained to do as physicians.

“We get inundated on a daily, hourly basis with patients being admitted to the intensive care units, and some of them are dying,” said Gerome Escota, MD, an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases. “It has really been hard. But I think the best way to deal with it is to go back to the main reason we became doctors: to help people in crisis. You can’t ever prepare for a pandemic, of course, but all those years of medical school, postgraduate training, have taught us how to adapt to any situation and handle a crisis. It’s like you’re riding a different bike now; while it feels new and difficult, it’s important to remember that it’s still a bike. Even if the bike feels foreign, we have the skills to apply to this situation.”

Added Gursahani: “When this was just beginning, maybe the second week of March, I was working from home, doing a lot of planning and administrative work. That whole time, I was getting more and more anxious. When I finally got back to the hospital, I felt a lot better. As emergency medicine physicians, we are extremely skilled in operating in a world of uncertainty. And it’s scary, of course, to be faced with this disease and all the risk of exposure, but all of that anxiety I was feeling in the planning went away. I’m with my team. I’m with all the people who have my back, doing what I’m trained to do.”

WashU Response to COVID-19

Visit coronavirus.wustl.edu for the latest information about WashU updates and policies. See all stories related to COVID-19.