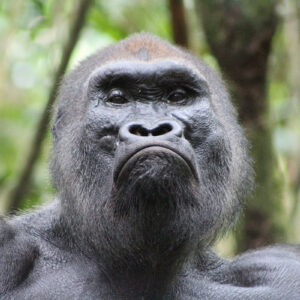

The social life of gorillas is much more dynamic than previously thought, particularly with regard to interactions between neighboring groups.

New research led by anthropologists at Washington University in St. Louis shows that encounters between gorilla groups were much more frequent, and that they had more varied social exchanges than expected.

Further, these interactions seemed to be driven more by defense of mates than food resources. While members of different groups were observed engaging in direct competition, gorillas from different groups also engaged in friendly interactions such as play. The study is published in the International Journal of Primatology.

“Interactions with other groups are critical for wild gorillas,” said Kristena Cooksey, a graduate student of biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences and first author of the new study. “They provide a way to gain information about the power of dominant males in neighboring groups and their support systems and also about potential reproductive opportunities.

“Females born within the group will eventually leave to join a different group to avoid inbreeding and should be selective about which male’s group they choose,” she said.

“Close encounters between gorilla groups inform their decision making.”

Broader range of interaction

While mountain gorillas in East Africa have been studied for more than 50 years, relatively little is known about the behavior and social lives of their counterparts in central Africa.

Through a long-term collaboration with the Congolese government and Wildlife Conservation Society, research from Washington University is changing perspectives on gorilla behavior, ecology and health — and how these factors interact in a changing world.

Based on years of work following several gorilla groups, the new study paints a more complete picture of the variation in the interactions between neighboring gorilla groups in the forested environment, where western lowland gorillas spend most of their time. In total, researchers spent more than 2,797 days observing interactions between gorilla groups in the Goualougo Triangle and Mondika, located in the northern Republic of Congo.

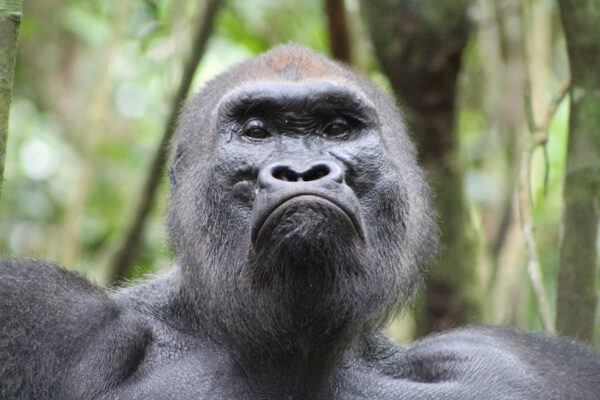

“One of the advantages that we had going into this study was the expertise of the research teams who conduct daily follows of these gorilla groups and who had spent years earning the trust of these elusive apes that are typically wary of human presence,” said Crickette Sanz, associate professor of biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences.

“Many of the researchers and trackers have known these particular gorillas for decades and immediately detected when other groups were in the area by the responses of the focal silverback’s reaction,” Sanz said, using a common descriptor for the dominant male in the gorilla social group.

“Some of the gorillas born in our focal groups have settled in nearby groups and so are familiar with human observers,” she said. “This enabled us to document a broader range of social interactions between wild western lowland gorilla groups than had previously been documented. Further, we were able to pair this information with food availability and overall ape distribution across the region.”

Benefits and risks of encounters

Gorillas are known for having stable yet competitive social structure. Western lowland gorillas typically reside in groups with one adult dominant male, multiple adult females and their offspring. However, other social groups have been observed, including bachelor groups and solitary males.

Encounters between groups and solitary males were among some of the most aggressive interactions observed, particularly if mating opportunities were at stake.

The researchers found no relationship between the rate of encounters and seasonal fruit availability — which is known to elevate competitive interactions in other nonhuman primates.

“We found that the number of supporting males in a group influenced intergroup encounter rates and outcomes,” Cooksey said. “The more supporting males are present, the less likely an intergroup encounter would occur. In contrast, affiliative behaviors such as extended play bouts were also observed between individuals in different groups.”

These romps surprised the researchers.

“We really had not expected to see so much tolerance between members of different groups,” Sanz said. “This indicates broader social networks among groups.

“Such extended sociality holds potential benefits in terms of identifying potential mates and maintaining socially acquired skills such as traditions or cultural behaviors, but may also pose significant risks in terms of infectious disease transmission,” Sanz said.

Wild gorilla populations were decimated by an Ebola outbreak in western and central Africa in the early 2000s. In some locales, it’s estimated that over 90% of the gorilla population was lost due to Ebola. The catastrophe led the World Conservation Union to designate the western lowland gorilla a critically endangered species.

Shifting into new home ranges

Habitat alteration is one of the major threats to remaining western lowland gorillas.

“As humans encroach upon gorilla habitats, gorilla social units are more likely to spatially shift into the home ranges of other groups — which could trigger a cascade of potentially detrimental social and health outcomes,” said David Morgan, co-principal investigator of the research project and research scientist at the Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes at Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. “These include higher rates of intergroup interactions and more intense competition over resources.

“Disturbance-induced increases in contact between groups could also result in higher transmission of infectious diseases, another major threat to wild gorillas,” Morgan said. “Western lowland gorilla populations are declining, and it is urgent that we continue to rigorously and empirically assess the complex interrelationships between factors impacting their survival.”