It has been nearly 75 years since the end of World War II, yet its legacy of xenophobia, political intolerance and radical political parties continues to plague Germany and the rest of Europe. A new study from Washington University in St. Louis finds that living near former Nazi-era concentration camps is, in part, to blame.

Leveraging survey and electoral data, the researchers found that living closer to a Nazi-era concentration camp was associated with an increase in out-group intolerance and support for radical parties. They also found preliminary evidence of this connection in other parts of Europe, where the Nazi regime had set up concentration camps. They believe these behaviors are driven by cognitive dissonance.

“The role of the concentration camps was to hold the so-called racially undesirable elements, which referred to Jews and other racial and ethnic outgroups. The camps epitomized the racist philosophy of the regime and took racial hatred to its extreme,” said co-author Margit Tavits, professor of political science in Arts & Sciences.

“Because the concentration camps were integrated in the local economy, locals, who were otherwise tolerant of outgroups, had to witness the inhumane treatment of non-Germans. One way to deal with such dissonance is to change one’s attitudes to be in accordance with the new reality: to start believing that the people held in these camps, i.e. racial and ethnic outgroups, deserved the treatment they received. In short, through cognitive dissonance, these camps could have led to an increase in xenophobia and intolerance at the time.”

“Legacies of the Third Reich: Concentration Camps and Out-group Intolerance,” forthcoming in the American Political Science Review, was co-authored by Tavits, Jonathan Homola of Rice University and Miguel Pereira, a PhD candidate at Washington University.

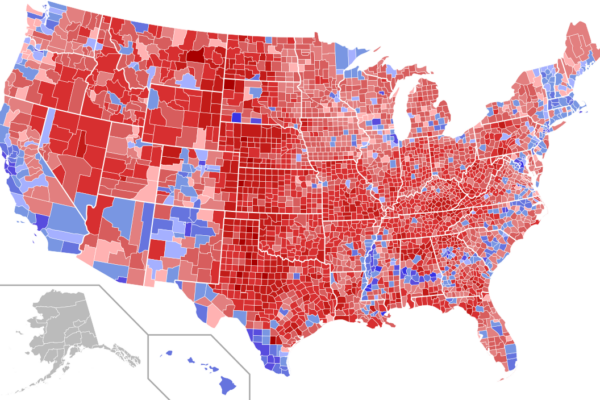

Using survey responses from the European Values Study and the German General Social Survey, the researchers found that a 50 kilometer (31 mile) increase in distance to the closest camp was associated with a decrease of 0.10 points in out-group intolerance. That translates to roughly a two-point shift on the 10-point conservatism scale. Using electoral data, the results show that a 50 km increase in distance leads to about one percentage point decrease in vote share for the extreme right-wing parties.

“The effects that concentration camps had on attitudes did not end with the Holocaust and have been passed down through generations, which is why we still observe higher intolerance among people who live closer to the former concentration camps,” Tavits said.

Previous research in the U.S. has established a similar link between racial resentment and proximity to areas that once were home to a large number of slaves.

“This is very relevant in the context of recent political developments on both sides of the Atlantic that have brought xenophobia and intolerance back into the limelight — because it helps us better understand what makes exclusionary political appeals attractive,” Tavits said.

How then can the cycle be broken? The findings suggest that educating the public about the atrocities that were committed offers a path to mitigate the long-term effects of cognitive dissonance produced during the Nazi era.

In present day, the sites of most German concentration camps are used as a memorial, documentation center or museum. The researchers found that the effects of camp proximity were stronger for camps that have a less noticeable presence today, i.e., those without original structures and museums.

“Being able to see the actual structures of the institutions where atrocities were committed is likely to leave a strong impression on individuals visiting the camp locations,” Tavits said. “These findings take us a step closer to identifying ways to break the seemingly deterministic persistence of the effect of past institutions and affirms that efforts to re-educate the population may not be in vain.”