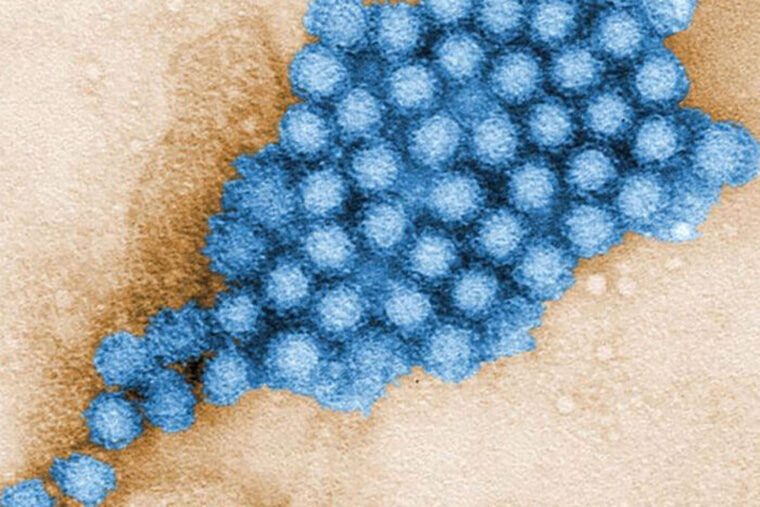

The highly contagious norovirus causes diarrhea and vomiting and is notorious for spreading rapidly through densely populated spaces, such as cruise ships, nursing homes, schools and day care centers. Each year, it is responsible for some 200,000 deaths, mostly in the developing world. There are no treatments for this intestinal virus, often incorrectly referred to as stomach flu.

Now, a new study led by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has shown that gut microbes can tamp down or boost the severity of norovirus infection based on where along the intestine the virus takes hold.

The study, published Nov. 25 in the journal Nature Microbiology, suggests new routes to possible therapies for norovirus infection. Collaborators included researchers at the University of Florida, the University of Michigan and Yale University Medical School.

“There are currently no treatments for norovirus, which is very easily spread through fecal-oral transmission,” said co-senior author Megan T. Baldridge, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at Washington University. “Norovirus is especially dangerous in young children, older adults and people with compromised immune systems. We are trying to understand how the gut microbes interact with norovirus in an effort to pursue new therapeutic strategies.”

In these mouse studies, the researchers found that normal gut bacteria boosted the severity of viral infection in the lower small intestine, which is in line with past work in the field. But simultaneously, normal gut bacteria blocked or inhibited viral infection in the upper small intestine. In other words, gut microbes can have totally opposite effects on norovirus infection depending on the infection’s location along the length of the gut.

“These results were a huge surprise to us,” Baldridge said. “We showed that different parts of the intestine can show dramatically different responses to this type of infection. Our research reveals that we can’t view the gut as a homogeneous tube that responds to infection in a uniform way.”

Baldridge and her colleagues found that the difference in response was driven by bile acids, which are mainly known for their roles in digestion.

“Bile acids are powerfully regulated by bacteria all along the gut,” Baldridge said. “But there had not been a realization that these bile acids could prime the gut to mount an immune response against intestinal viruses.”

In the new study, the researchers showed that bile acids in the upper small intestine — but not the lower — stimulated the immune system to respond to the infection. The researchers determined that bile acids in that region of the gut triggered a molecule called interferon III — one of the body’s key antiviral defenses in the intestine — to become activated.

Baldridge noted that this complexity of interactions between gut microbes and bile acids could explain some of the variability seen in norovirus infections. Some people become extremely ill with this virus; others develop no symptoms at all.

“The different ways people respond to viral infections could be related to their individual gut microbial community,” Baldridge said. “The severity of an infection could be tied to where exactly along the gut you get an infection, and that might be controlled by your individual microbiome. Subtle differences along the intestine could end up having dramatic effects on how the gut perceives the virus and responds to it.”

Baldridge also said that this changes how researchers might think about strategies to protect against or treat norovirus infection. They might seek ways to expand the immune interferon signaling that they observed only in the upper small intestine such that it extends along the entire length of the gut, for example.

She and her colleagues are planning more studies to help investigate whether there may be ways to manipulate the gut environment — through bile acids or the microbiome itself — to stimulate the immune system in ways that could shut down norovirus infection.