Graduation is still years away, but Washington University in St. Louis first-year student Caroline Foshee said it’s never too early to prepare for life after college. She’s not alone. A growing number of first-year students are seeking career advice and resources early in their college careers.

“Being interested in economics and anthropology, I get a lot of, ‘Well, what are you going to do with that?,’” Foshee said after attending a Career Early Action workshop with Mark Smith, associate vice chancellor and dean of career services. “So I want to expose myself to as many options as possible as early as possible.”

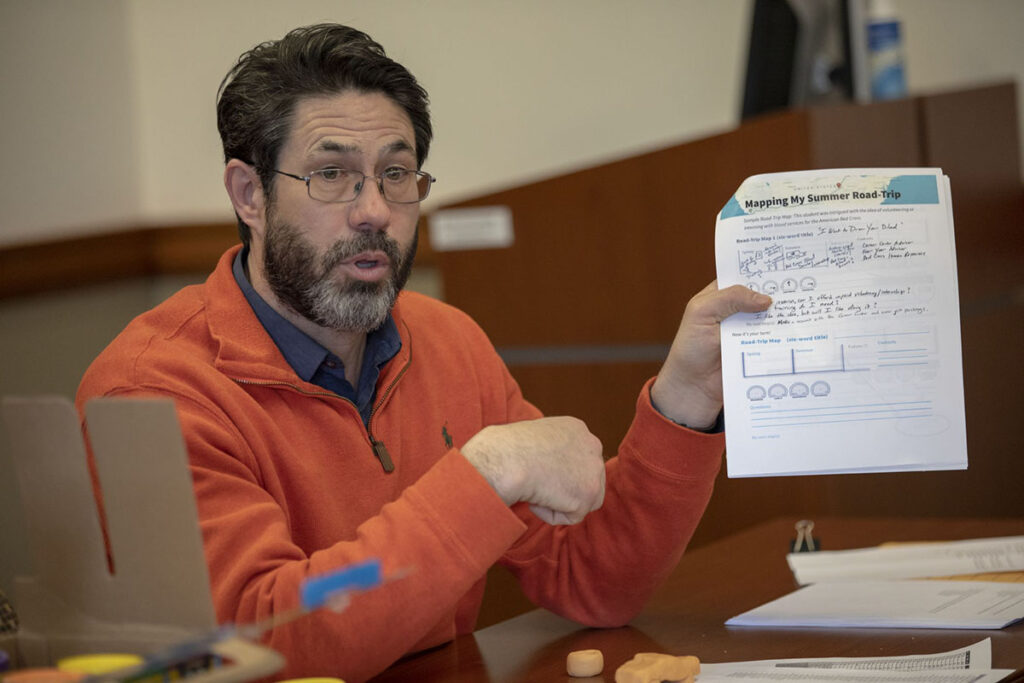

To meet growing demand, the Career Center has launched a number of new career readiness programs specifically for first-year students. At last semester’s 10 Career Early Action workshops, Smith offered practical how-to advice (open a LinkedIn account, tap your parents’ friends and your friends’ parents for informational interviews) to about 400 first-year and sophomore students. And at this week’s First-Year Exploration Week, the Career Center will host casual drop-in advising sessions, where students can learn how to make the most of summer break.

In addition, the Career Center and the College of Arts & Sciences have piloted a new program that incorporates career planning into academic advising.

“We’re seeing much more engagement earlier,” said Smith, noting that first-year students are joining career interest groups, attending career fairs, consulting with advisers and tapping into the Career Center’s internship stipend program. “To prepare for a career, you need to build skills, experience and connections — and that takes time.”

Smith didn’t always see it that way. When he first joined the Career Center in 2005, he resisted targeting new students for fear he would stress them out. But the job market has changed. The hiring process has accelerated in fields such as finance, technology and consulting. Sophomores now jostle for internships that once went to juniors.

Students have changed too, Smith said.

“I’ve talked to them, and they can handle it,” Smith said. “And we’ve been very thoughtful about our approach. We’re not saying, ‘You have to know exactly what you are going to do.’ We are saying, ‘Start thinking about it. You are going to change. That’s fine.’”

Merging academic and career advising: a new model

In addition to new services, the Career Center is helping faculty better support students in their career planning, a strategy recommended by Provost Holden Thorp in his new book “Our Higher Calling: Rebuilding the Partnership between America and Its Colleges and Universities.”

Thorp writes that parents expect their significant investment in their child’s education will yield a good job after graduation. And, indeed, Washington University’s own survey of prospective parents shows that comprehensive career services is top priority when picking a school. No surprise there. Yet some faculty bristle at the idea of college as a vocational school and are reluctant to add career advising to their long list of duties.

“Many in the academy believe that focusing chiefly on employment cheapens the goals of liberal education in producing the habits of mind for engaged citizenship and personal fulfillment,” write Thorp and his co-author, Buck Goldstein of University of North Carolina.

Thorp’s response: It’s too late to turn back now.

“If we were going to make the case that college is just about being an educated citizen, then we missed the opportunity to do that decades ago,” Thorp said in an interview. “The truth is colleges weren’t transparent with faculty that we are on the hook to provide good employment for our graduates. But universities can no longer segregate career services in student affairs departments and not ask faculty to engage in this work.”

The PACE (Personal, Academic and Career Exploration) pilot program, a new collaboration between Arts & Sciences and the Career Center, offers a new model, said Matt DeVoll, assistant dean for Arts & Sciences, who established the program with Aimee Wittman, executive director of the Career Center.

“Arts & Sciences doesn’t have the same model as professional schools, where you may pursue a career with the same name as your major,” DeVoll said. “The question becomes, How do we help them reframe understanding the undergraduate experience as one that leads to good outcomes?”

On this day, DeVoll is meeting with a group of advisees to engage in a design-thinking exercise about the upcoming summer. The students generate ideas for summer projects both big (jobs, internships, study abroad, course work) and small (network with alums in your prospective field, shadow a professional). Next, they analyze to what degree they have the resources, desire, confidence and capability to pursue these projects and who can help them get there. Want to return to your lifeguarding job at the neighborhood pool? Great, DeVoll said. But maybe you can deepen your skills on the job or gain additional experience by volunteering a few hours at a local nonprofit.

“The goal here isn’t to lock you into a plan, but for you to think about what’s possible and to test-drive some options now to see what you like and don’t like,” DeVoll tells the group. “You didn’t choose if there were no choices.”

Like Smith, DeVoll also has noticed that today’s students arrive ready to talk careers. They are declaring their majors earlier and are curious about which majors lead to which careers.

“More so than millennials, young people are focused on having some certainties and crave clarity about their futures,” DeVoll said. “They grew up with so much uncertainty watching their parents go through the crash of 2008. They are asking earlier than prior generations of students where all of this is going.”

Faculty members — with their deep knowledge and vast networks — are uniquely equipped to answer that question.

“We have moved past the point of thinking, ‘Well, this is an issue for the Career Center,’” DeVoll said. “While the Career Center owns career planning, we need to be better partners. Faculty are starting to think hard about what that looks like.”

The Career Center will track career outcomes for students who participate in PACE and other first-year programs. But Wittman expects the benefits to extend beyond good jobs.

“If we can help students identify their skills and passions earlier, they will be able to choose classes and co-curricular activities that amplify and build on those strengths,” Wittman said. “By doing this more intentionally, we not only give them a head start on their career planning, we enrich their four years with us.”