Days are hot in Colombo, a dense city of historic temples, sprawling markets and imposing Colonial structures. But at night, the Sri Lankan capital comes alive.

“Everything cools down,” said Anu Samarajiva, a master’s candidate in architecture and urban design in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. “You can smell the trees, walk along the ocean. The parks are full of people.”

“Everything cools down,” said Anu Samarajiva, a master’s candidate in architecture and urban design in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. “You can smell the trees, walk along the ocean. The parks are full of people.”

Samarajiva was born in Colombo but raised in Columbus, Ohio, where her father taught telecommunications. Returning to Sri Lanka, for her last three years of high school, was a shock but also instructive. “There was a whole family network,” she said, as well as social and language barriers. “It was hard for me to navigate. I didn’t have the cultural currency.”

The experience left Samarajiva deeply attuned to the particularity of place and to the ways social networks shape our experience of the built environment. Last winter, those themes came together in First Class Meal, a speculative design proposal that won the international Urban SOS: Fair Share competition.

Created in collaboration with two classmates — Lanxi Zhang, a recent master’s graduate in landscape architecture and urban design, and Irum Javed, a master’s candidate in public health in the Brown School — First Class Meal investigated how mobile technology and the sharing economy might leverage shuttered Los Angeles post offices to improve food access and equality.

The idea sparked headlines from Business Insider and The Architect’s Newspaper to The Atlantic, Food & Wine and Smithsonian magazines. In the months since, the team has worked with engineering giant AECOM, as well as the Van Alen Institute and 100 Resilient Cities, to move from drawing board to implementation.

“If successful,” noted The Guardian (U.K.) newspaper, First Class Meal would “do more than just reinvigorate infrastructure. It would knock down the biggest stumbling block facing all the other food-security startups around the country and the globe: sustainable transport.”

Something tangible

Growing up in Ohio, Samarajiva drew and painted constantly. She also developed a curiosity about how social, political and economic systems impact individual lives. As an undergraduate at Reed College in Portland, she studied economic policy, then spent a year with AmeriCorps, working with low-income entrepreneurs.

That experience led her to The Lewin Group in Washington, D.C., where she helped state agencies and nonprofit organizations implement individual asset development accounts — a concept pioneered by the Brown School’s Michael Sherraden.

“It was interesting work,” Samarajiva said. “We facilitated conversations between the federal government and child support and domestic violence programs. Those programs were changing lives.

“But I was working at a remove,” she said. “There was a lot of client interaction and data analysis. I wanted a more tangible way to help people. I wanted to bring something to the table that was meaningful and specific.”

An architecture summer program at Berkeley suggested a new path. “I was interested in design, and in the process of how design gets made,” she said. She found herself arriving early each morning and working late into the night.

“And I thought, if something makes you feel that excited, you should go with it.”

The future they want

Arriving in St. Louis, Samarajiva was struck by how a metropolitan area of nearly 3 million people seems to atomize into small neighborhoods of widely varying health and stability.

“Urban designers talk about connectivity,” she said. “In St. Louis, we have pockets. Tower Grove, the Central West End, Fountain Park. … In the space of five blocks, there can be incredible income differentiation.”

Samarajiva was particularly intrigued by McRee Town, a long-beleaguered neighborhood just south of The Grove, where she volunteered with a nonprofit grocery. In the 1970s, McRee Town was sliced through by construction of Highway 44. Businesses left, crime rates soared, connections to surrounding communities were rendered impassible. In the early 2000s, another 240 homes were leveled.

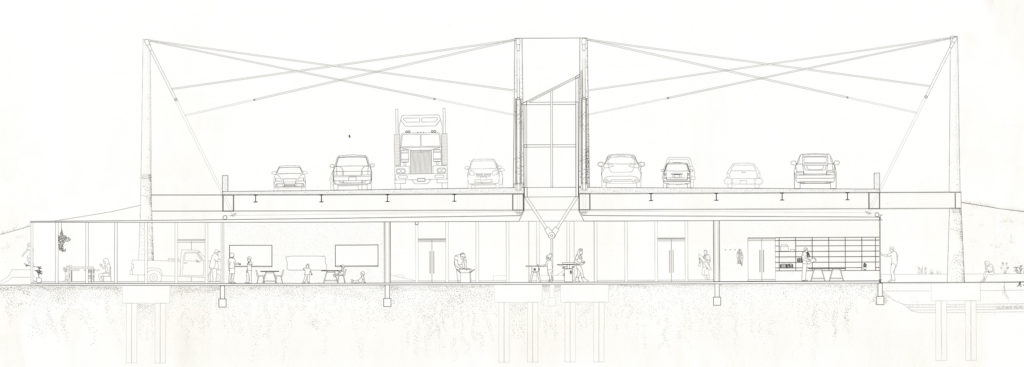

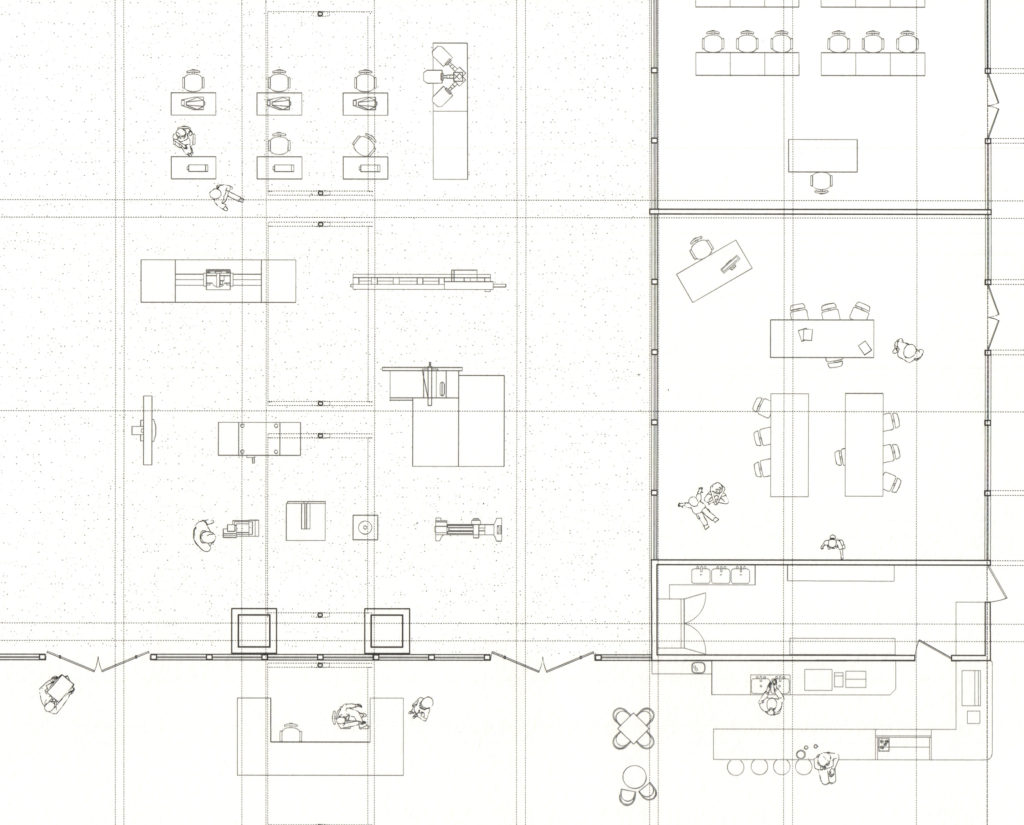

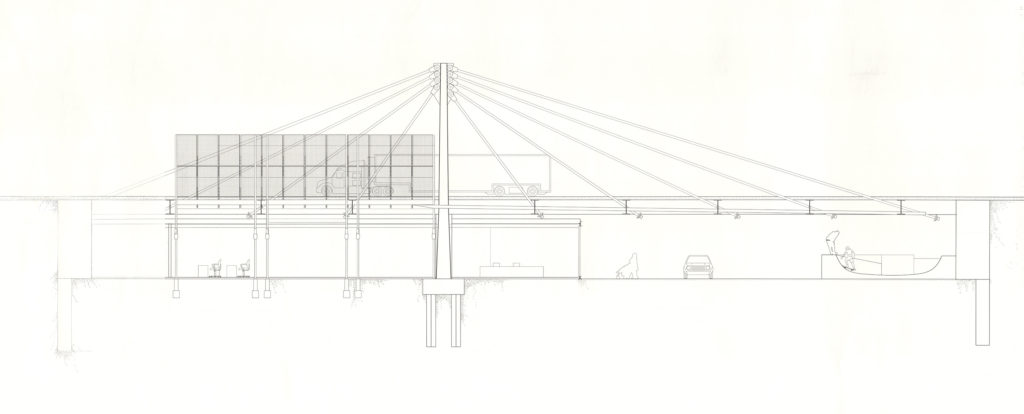

Yet today, infill development and historic renovation are bringing new life to McRee Town, which has been rebranded as Botanical Heights. For her thesis project, Samarajiva proposes building a community center beneath the highway, in a blocked underpass that remains emblematic of the neighborhood’s isolation.

“The idea is to reclaim that space,” she said. Rather than a barrier between neighborhoods, the underpass, which has been closed for decades, would become a point of convergence, offering workshops, classes and other services.

Before redevelopment, 46% of Botanical Heights residents were children, according to the U.S. Census. “This would provide resources to help them imagine, and enact, the future they want.”

Existing energy

In 2016, Samarajiva won a Sam Fox School travel grant to attend an urban design charrette in Havana, Cuba. A sort of architectural brainstorming session, the event brought together an array of international architects, planners, artists and developers.

But the real lessons came from the city itself. For example, Samarajiva was struck by the ubiquitous carros particulares, an informal ride-sharing network that supplements Havana’s meager public transportation — and which, in the age of Uber, also seems startlingly prescient.

“The system is very cheap and it works really well,” she said. As an architect, “you want to channel that energy, rather than simply impose your design. How can I augment what’s already here?”

This summer, Samarajiva will travel to Johannesburg, as part of the Sam Fox School’s Global Urbanism Studio. Meanwhile, the First Class Meal team, working with faculty advisor Linda C. Samuels, assistant professor of architecture, has confirmed partnerships with Los Angeles nonprofits Food Forward and LA Kitchen, and discussed the project with representatives from Uber and Amazon Fresh. They’re also continuing to work with AECOM and city officials to identify potential sites and define space requirements.

“In studio, we rarely get to this level of detail,” Samarajiva said. “Implementation is difficult — there’s a rigor and specificity to it. But you also learn to adapt and figure things out.”

“I’m really interested in how people make decisions,” she said. “There’s a lot of depth behind why people do what they do. There are reasons things are the way they are.”

But as an architect and urban designer, “I now have a skill set that can help people think about alternatives.

“I have a way of visualizing the future and showing people what it might look like.”