Comics have long flown beneath the scholarly radar. But recent years have brought new attention, and increasing sophistication, to the academic analysis of comics and cartooning.

In 2014, Rebecca Wanzo, associate professor of women, gender and sexuality studies in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, and associate director of the Center for the Humanities, became a founding board member of the Comics Studies Society (CSS), the first professional organization for comics researchers in the United States. Wanzo also serves on the editorial board for Inks, the CSS journal, which will debut later this year. She recently contributed to “The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art,” which won the 2016 Eisner Award (the “Oscars of comics”) for Best Academic/ Scholarly Work; and to the feminist sci-fi comic “Bitch Planet.”

We sat down to discuss comics, culture and the CSS.

You didn’t read comics until graduate school. What drew you to them?

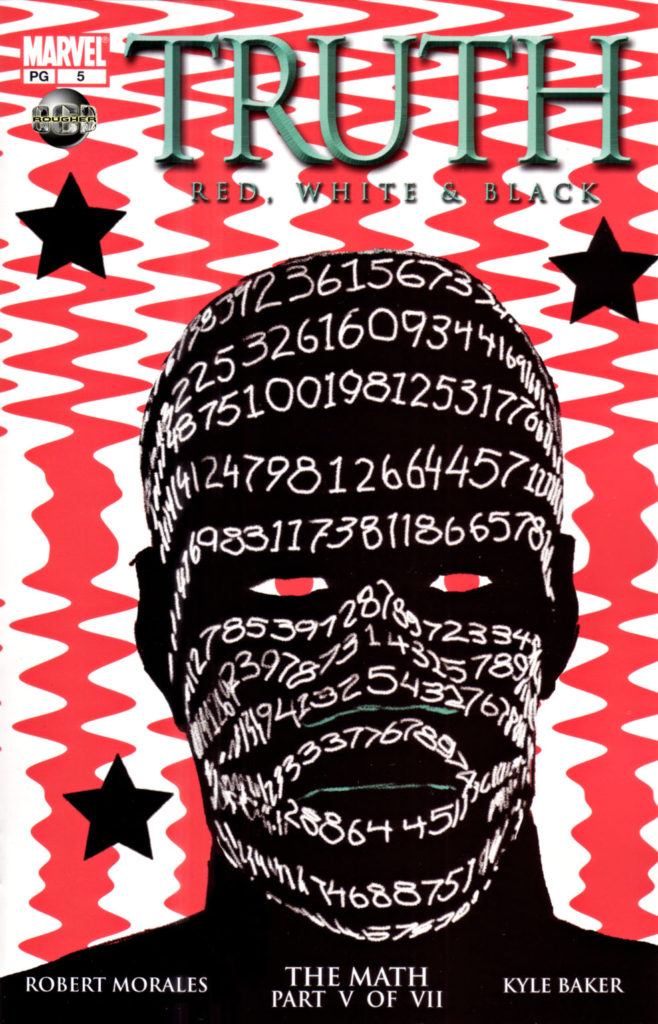

When I was studying for my exams, I was reading a novel a day, and no longer had time to read for pleasure. So I started Neil Gaiman’s “Sandman,” then “Preacher,” then “Truth: Red, White & Black,” which was a black version of Captain America. That became the subject of my first comics article and the inspiration for my current book project, “The Content of Our Caricature.”

Many comics scholars arrive through fandom. Does a more traditional academic background provide greater critical distance?

I don’t think so. There are debates about fan studies and whether fans can be rigorous scholars. But people who study high texts — Shakespeare, T.S. Eliot, Toni Morrison — also have deep attachments.

I do think scholars of popular culture have a heightened sense of the need to defend their subjects. In some ways, it’s similar to black studies — which is why I’m interested in the nexus between African-American studies and fan studies. Certain kinds of fandom are like political commitments.

Your first book, “The Suffering Will Not Be Televised” (2009), examined sentimental storytelling and the question of which victims get to “count,” culturally speaking. How do those themes connect to your comics work?

I’m interested in the relationship between representation and political discourse, and in the idea that things we read or see inspire us to action. People criticize the sentimental, but it’s hard to name a social justice project that hasn’t depended on sentimentality to do its work.

Part of what’s interesting about comics is the way different genres embody different models of citizenship. Newspaper comics are filled with children and families; superheroes represent a kind of ideal citizen/soldier; comics biographies and autobiographies tend to focus on heroic individuals. I wanted to think about how African-Americans fit into all that — particularly within this medium, with its history of caricature and excess.

The issue of caricature seems particularly fraught.

Think about Charlie Brown, the way he’s drawn. The body is a sign. Comics depend on this language of exaggeration and excess. But it’s really easy for representations of black people to slip into racist caricature. How do you get away from caricature in a medium built upon it?

But what’s more interesting to me is when black comic artists intentionally use caricature, and to what ends. Sam Milai, the great Pittsburgh Courier editorial cartoonist, whose archives are in the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum (where Wanzo is a board member) had a gorgeous, realist phenotype for black people he thought were doing good things, but sometimes used racist caricature for people he was criticizing. You see this consistently in black cartooning.

What was the impetus behind forming the Comics Studies Society?

Comics is an unusual field. It’s very connected to creators, and a lot of people with deep knowledge and expertise aren’t necessarily academics. At the same time, academics who study comics usually began, and did dissertations, in other fields. Few universities have dedicated positions for comics scholars.

We want the CSS to welcome comics writers and reviewers, as well as academics, but also to build prestige and to serve as a benchmark for the field. A lot of people teaching comics still don’t really know what to do with them. They try to approach comics like novels — which is why the phrase “graphic novel” has such currency, even when we’re really talking about graphic memoir, comic strips or single-issue comics.

Are there particular works you like to teach?

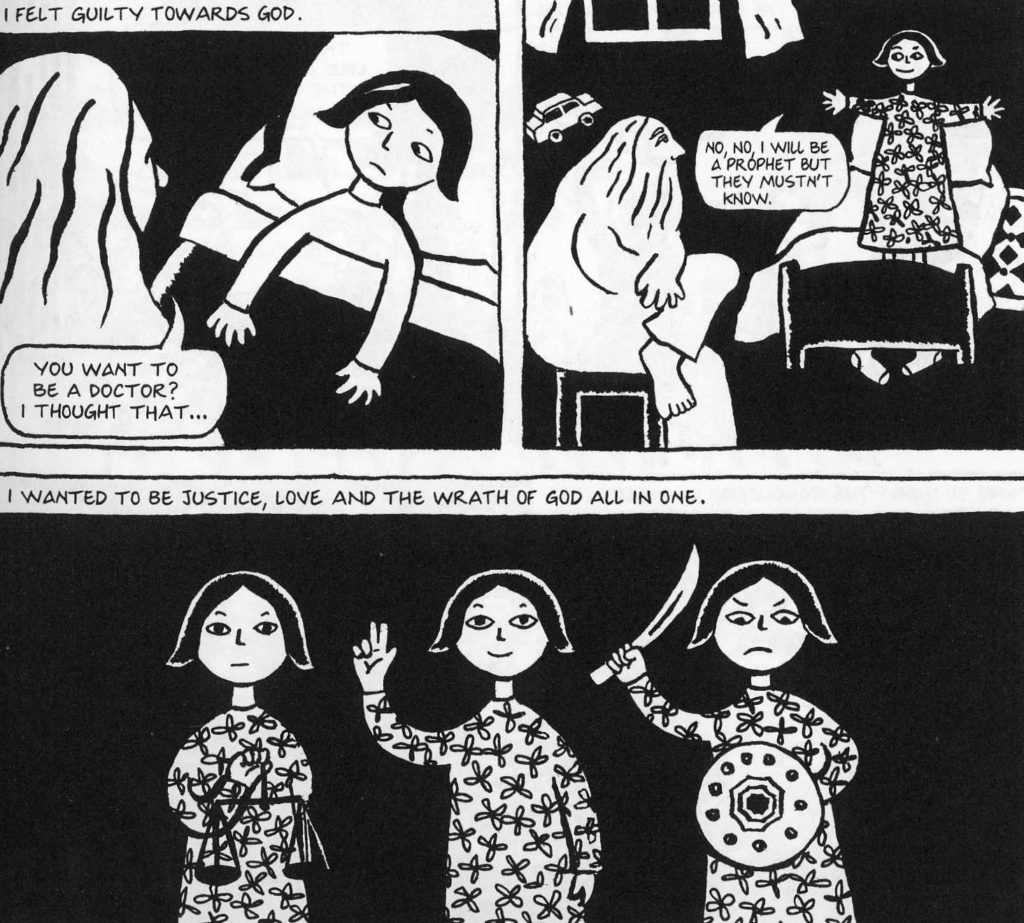

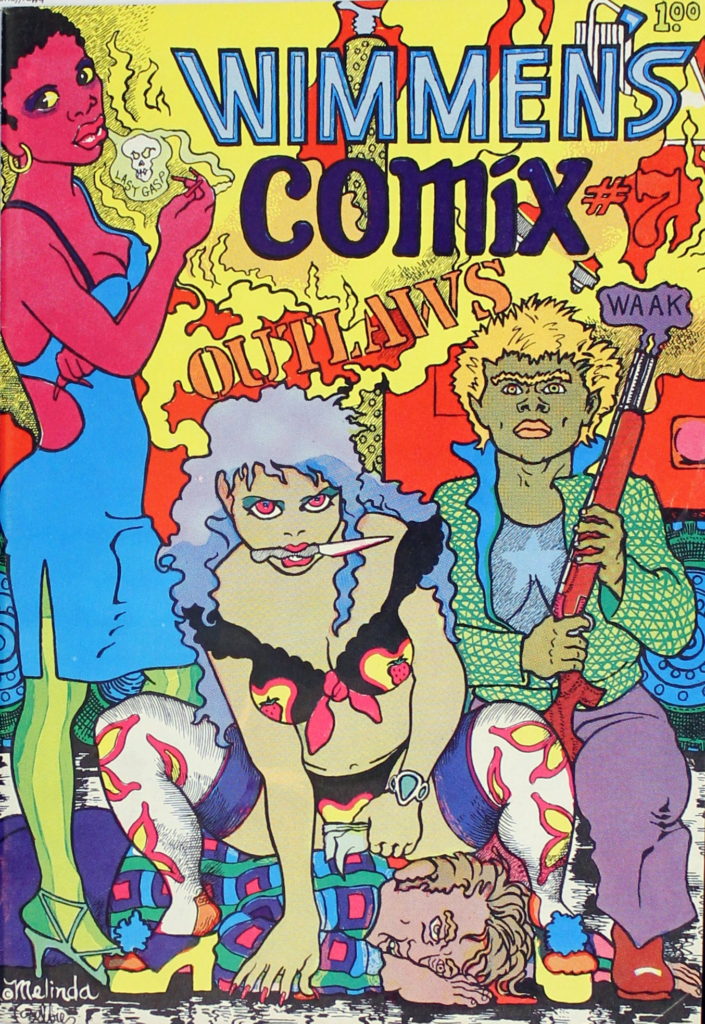

I’m teaching a first-year seminar, “Sex and Gender in the Gutter,” which introduces gender and sexuality studies through comics. We do some usual suspects, like “Persepolis” and “Fun Home.” I enjoy teaching excerpts from “Winmen’s Comix,” especially the early issues, which are really transgressive. Students assume representation gets more progressive over time, but that’s not necessarily true. For feminists, the 1970s were pretty radical!

I like teaching “American Born Chinese” and “Truth: Red, White and Black.” But “like” is a funny word … I think it can be interesting to teach people like Robert Crumb, even the really racist stuff, and Chester Brown. I remember the class splitting over “Paying For It,” Brown’s manifesto about prostitution. On the second day, the women and men had literally moved to different sides of the room. I’d never seen anything quite like it.

We touched on caricature, but are there other formal elements that define comics language? What can comics do that other media can’t?

That’s the constant debate. And you have to be careful with it. … Anytime you say “this only happens in comics,” you set yourself up for a fall. Certainly, caricature happens in other media. Sometimes the questions we ask of comics bring us back to the realm of the defensive.

But there are things that comics, as a medium, does in interesting ways, in terms of narrative and temporality. Students often have to shift how they read. They assume they can read quickly — “oh, it’s just comics!” — but then realize they’re missing things and have to slow down. How does the eye move? How long do you dwell on a particular image? What kind of interaction does that require?

In film, you can’t get away from the idea of movement. But in comics, you have to decide to turn the page.