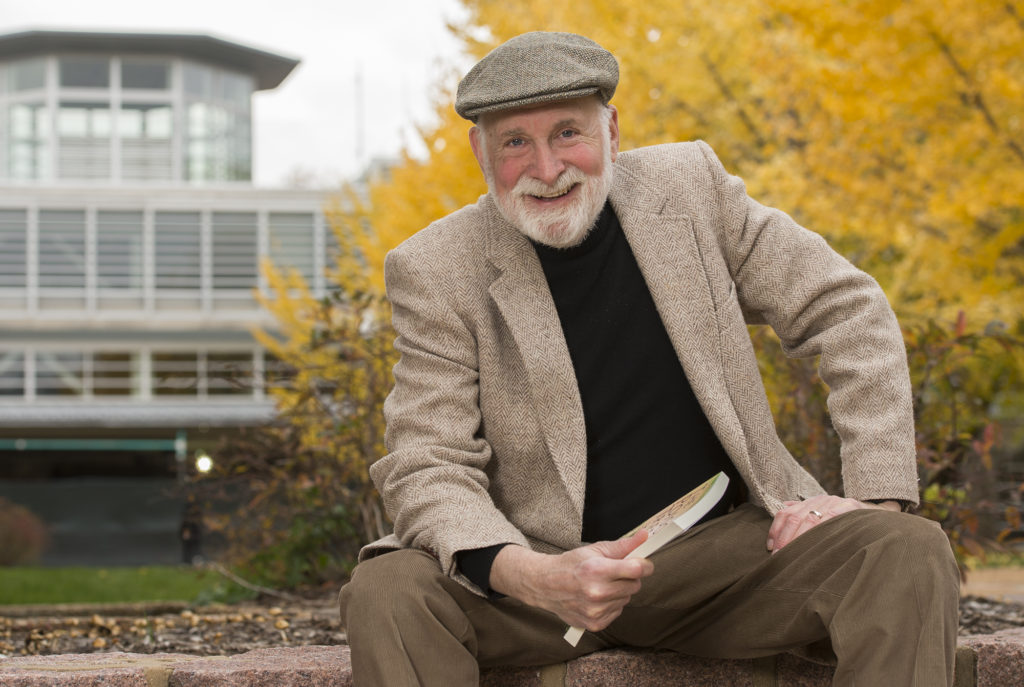

Henry Schvey is a go-to guy in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, for so many reasons.

He’s a steadfast presence in the Performing Arts Department (PAD), having directed more than 25 plays in his nearly 30-year tenure at the university. He has written, lectured and taught extensively on modern drama. He’s the resident expert on iconic writer Tennessee Williams, particularly on Williams’ time at Washington University. And anything you want to know about Oskar Kokoschka, the Austrian expressionist painter, Schvey’s your man.

He’s a prolific writer, playwright, poet, director, teacher, mentor — the embodiment of a liberal arts professor at a major American university. He’s also a husband, father, grandfather, colleague and friend.

And on the day after the most contentious presidential election in modern history, Schvey greeted a visitor to his office in the Mallinckrodt Center with a smile, saying, “I’d rather talk baseball.”

“The first thing I said after learning the result, almost to myself, not aloud, was ‘wait for spring training,’ ” said Schvey, a native New Yorker who is an ardent fan of the St. Louis Cardinals. “We need that.”

Schvey has made a career on knowing what’s needed at the right time, from his arrival at Washington University in 1987 from the Netherlands’ Leiden University as chair of the PAD, to now. He performs multiple roles these days as professor of drama and of comparative literature in Arts & Sciences and as a director, including his current PAD project, “Macbeth,” which has been cast and will be performed in February.

He’s also teaching an upper-level course on Shakespearean tragedy, as well as a course to first-year students called “What is Art?” Moreover, he just published his latest work, “The Poison Tree,” a memoir of growing up in New York City in the 1950s and ’60s as the son of a domineering, abusive father — a powerful and highly respected executive for Merrill Lynch — and a mentally ill mother.

And if he wants to first talk baseball — a balm for Schvey even if a new world order has the Chicago Cubs as reigning champions — so be it.

Showing — instead of telling

But it’s “The Poison Tree” that’s chief among talking points, a work that begins — and ends — in New York, and in between is a story of finding lifelong love with his wife, Patty, and with that, the family that was so elusive to him growing up. The book is intensely personal yet universally appealing, a story of survival when sometimes the biggest barriers to growth are the very people who brought us into this world.

It’s a work, Schvey said, that he began writing in 2007, just after stepping down as chair of PAD after 20 years, and finding himself with more time to work on projects — and to reflect. Several times, he said, he thought he was finished with the book until he started the valuable process called workshopping, everywhere from Washington University’s own Summer Writers Institute to workshops in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., to Yale University and beyond.

“One of the things that came out of the workshops is in the telling of a personal story like this, you ask yourself, ‘Why isn’t it just enough to write it, and have it on the computer and show it to a few friends and your children?’” Schvey said. “But for me, because of what the work was about, it was important that it not be a vanity project, or even a cathartic project alone.

“I wanted to feel like it was saying something that was more than about me.”

The writing was a journey that took years to finish, because, Schvey said, he needed to be fair to the characters. “I didn’t want it to be simply something that was revelatory or gossipy or negative. I wanted to make sure that I was being as objective as I could be to the kind of mystery that my father represented to me.

“The more I worked on it, the more I felt in touch with him. He didn’t need my forgiveness. But there was that aspect of a kind of closeness that I never felt in life. But I felt it through the writing process.”

So he wrote, and rewrote, and rewrote again, over the course of nine years. The professor as student, showing, instead of telling, how to write a memoir. It’s a process from which he said he has learned a great deal.

“It has made me aware of storytelling,” he said. “Drama is storytelling, and fiction is storytelling, and memoir is storytelling — effectively and economically.

“Directing is also storytelling. So much art is about telling a story. But it’s not the content, it’s the form. In that sense, writing nonfiction is just like writing fiction. You have to draw the reader in — there is a craft element.”

Circling back

Schvey will continue to work on that craft. His next book is about Williams — for Schvey, it somehow always circles back to Tennessee Williams — and the little-known fact that the writer painted, at “a feverish pitch” in the last decade of his life. “It’s not only about Williams’ own paintings, it’s about how the visual arts entered his world,” he said. “It incorporates allusions to painters and paintings, and also the stage directions of his plays.”

Writing, for Williams, was all about his family and family relationships, Schvey said in a lecture in 2011. “For any writer, the bars of the prison are just as important as the free space outside,” he said.

Schvey welcomes the link between Williams and the process of writing “The Poison Tree.”

“I was drawn to Tennessee Williams from the very beginning because I sensed an emotional connection,” Schvey said. “The first play I looked at was ‘The Glass Menagerie.’ His early rebellion against a domineering mother, and his need to leave his home and become an artist.

“So much of his writing spoke to me very directly,” Schvey said.

It’s a now-famous story of Schvey’s, of him in 2004 in a New Orleans bookstore finding a blue examination booklet of Tennessee Williams. On a back page, a forgotten poem titled “Blue Song,” which eventually would be published in The New Yorker in 2006. It’s a poem, written in a test booklet at Washington University in 1937, about an aimless young man and his desire to find his place. Its last line: “Let the wind have it and it will find its way home.”

Winds have blown Henry Schvey every which way, too, but he found his way home. And it’s right here.