Roman military hospitals, knows as valetudinarian, wrapped small patient rooms around a central courtyard. A similar design can be found in the ruins of Mihintale, a 9th-century Sri Lankan complex.

Replace the courtyard with a nurses’ station, and the floor plan might be that of a contemporary emergency department.

For all the advances of modern medicine, health-care architecture — to a startling degree — has remained guided by custom and intuition rather than research and testing. Yet over the last decade, an emerging field known as evidence-based design has begun to rigorously appraise the relationship between the built environment and patient outcomes.

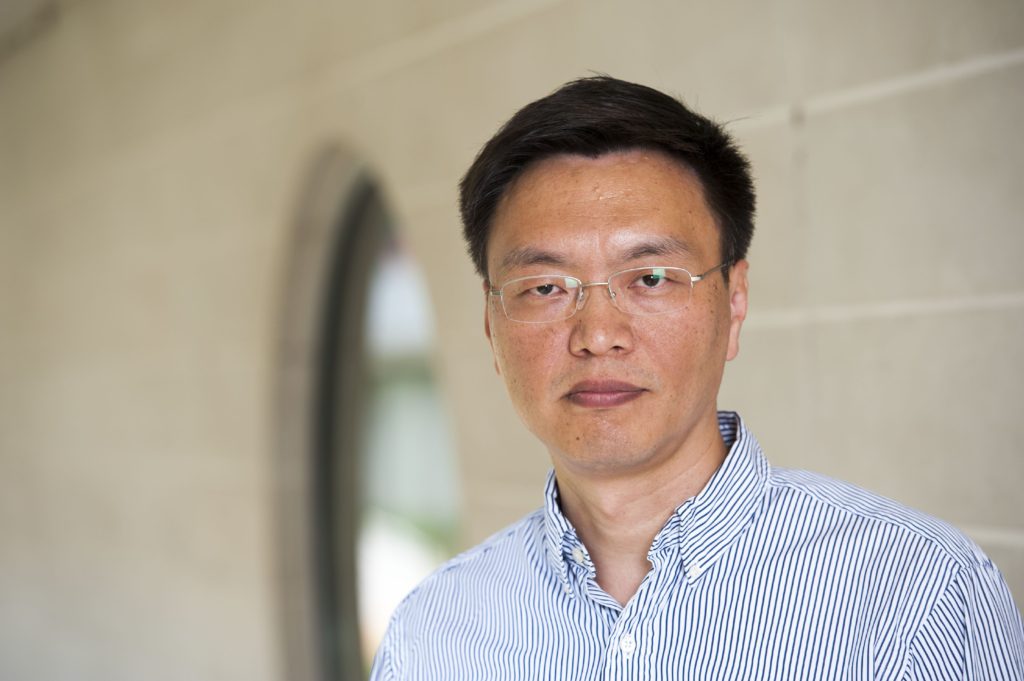

“These are inherently interdisciplinary problems,” said Xiaobo Quan, a leading scholar in the field. “The built environment impacts behavior, as well as energy efficiency and other aspects of building performance. But behavior is also shaped by education, operations and the culture of an organization.

“To truly understand the role of design,” Quan added, “you need a broad perspective.”

Sharing knowledge

Last month, Quan joined the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis as director of its new Center for Health Research & Design (CHRD).

Part of a growing national trend for evidence-based research in architecture, the CHRD, in collaboration with BJC HealthCare, is launching with three projects. In addition, the center has partnered with the Brown School to gain membership in the AIA Design & Health Research Consortium. The group, formed in December 2014 by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), aims to promote basic research about design and public health, and now includes 17 academic partners, Washington University among them.

“Design for health is an important and pressing issue in architecture today,” said Bruce Lindsey, dean of the Sam Fox School’s College of Architecture and Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design, and president of the ACSA. “Over the next decade, billions will be spent updating and replacing aging infrastructure. Evidence-based design has the potential to transform the delivery and experience of care from the community to the hospital and back.

“In St. Louis, we have an incredible confluence of resources,” said Lindsey, who also serves as the E. Desmond Lee Professor for Community Collaboration. These include Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the university’s Institute for Public Health, as well as the area’s major health-care providers and a pool of significant architectural firms that are active in health-care design. “It’s a combination few other cities can match.”

“There’s a growing passion around these issues,” Lindsey added. He said that, thanks in part to researchers like Quan, “I think we’re all beginning to understand the importance of collecting the knowledge gained through the design of individual buildings — and of sharing that knowledge across the spectrum of clients and practitioners.”

A paradigm shift

Quan comes to the Sam Fox School from The Center for Health Design in Concord, Calif., where he served as a senior researcher. He previously studied health-care environments for the Karlsberger Companies, and was an architect for the East China Architectural Design & Research Institute and for the Shanghai Xian Dai Architectural Design Group.

“It’s been a long journey,” Quan said. “Evidence-based design is still an emerging field —there are a lot of gaps in our knowledge.” Yet its principles are already reshaping how architects approach the design of hospitals, health-care clinics and other environments that impact human health. “This is just the beginning.”

For example, Quan’s doctoral thesis — which he completed at Texas A&M University in 2006 — investigated how patient room design can affect both hand-washing compliance and family visitation. Compared to an open-bay intensive care unit, Quan found that a well-designed private room (in which sinks and gel dispensers are located by the entrance) can significantly increase hand washing and subsequently patient outcomes.

At the same time, “Having more space at the bedside impacts how long visitors stay,” he said. This in turn affects a patient’s experience, sense of social support and ultimately health outcomes.

The dynamic is subtle but measurable — and anticipated important aspects of the Affordable Care Act. Under the new law, patient satisfaction is one of several key factors, along with safety, efficiency and clinical outcomes, used to determine reimbursement rates.

“Patient experience is becoming more and more important,” Quan said. “We need to better understand the role the physical environment can play.”

Critical mass

In 2004 and 2008, Quan co-authored two large-scale reviews of health-care environment research literature, which synthesized evidence from multidisciplinary research on the physical environment’s impact on health-care outcomes. Those reviews found that the increased costs of better environments are quickly recouped through shorter stays, reduced infection rates and higher operating efficiencies.

More recently, Quan has explored topics such as ambulatory care environments for population health; patient room design; the safety of patient and health-care staff; green cleaning in health care; and how environmental strategies can improve the experience of pediatric radiography.

Meanwhile, evidence-based design has begun approaching something like critical mass. A decade ago, researchers fought to publish findings in medical or psychological journals. Today, the field boasts dedicated publications, conferences and professional networks.

“We have a real opportunity here,” Quan said. By fostering collaboration amongst academic researchers, medical professionals and architectural practitioners, the CHRD and similar initiatives can “organize research in this field and promote the creation of new knowledge.”

At the Sam Fox School, Quan — who also serves as a professor of practice — is launching a three-year investigation of ambulatory care centers. Such facilities are growing at much faster rates than traditional hospitals, he explained, thanks in part to the Affordable Care Act’s emphasis on outpatient surgical procedures.

“We’re looking at the whole journey,” Quan said. “Where are these facilities located? How do patients go from arrival to surgery to discharge to home? What are the key moments, and what role does the physical environment have to play?”

Other projects of the CHRD will include an assessment of open office standards for health-care environments, led by Catalina Freixas, assistant professor of architecture, with Arye Nehorai, the Eugene & Martha Lohman Professor of Electrical Engineering in the School of Engineering & Applied Science. Valerie Greer, professor of practice in architecture, will lead a multidisciplinary team in examining current inpatient practices and the future of the patient room.

“It’s a complicated typology,” said Emily Johnson, a Master of Science in Advanced Architectural Design student who is working with Greer, and who has researched the history of the St. Louis Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center. To properly design a room, “you have to understand medical equipment and how different treatment options affect patients. You have to know enough to predict what’s going to be needed, as well as where and when.

“You have to really know the hospital.”

About BJC HealthCare

BJC HealthCare is one of the largest nonprofit health-care organizations in the United States, delivering services to residents primarily in the greater St. Louis, southern Illinois and mid-Missouri regions. BJC’s nationally recognized academic hospitals, Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, are affiliated with Washington University School of Medicine.

About the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts