Everyone would rather cook than take out the garbage. Perhaps that’s why biochemists learned how cells make proteins 70 years ago, but are just now learning how they get rid of proteins that are no longer needed or no longer work.

Cells have two cellular disposal systems, said Richard Vierstra, the George and Charmaine Mallinckrodt Professor at Washington University in St. Louis. One (the proteasome, or protein-eating body) is rather like a garbage disposal and the other (the autophageosome, or self-eating body), which handles bigger messes, is more like the bin liner for a trash can.

Proteasomes are typically selective, whereas autophagy has generally been thought to be indiscriminate. But Vierstra and his colleague Richard Marshall, research scientist in the Department of Biology in Arts & Sciences, have demonstrated that autophagy — under conditions other than cell starvation — is also carefully regulated.

In 2015, they showed that a collection of tags and bridging receptors controls what goes into the bin liners in the model plant Arabidopsis. Marshall then decided to “make a little foray into yeast,” to see whether the autophagy pathway is conserved outside of the plant kingdom.

In the July 29 issue of Cell Reports, they report that the same pathway exists in yeast and probably in humans, although the bridging receptors are different in each organism.

Importantly, this pathway is implicated in a variety of neural pathologies, such as Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease and ALS. In each of these diseases, cells sequester broken proteins into aggregates, which they are then unable to clear, to the detriment of the cells.

In doing this work, the scientists devised a simple assay that enables them to quickly dissect the autophagy pathway and identify its regulatory components. This assay, they suggest, offers a way to learn more about what goes wrong in the aggregation-prone pathologies.

A smart garbage disposal

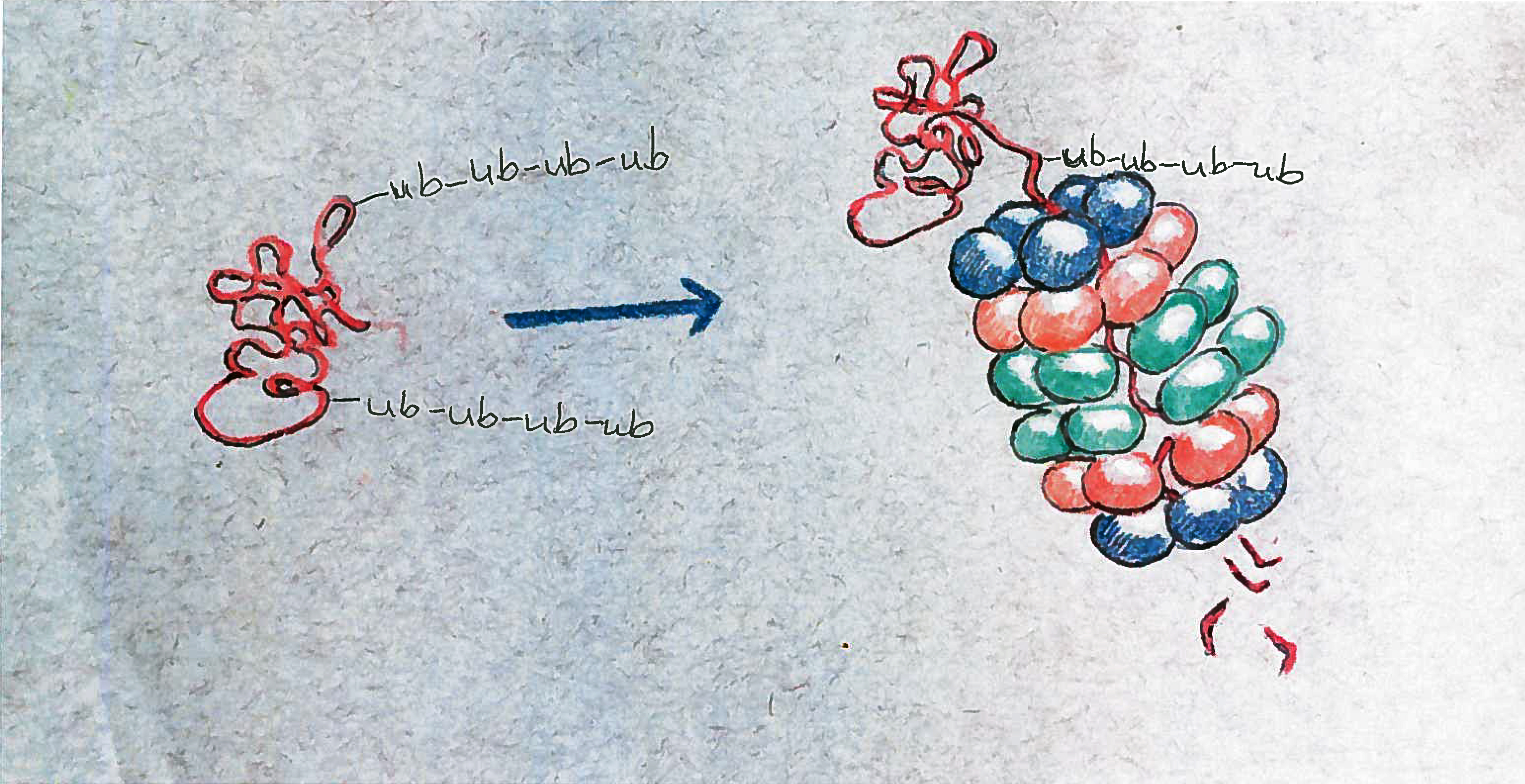

Thousands of enzymes roam the cell looking for unwanted or broken proteins, Vierstra said. When they find one, they tag it with a marker protein called ubiquitin. Proteins bearing ubiquitin chains then are delivered to one of the 30,000 proteasomes in the cell.

If the ubiquitin chains dock with receptors on top of the proteasome, the protein is unfolded, and threaded through the orifice of the proteasome like a strand of spaghetti. Active proteases within the barrel then chop the long protein chain into smaller pieces that can be re-used.

A smart bin liner

The cell needs a second system, Vierstra said, because many proteins are in very large complexes. How do you get rid of the big stuff, he asked, when the proteasome has such a small orifice?

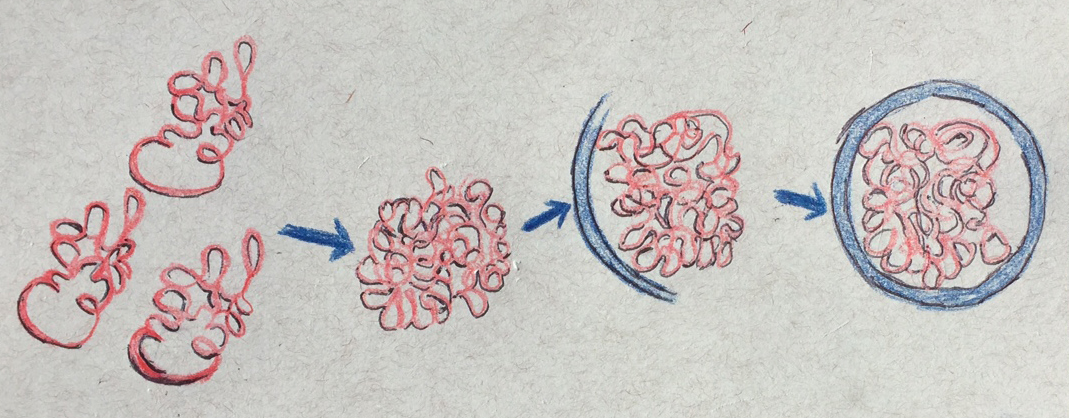

That’s where autophagy takes over. In this process, the cell assembles a double-walled cup-shaped vesicle that envelops the “garbage,” closes to form a sac, and then fuses with a sac of enzymes (a vacuole or lysosome) that then breaks down the garbage together with the sac.

The scientists tested autophagy by deliberately poisoning proteasomes and watching how they were discarded. But the cell also uses autophagy to remove large protein complexes other than proteasomes, whole organelles, such as mitochondria and even pathogens, such as bacteria.

In 2015, Marshall and Vierstra showed that if they killed proteasomes in Arabidopsis cells, the proteosomes were quickly decorated with ubiquitin chains, and then targeted for autophagy by a bridging receptor that binds both the ubiquitin chains and a surface protein that lines the autophagic membrane, thus tethering the proteasome to the membrane.

In Arabidopsis, this tethering protein is called RPN10. Yeast has only a truncated form of RPN10, so Marshall was curious to see whether the pathway exists in yeast as well. He found that it does, although the tethering protein is a different one called Cue5.

The connection to human disease

The abnormal protein that damages brain cells in Huntington’s disease also has a ubiquitin-binding domain called a CUE domain.

Alert to connection, Marshall decided to track the proteasomes after they were killed but before they were dumped. When he did this, he discovered that they clumped first.

Cells sort malfunctioning proteins into two different aggregation spots, or protein graveyards, called JUNQ and IPOD, Vierstra said. The sequestration of a protein in JUNQ is reversible, but IPOD proteins are never rescued.

Proteins are steered to one or another aggregation spot by molecular “chaperones.”

“We knew from the literature that formation of IPOD aggregations required a molecular chaperone called Hsp42,” Vierstra said. “It turned out that proteasome aggregation also requires Hsp42.

“Hsp42 somehow senses that a proteasome is ‘dead,’ and helps sort it into an aggregate, where an enzyme covers it with ubiquitin. The ubiquitin is then recognized by the Cue5 receptor, which tethers it to the autophagy membrane,” Vierstra said.

Together, Cue5 and Hsp42 provide an important surveillance mechanism in yeast (and likely animals) that is central to maintain a healthy pool of active proteasomes, the scientists said.

Fluorescing green

In the long term, the value of the research may lie less in the discovery of the Cue5 receptor and Hsp42 chaperone than in the creation of an assay that can be used to understand what goes wrong with autophagy in aggregation-prone diseases.

“These pathologies are difficult to study because they’re challenging to trigger in reproducible manner,” Vierstra said. “But it turns out that we can trigger proteasome aggregation just by adding a drug that kills proteasomes and start the process quickly.”

In the assay, the proteasome are tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP), which makes it possible to see where they go, Vierstra explained. When the autophagic system eats a protein that is tagged with GFP, the protein disappears, but the GFP stays around. So the accumulation of free GFP serves as a surrogate for autophagy.

It is this assay that allowed Marshall to quickly find the Cue5 receptor. “We tested every known autophagy receptor knock-out in the books,” Vierstra said. In each case, free GFP appeared in the yeast vacuole, indicating that the missing receptor didn’t prevent the proteasome from being broken up. Only in the case of the Cue5 knock-out was free GFP missing.”