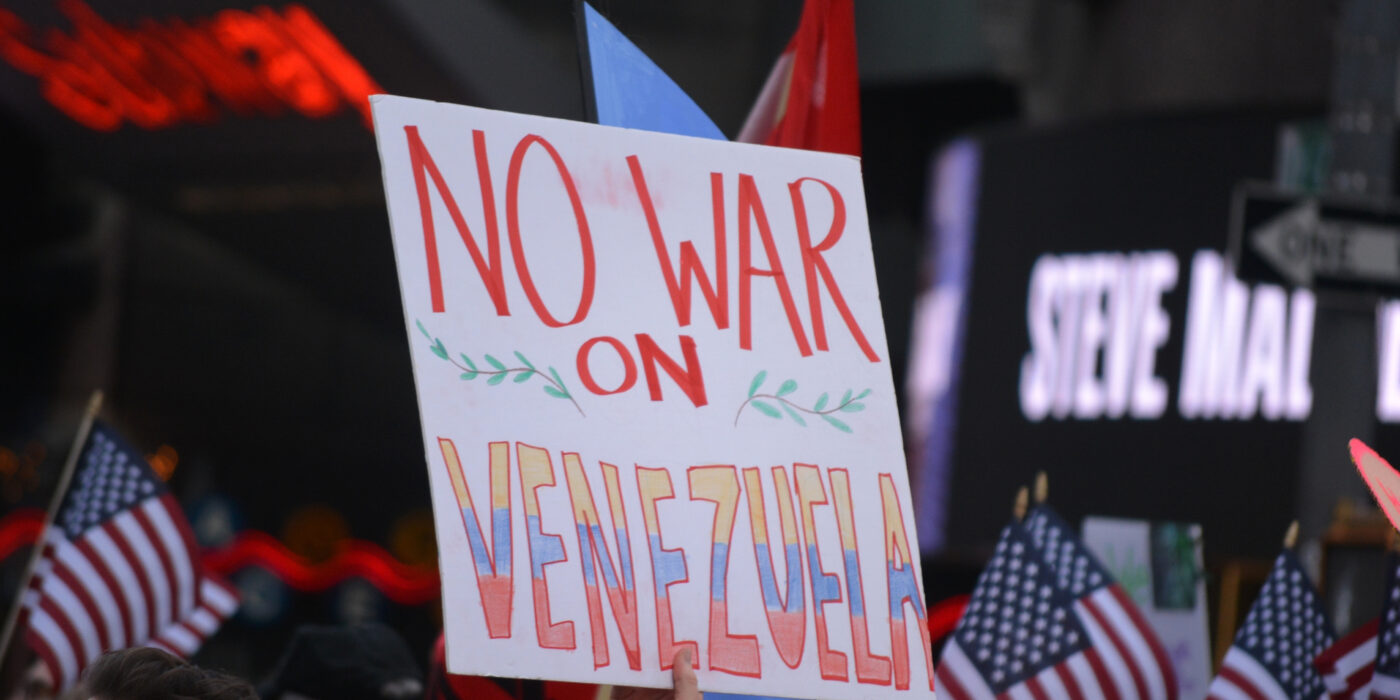

President Donald Trump’s use of unilateral action in Venezuela is unpopular with Americans, even his base, according to early polling. Will that be enough to rein in the administration when other branches of the government cannot or will not?

The Founding Fathers created formal checks and balances to ensure no branch of the government became too powerful. But one of the most powerful checks on presidents’ unilateral power in modern times has been public opinion, according to Dino P. Christenson, a professor of political science in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

In the book “The Myth of the Imperial Presidency: How Public Opinion Checks the Unilateral Executive” (University of Chicago Press, 2020), Christenson and co-author Douglas L. Kriner contend that institutional constraints on the unilateral presidency are weak. Congress can overturn presidential actions by law, but that requires a veto-proof two-thirds majority in both chambers — something that’s extremely unlikely in modern times. Likewise, the U.S. Supreme Court can strike down an executive order as unconstitutional, but most are carefully crafted to avoid raising concerns of constitutionality — particularly on foreign policy, where the presidency has garnered more power and flexibility.

But that doesn’t mean that there are no constraints on the executive branch.

‘Few members of the GOP are willing to publicly break with President Trump. … This suggests a context in which the historically powerful informal check of public opinion on unilateralism has given way. Increasingly the only check on unilateral action can be at the ballot box.’

Dino P. Christenson

“The myth of the imperial presidency is that those limited formal constraints are the only constraints on unilateral action. Instead, we argue that there are informal constraints — or at least there have been,” Christenson said.

“The public has constrained prior presidents’ use of unilateral action through their overall support for the president and their policy agendas. Presidents, with concern for their legacies as well as their parties’ policy agendas and electoral fortunes, generally feel emboldened when the wind of public opinion is at their backs and restrained otherwise.”

In the past, members of Congress have successfully leveraged public opposition to constrain unilateral actions. However, we have entered a new era of polarization, he said.

“Few members of the GOP are willing to publicly break with President Trump, be it on separation of powers or policies,” Christenson said. “We also have a president who is less attuned to out-partisans and independents. In all, this suggests a context in which the historically powerful informal check of public opinion on unilateralism has given way. Increasingly, the only check on unilateral action can be at the ballot box.”

Foreign policy unlikely to have lasting impact on approval rating

One year into his second term, President Trump’s approval rating has dropped, but it’s nothing unordinary — at least at this time, Christenson explained.

“Despite the struggling economy and high inflation, draconian immigration actions, executive overreach — particularly the politicization of the DOJ and capturing (Venezuelan President Nicolás) Maduro without congressional authorization — the numbers here are very much in line with historical patterns,” Christenson said.

“Thus, his support in his first year seems to be less about any single event or issue, and more of a standard downward trend — by modern standards — that we see across presidents as they respond to a host of issues and events.”

Proving that point, Christenson noted that Trump’s first-year approval for both his first and second terms was nearly the same. Trump’s approval rating started a bit lower this time, but it fell at a similar pace.

Another trend that is becoming more common in this era of polarization is the kind of movement — or lack thereof — among partisan identifiers. When approval ratings drop nowadays, the bulk of movement is among the president’s party and independents, Christenson said.

“If you look at Trump’s polls by party, the movement is almost exclusively among independents, and a bit among Republican Party identifiers, too. Democrats have been bottomed out since the beginning of this term, and I don’t expect that to change anytime soon, if ever. Independents have shown a steady decline over the year — and now a bit lower than usual. Presidential party identifiers seem to be moving toward the 80-90% range on approval, not unlike what we saw with (former President Joe) Biden’s approval among Democrats.

“Thus, by historical standards, the GOP in the masses has not fractured much. If there is something unusual about public support for President Trump in his first year, it is how standard they seem to be given the events and issues of 2025,” he said.

While many Americans are unhappy with Trump’s actions in Venezuela and threats to Greenland, Cuba, Colombia and Mexico, Christenson predicts that recent events will not have a lasting impact on his approval rating.

“The economy would have to crash — or at least further deteriorate — and inflation remain high over the next year for the public approval among independents and Republicans to sink further,” Christenson predicted. “I don’t see foreign policy as causing a permanent drop in his approval among his base or independents, unless, of course, the president puts boots on the ground in Venezuela or elsewhere.”