Hepatitis C, a bloodborne virus that damages the liver, can cause cirrhosis, liver cancer, liver failure and death if left untreated. Despite the availability of highly effective treatments, the prevalence of hepatitis C infection remains high, particularly among women of childbearing age, who account for more than one-fifth of chronic hepatitis C infections globally. Within this group, new mothers are especially vulnerable because treatment has traditionally required outpatient follow-up appointments during the challenging postpartum period.

Now, a new study on an innovative clinical program developed by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that giving postpartum mothers with hepatitis C the opportunity to start antiviral treatment while they are still in the hospital after giving birth, and bringing treatment to bedside prior to discharge, significantly increases their odds of completing the therapy and being cured. The authors found that new mothers who saw an infectious disease specialist and received medication for hepatitis C during their hospital stay were twice as likely to be cured compared with mothers who got a referral to an outpatient follow-up appointment.

The findings appear Sept. 11 in Obstetrics & Gynecology Open.

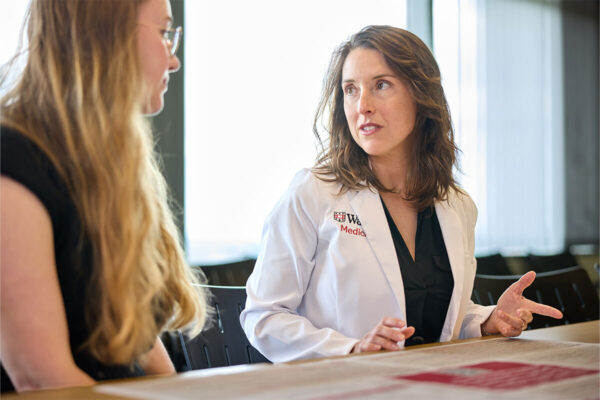

“We were seeing too many patients fall through the cracks simply because of traditional divisions between what was treated inpatient — labor and delivery — versus outpatient — hepatitis C,” said Laura Marks, MD, PhD, senior author on the study and an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the John T. Milliken Department of Medicine. “We partnered across departments to make sure that when pregnant patients come to Barnes-Jewish Hospital to deliver their babies, they have the option to also get care for a disease that, if left untreated, can lead to cancer.”

Breaking the cycle

Patients are often diagnosed with hepatitis C as part of routine screenings during pregnancy, but treatment has historically been deferred to the postpartum period. However, once women give birth, they don’t always return for follow-up care to start the medication.

To break the cycle, Marks, in collaboration with Jeannie Kelly, MD, an associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology and director of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine & Ultrasound, implemented a “Meds to Beds” approach: Instead of referring patients with hepatitis C to outpatient follow-up care after discharge, the obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine care team would begin the process required for an infectious disease specialist to initiate treatment before the patient was discharged.

To evaluate the effectiveness of this collaborative approach, Marks and first author Madeline McCrary, MD, an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases, reviewed medical records of 149 mothers who delivered babies at Barnes-Jewish Hospital between January 2020 and September 2023 and had tested positive for hepatitis C. Depending on the timing and availability of infectious disease specialists, the women either received immediate hepatitis C treatment while still in the hospital after giving birth or got a referral for an appointment at an outpatient infectious disease clinic or hepatology clinic after their discharge.

Overall, two-thirds of the patients who began treatment in the hospital successfully completed the full course of treatment — 2-3 months of antiviral medication — compared with about one-third of the outpatient referral group. The researchers found that over half of postpartum mothers in the outpatient referral group did not attend the follow-up appointment. The researchers measured successful treatment completion with a lab test confirming that the patient was no longer positive for hepatitis C or with a patient’s report that they had taken the full course of antiviral medication.

“Curing hepatitis C in these mothers has a huge ripple effect — it protects their health, their families and their future pregnancies,” Kelly said. “That’s why we partnered with our infectious disease colleagues to rethink how we could close the gaps in treatment. This new study shows that simply bringing the medication to the patient’s bedside right after delivery dramatically reduces the number of patients lost along the way.”

WashU Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases and Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine have also partnered to integrate infectious diseases care into obstetrics clinics, including implementing new guidelines endorsing shared decision-making around treating hepatitis C during pregnancy.

Exporting the ‘Meds to Beds’ program

Marks, Kelly and colleagues are working to train doctors at WashU Medicine to deploy this interdepartmental “Meds to Beds” program, not only for postpartum mothers but for all patients with untreated hepatitis C. Since 2023, WashU Medicine doctors led by Marks have built up a hepatitis C virus care navigation and treatment program at Barnes-Jewish that incorporates the “Meds to Beds” model and arranges for expedited post-treatment follow-up in local communities to ensure patients are cured. The program has delivered medications to bedside for more than 200 patients, representing an important advance in hepatitis C care.

Beyond WashU Medicine and Barnes-Jewish, Marks points to the future exportability of the new approach, which could also be applied to other infectious diseases.

“We can’t be afraid to try a new model of care when what we stand to gain is better health for the whole community,” Marks said. “We’re teaching our trainees to treat what’s in front of them, especially communicable diseases. As they’re completing the program here, we’re seeing them get recruited to bring this successful model elsewhere. It’s a gradual process, but based on the success we’re already seeing, this momentum will continue to build over time.”

McCrary LM, Leydh Z, Curtis MR, Elrod-Gallegos J, Kojima P, Karpman L, Cain J, Vora K, Bongu J, Habrock-Bach T, Durkin MJ, Trammel C, Kelly JC, Marks L. Association between postpartum inpatient consultation versus outpatient referral with hepatitis C treatment completion. Obstetrics & Gynecology Open. September 11, 2025.

This work was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

Dr. Kelly receives funding from NIDA (5R21DA057493-02, 1R61DA062321-01); NICHD (1R01HD113199-01). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Drs. McCrary and Marks report funding from Gilead’s Frontlines of Communities in the United States (FOCUS) program. FOCUS funding supports HIV, HCV, and HBV screening and linkage to the first medical appointment after diagnosis; FOCUS funding does not support any activities beyond the first medical appointment and is agnostic to how FOCUS partners handle subsequent patient care and treatment.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with 2,900 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 83% since 2016. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently within the top five in the country, with more than 1,900 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations. WashU Medicine physicians exclusively staff Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals — the academic hospitals of BJC HealthCare — and treat patients at BJC’s community hospitals in our region. WashU Medicine has a storied history in MD/PhD training, recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

Originally published on the WashU Medicine website