For Jen Heemstra, the “aha moment” came early in her career, when a student in her lab got the results from a qualifying exam — and melted down.

The person was angry about the feedback received — and letting everyone know it. At the same time, the more senior students in the group, who had already passed their exams, were frustrated by how the situation was distracting them from their work. Another faculty member warned her that her lab was at risk of social implosion. Heemstra’s stomach sank. She closed her office door and frantically Google-searched “conflict resolution.”

Years later, now as chair of the Department of Chemistry in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, Heemstra is grateful for the perspective she gained during that uncomfortable experience. It set her on a journey of personal improvement and learning, leading her to collect and document many of these lessons in her new book, “Labwork to Leadership: A Concise Guide to Thriving in the Science Job You Weren’t Trained For” (Harvard University Press, Aug. 5, 2025).

“You might be wondering: How well did I manage that first conflict in my research group? Not very well,” she writes in the book. “But I encourage you to also ask the question: How well did I manage the next conflict in my group? Much better.”

What made the difference? For Heemstra, learning conflict-resolution skills — and a whole suite of other “people skills.” Now, Heemstra believes that anyone — independent of whether they hold a formal title or think of themselves as a leader — can learn and develop the skills to be an excellent one.

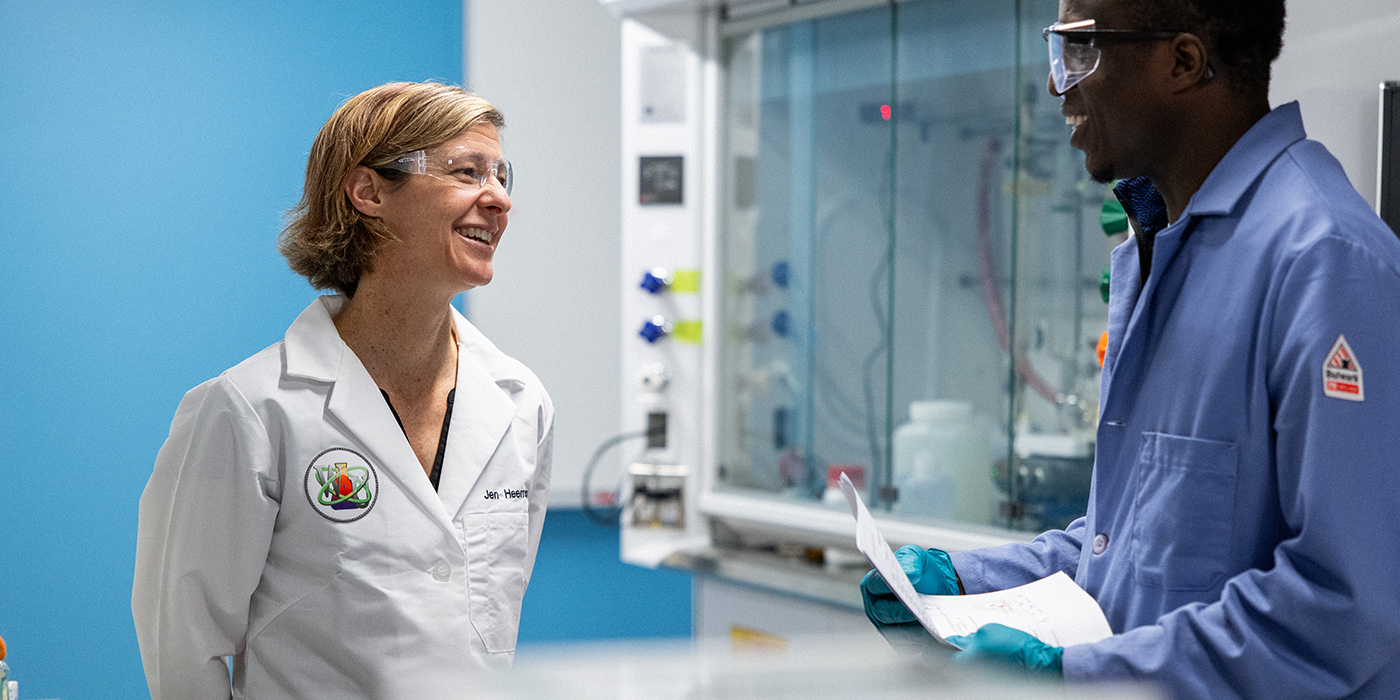

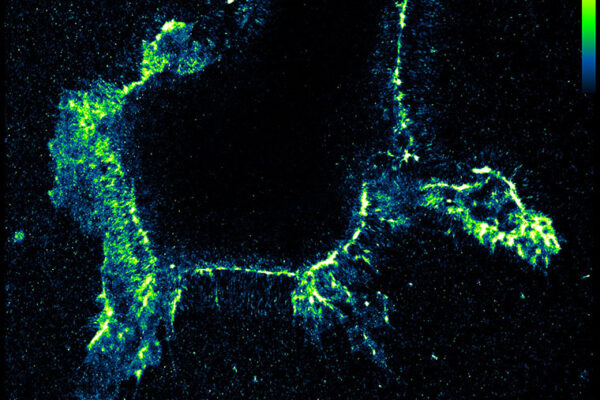

“In science, you’re told that if you are going to become a professor, you will be a researcher, and you will need research training,” said Heemstra, the Charles Allen Thomas Professor of Chemistry and the leader of a lab harnessing the properties of nucleic acids and proteins for applications in biosensing and bioimaging. “And then, as a faculty member, you find yourself running a research group and you quickly realize, ‘Wow, I actually have a people management and leadership job. And I wasn’t prepared for it.’”

Heemstra came to recognize herself and many others in her position as “accidental leaders” — people who weren’t seeking out a leadership job, but come to the startling recognition that they have one.

Universities are getting better about recognizing this gap, she said, but there’s still a lot of room for improvement. “The amount of training we get in leadership compared to the fraction of our job that is leading other people is disproportionately small,” Heemstra said.

Starting 10 years ago, Heemstra began devouring books and podcasts on leadership topics and experimenting with recommended strategies in her own lab. She soon recognized that while these resources were helpful, the information was typically offered in the context of the business world rather than academia, and that other faculty might not enjoy reading on the topics as much as she does. This inspired her to write the book that she wished she’d had at the start of her career.

Heemstra makes a point that while leadership is often viewed as something that requires one to be extroverted or charismatic, anyone can thrive as a leader. The skills described in the book apply to people with a wide range of personalities and approaches.

“Being a leader — and a professor — isn’t necessarily about getting in front of 300 people and speaking eloquently,” Heemstra said. “It’s even more so about the individual interactions, coaching and encouraging students. Many of the leadership actions that I speak to in the book are things that are happening individually, like giving and receiving feedback or helping someone set goals and make a plan to achieve them.”

Importantly, Heemstra encourages people to think about how their own behavior as a leader creates a culture for those around them. For example, if faculty want to avoid scientific misconduct in their labs, how they react to failed experiments is critical.

“You’re under a lot of stress, and yes, a failed experiment is never good news,” Heemstra said. “But if you react really poorly, it leaves members of your lab feeling like they have to choose between continuing in their career or possibly committing misconduct. In comparison, if you take the news well and then work together to troubleshoot, then your lab members are more likely to tell you when things go wrong.”

The book is written in an informal, action-oriented style, organized into three sections: leading oneself, leading others, and training the next generation of leaders. The third part is what most excites Heemstra.

Five years from now, today’s graduate students are going to be leaders — whether in academia, industry, government or elsewhere. As a result, faculty have an opportunity to help break the cycle, Heemstra said.

“As we’re learning these skills for ourselves, we can also be teaching them to the people that we’re leading,” she said. “If we do that, then when our current students find themselves in leadership roles in the future, they will be more prepared for them.”

Heemstra said she is grateful to be at an institution that is at the forefront of creating change. As a department chair, she is continually inspired by working collaboratively with others. “My career goal is creating a healthier academic culture for the next generation of researchers,” she said. “If I achieve nothing else, I want to use the rest of my career to move the needle on that.”

WashU Medicine is hosting a book discussion on “Labwork to Leadership” with Jen Heemstra on Nov. 6 and 7. Read more on the event website.