Performance artist Tim Youd follows two rules when retyping books for his “100 Novels Project.” Rule No. 1: He must use the same make and model of typewriter originally used by the author. Fortunately for Youd, he has 100 typewriters in his California studio and a close friendship with the world’s preeminent typewriter historian.

And Rule No. 2: He must retype the novels in a significant location — the Chicago stockyards for “The Jungle,” William Faulkner’s front yard for “The Sound and the Fury,” St. Louis’ Bellefontaine Cemetery for “Naked Lunch.”

And now KWUR, WashU’s student radio station, for “The Dick Gibson Show,” Stanley Elkin’s bawdy classic about a late-night disc jockey.

From Sunday, April 13, through May 1, Youd will host the overnight show “Up All Night on KWUR with Tim Youd,” typing, word for word, Elkin’s 1971 novel on a single sheet of paper. The live broadcast also will feature audio recordings of Elkin reading from his works and Youd’s interviews with acclaimed artists, authors and critics. Featured guests include Richard Polt, the typewriter historian who determined that Elkin used a Royal typewriter; Molly Elkin, a labor lawyer and daughter of Stanley and Joan Elkin; and Joel Minor, WashU Libraries curator of the Modern Literature Collection and manuscripts, home of the recently completed Stanley Elkin Papers.

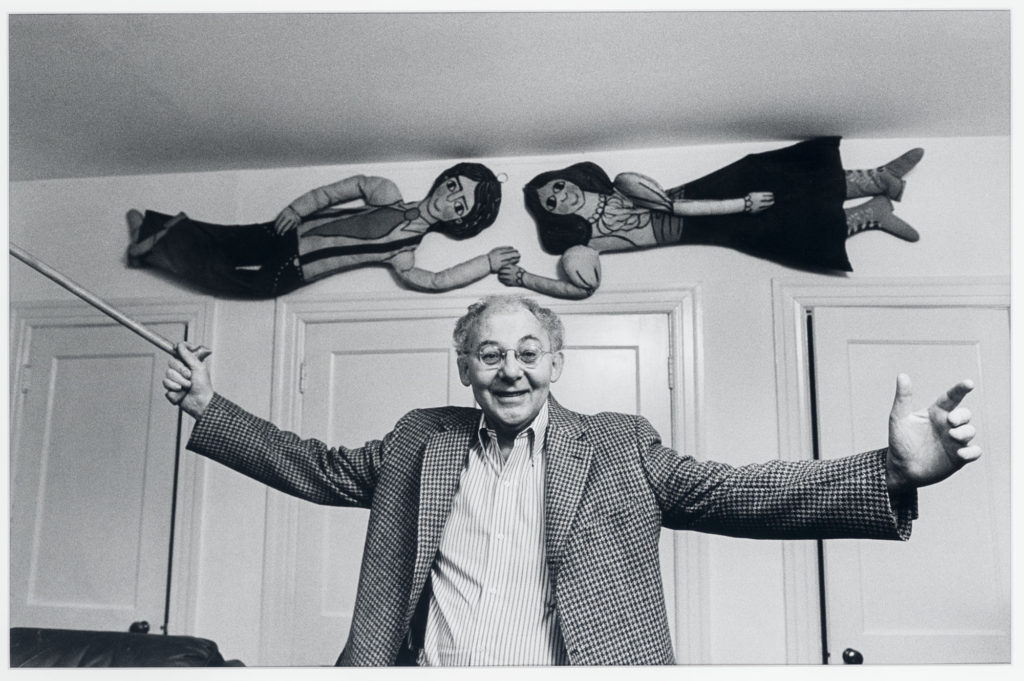

Youd’s performance will be streamed on KWUR; Youd also will post his interview on his website. “Up All Night” runs in conjunction with the WashU Libraries exhibit “Stanley and Joan Elkin’s Artistic Kingdom.” Stanley Elkin taught in the Department of English in Arts & Sciences from 1960 until his death in 1995.

Here, Youd shares the genesis of this unusual project, his affection for the work of Stanley Elkin how he plans to stay up all night.

This will be the 84th novel in your series. Why are you doing this?

The deep-down reason is compulsion. For me, I’ve always loved to read. I had a life becoming an artist. I worked on Wall Street, then I came to L.A. to produce movies and make commercials. And I was really unhappy. I would ask myself, ‘Am I going to do this forever?’ As a kid, I always made art, and that made me happy, so I decided I should go back to that. But even before art, there was reading and the place reading can take you. At a certain point, I was able to connect the two. I realized, ‘Wow, I can make art and read at the same time, and reading is going to be the art.’

The end results of your work are these fascinating diptychs that are wrinkled and saturated with ink and evoke an open book. What is it about text that you find compelling?

When we read, something happens to us on a biochemical level. The brain is changed by reading. It’s kind of like a blot on our brain; the cells have altered a little bit and there’s texture there. I see my diptychs as a metaphor for what happens to the brain when we read. All of the words are present, layered on top of each other, kind of like the layering of pages onto our brains. The words keep building up — not just one book, but the thousands of books we read over the course of our lives.

This book put Elkin on the map, and critics credit for it for presaging talk radio and the internet. Yet the novel isn’t widely read today. Why did you pick it?

I was lucky enough to get a show with the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis back in 2018, and I started looking into St. Louis authors, and Elkin popped up for me. I read ‘The Franchiser’ and I loved it. It resonated so deeply for me, that sort of cynical but humorous take on life that so many businessmen have to find to justify getting out of bed in the morning. He just nailed it. I ended up typing ‘The Franchiser’ for that show on campus in Duncker Hall (longtime home to the WashU English Department). Over time, I became a big Elkin fan and carried around this idea that it would be great to do ‘The Dick Gibson Show’ on a Midwestern radio station.

So you are on air for up to seven hours every night. How are you going to be able to hold up?

I did do an all-night retyping fairly early in the project, but it was easier when I started at 45 as opposed to now when I’m 57. Those first couple of nights will be a beating. I’m going to be a zombie when I’m not typing.