As highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza continues to spread in the U.S., posing serious threats to dairy and poultry farms, both farmers and public health experts need better ways to monitor for infections, in real time, to mitigate and respond to outbreaks. Now, thanks to research from Washington University in St. Louis published in a special issue of ACS Sensors on “breath sensing,” virus trackers have a way to monitor aerosol particles of H5N1.

To create their bird flu sensor, researchers in the lab of Rajan Chakrabarty, a professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering at WashU’s McKelvey School of Engineering, worked with electrochemical capacitive biosensors to improve the speed and sensitivity of virus and bacteria detection.

Their work is crucially timed as the avian virus has taken a dangerous turn over the past year to being transmitted via airborne particles to mammals, including humans. The virus has been proven deadly in cats, and there has been at least one case of a human death from H5N1.

“This biosensor is the first of its kind,” said Chakrabarty, speaking of the technology used to detect airborne virus and bacteria particles. Scientists previously had to use slower detection methods with polymerase chain reaction DNA tools.

Chakrabarty noted that conventional test methods can take more than 10 hours — “too long to stop an outbreak.”

The new biosensor works within five minutes, preserving the sample of the microbes for further analysis and providing a range of the pathogen concentration levels detected on a farm. This allows for immediate action, Chakrabarty said.

Time is of the essence when preventing a viral outbreak. When the lab started working on this research, H5N1 was only transmissible through contact with infected birds.

“As this paper evolved, so did the virus; it mutated,” Chakrabarty added.

The United States tracks animal health and the pathogen outbreaks on farms via the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), which last reported that in the past 30 days, there have been at least 35 new dairy cattle cases of H5N1 in four states, mostly in California.

“The strains are very different this time,” Chakrabarty said.

If farmers suspect illness, they can send the animal to state agriculture department labs for testing. However, it’s a slow process that can be further delayed due to the backlog of cases as H5N1 overtakes poultry and dairy farms. Mitigation options include biosecurity measures such as quarantining animals, sanitizing facilities and equipment, and protective controls to limit animal exposure, including mass culling. The USDA also recently issued a conditional license for an avian flu vaccine, which could provide further relief to poultry farmers eager to lower egg prices.

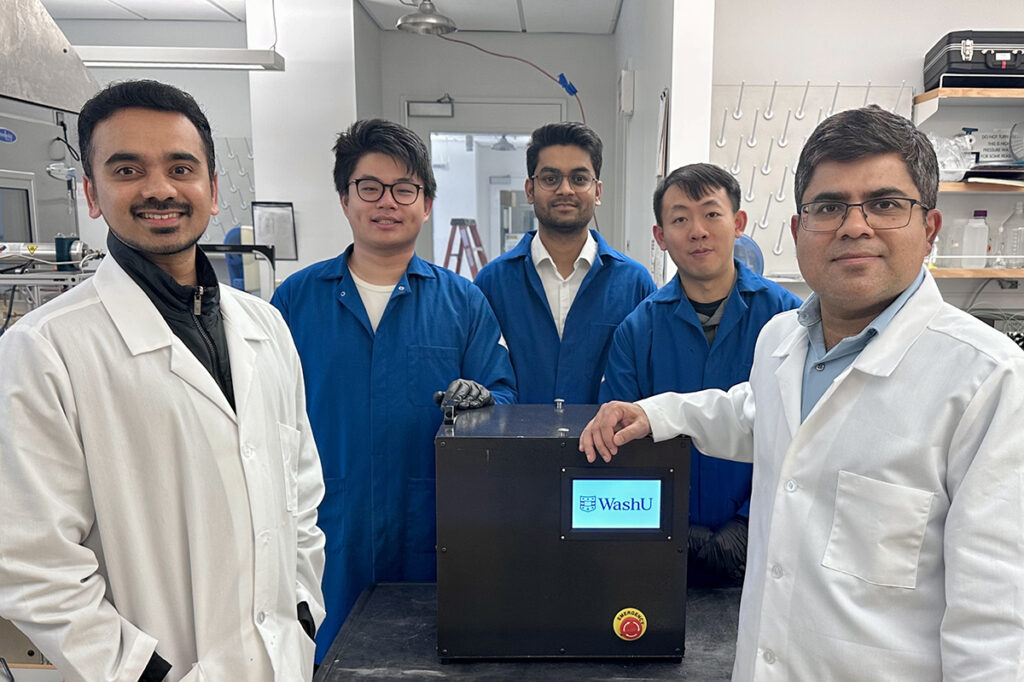

Chakrabarty is ready to introduce this biosensor to the world and said it was built to be portable and affordable for mass production.

How it works

The integrated pathogen sampling-sensing unit is about the size of a desktop printer and can be placed where farms vent exhaust from chicken or cattle housing. The unit is an interdisciplinary engineering marvel consisting of a “wet cyclone bioaerosol sampler” that originally was developed for sampling SARS-CoV-2 aerosols.

The pathogen-laden air enters the sampler at very high velocities and is mixed with the fluid that lines the walls of the sampler to create a surface vortex, thereby trapping the virus aerosols. The unit has an automated pumping system that sends the sampled fluid every five minutes to the biosensor for seamless virus detection.

Chakrabarty’s senior staff scientist, Meng Wu, along with graduate student Joshin Kumar, undertook the laborious task of optimizing the surface of the electrochemical biosensor to increase its sensitivity and stability for detection of the virus in trace amounts (less than 100 viral RNA copies per cubic meter of air).

The biosensor uses “capture probes” called aptamers, which are single strands of DNA that bind to virus proteins, flagging them. The team’s big challenge was finding a way to get these aptamers to work with the 2-millimeter surface of a bare carbon electrode in detecting the pathogens.

After months of trial and error, the team figured out the right recipe for modifying the carbon surface using a combination of graphene oxide and Prussian blue nanocrystals to increase the biosensor’s sensitivity and stability. The final step involved tying the modified electrode surface to the aptamer via crosslinker glutaraldehyde, which Xu and Kumar said is the “secret sauce” for functionalizing the surface of a bare carbon electrode to detect H5N1.

They added that one big advantage of the team’s detection technique is that it is nondestructive. After testing for the presence of a virus, the sample could be stored for further analysis by conventional techniques such as PCR.

The integrated pathogen sampling-sensing unit works automatically — a person doesn’t need to have expertise in biochemistry to use it. It is made with affordable and easy-to-mass-produce materials. The biosensor can provide concentration ranges of H5N1 in the air and alert operators to disease spikes in real time. Xu said knowledge of the levels can be used as a general indicator of “threat” in a facility and let operators know if the pathogen balance has tipped into dangerous levels.

That ability to offer a range of virus concentration is another “first” for sensor technology. Most importantly, it can potentially scale up to find many other dangerous pathogens all in one device.

“This biosensor is specific to H5N1, but it can be adapted to detect other strains of influenza virus (e.g., H1N1) and SARS-CoV-2 as well as bacteria (E. coli and pseudomonas) in the aerosol phase,” Chakrabarty said. “We have demonstrated these capabilities of our biosensor and reported the findings in the paper.”

The team is working to commercialize the biosensor. Varro Life Sciences, a St. Louis biotech company, has consulted with the research team during the biosensor’s design stages to facilitate its possible commercialization in the future.

Kumar J, Xu M, Li YA, You SW, Doherty BM, Gardiner WD, Cirrito JR, Yuede CM, Benegal A, Vahey MD, Joshi A, Seehra K, Boon ACM, Huang YY, Puthussery JV, Chakrabarty R. Capacitive Biosensor for Rapid Detection of Avian (H5N1) Influenza and E. coli in Aerosols. ACS Sensors, online Feb. 21. DOI: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssensors.4c03087

Funding for this research was provided by Flu Lab.