Treatment for chronic pain still relies heavily on opioids. While effective, they are highly addictive and potentially deadly if misused. In the quest to develop a safe, effective alternative to opioids, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Stanford University have developed a compound that mimics a natural molecule found in the cannabis plant, harnessing its pain-relieving properties without causing addiction or mind-altering side effects in mice.

While more studies are needed, the compound shows promise as a nonaddictive pain reliever that could help the estimated 50 million people in the U.S. who suffer from chronic pain. The study is published March 5 in Nature.

“There is an urgent need to develop nonaddictive treatments for chronic pain, and that’s been a major focus of my lab for the past 15 years,” said the study’s senior author Susruta Majumdar, a professor of anesthesiology at WashU Medicine. “The custom-designed compound we created attaches to pain-reducing receptors in the body but by design, it can’t reach the brain. This means the compound avoids psychoactive side effects such as mood changes and isn’t addictive because it doesn’t act on the brain’s reward center.”

Opioids dull the sensation of pain in the brain and hijack the brain’s reward system, triggering the release of dopamine and feelings of pleasure, which make the drugs so addictive. Despite widespread public health warnings and media attention focused on the dangers of opioid addiction, numerous overdose deaths still occur. In 2022, some 82,000 deaths in the U.S. were linked to opioids. That’s why scientists are working so hard to develop alternative treatments for pain.

“For millennia, people have turned to marijuana as a treatment for pain,” explained co-corresponding author Robert W. Gereau, the Dr. Seymour and Rose T. Brown Professor of Anesthesiology and director of the WashU Medicine Pain Center. “Clinical trials also have evaluated whether cannabis provides long-term pain relief. But inevitably the psychoactive side effects of cannabis have been problematic, preventing cannabis from being considered as a viable treatment option for pain. However, we were able to overcome that issue.”

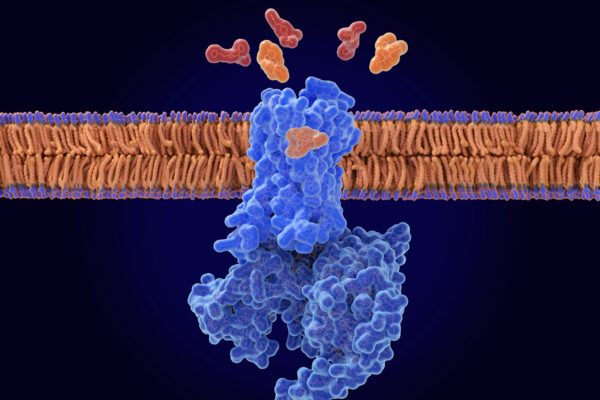

The mind-altering properties of marijuana stem from natural molecules found in the cannabis plant referred to as cannabinoid molecules. They bind to a receptor, called cannabinoid receptor one (CB1), on the surface of brain cells and on pain-sensing nerve cells throughout the body.

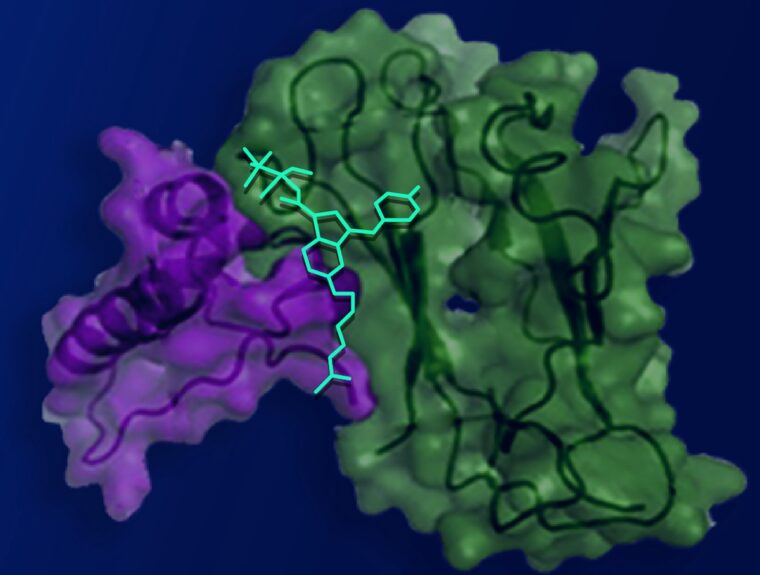

Working with collaborators at Stanford University, co-first author Vipin Rangari, a WashU Medicine postdoctoral research associate in Majumdar’s laboratory, designed a cannabinoid molecule with a positive charge, preventing it from crossing the blood-brain barrier into the brain while allowing the molecule to engage CB1 receptors elsewhere in the body. By modifying the molecule such that it only binds to pain-sensing nerve cells outside of the brain, the researchers achieved pain relief without mind-altering side effects.

They tested the modified synthetic cannabinoid compound in mouse models of nerve-injury pain and migraine headaches, measuring hypersensitivity to touch as a proxy for pain. Applying a normally non-painful stimulus allows researchers to indirectly assess pain in mice. In both mouse models, injections of the modified compound eliminated touch hypersensitivity.

For many pain relievers, particularly opioids, tolerance to the medications over time can limit their long-term effectiveness and require higher doses of medication to achieve the same level of pain relief. In this study, the modified compound offered prolonged pain relief — the animals showed no signs of developing tolerance despite twice-daily treatments with the compound over the course of nine days. This is a promising sign that the molecule could be used as a nonaddictive drug for relief of chronic pain, which requires continued treatment over time.

Eliminating the compound’s tolerance resulted from the bespoke design of the compound. The Stanford collaborators performed sophisticated computational modeling that revealed a hidden pocket on the CB1 receptor that could serve as an additional binding site. The hidden pocket, confirmed by structural models, leads to reduced cellular activity related to developing tolerance compared to the conventional binding site, but it had been considered inaccessible to cannabinoids. The researchers found that the pocket opens for short periods of time, allowing the modified cannabinoid compound to bind, thus minimizing tolerance.

Designing molecules that relieve pain with minimal side effects is challenging to accomplish, said Majumdar. The researchers plan to further develop the compound into an oral drug that could be evaluated in clinical trials.

Rangari VA, O’Brien ES, Powers AS, Slivicki RA, Bertels Z, Appourchaux K, Aydin D, Ramos-Gonzalez N, Mwirigi I J, Lin L, Mangutov E, Sobecks BL, Awad-Agbaria Y, Uphade MB, Aguilar J, Peddada TN, Shiimura Y, Huang XP, Folarin-Hines J, Payne M, Kalathil A, Varga BR, Kobilka BK, Pradhan AA, Cameron MD, Kumar KK, Dror RO, Gereau IV RW, and Majumdar S. A cryptic pocket in CB1 drives peripheral and functional selectivity. Nature. March 5, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08618-7

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers R34NS126036, F32DA051160 and K99DA056691; the PhRMA Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship, grant number 100001797. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with 2,900 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 56% in the last seven years. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently within the top five in the country, with more than 1,900 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations and who are also the medical staffs of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals of BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine has a storied history in MD/PhD training, recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

Originally published on the WashU Medicine website