A new study outlines the ways by which city life may be shaping the evolution of urban coyotes, the highly adaptable carnivores spotted in alleyways from Berkeley, Calif., to the Bronx, in New York.

Historically, evolution was thought to occur on vast chronological scales. But scientists now understand that evolution can happen within just a few generations. Urban areas offer a unique glimpse into how evolution functions on smaller timescales and how species adapt to human presence and novel environments.

Some species, like coyotes, seem particularly well suited to living alongside humans.

“Coyotes are doing really well in urban spaces,” said Elizabeth Carlen, a postdoctoral fellow with the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University in St. Louis and senior author of a study in Genome Biology and Evolution.

“Given the close evolutionary relationship between coyotes and domestic dogs, we leveraged the dog genome to think about what genes could be under selection in urban areas and how they might be changing,” Carlen said.

“For coyotes in particular, the ecological differences between urban and rural individuals have been well characterized,” said Samantha Kreling, a PhD candidate at the University of Washington, first author of the new study. “However, while we know that genetic and ecological differences exist, few studies have looked at specific genes or the genome regions that may be affected. In our study, we present candidate genes to investigate for adaptive evolution in urban coyotes.”

The candidate gene approach involves researchers identifying particular genes of interest to sequence and compare. While whole-genome and epigenome sequencing are the gold standard for understanding evolutionary change and adaptation, these methods can be cost-prohibitive — especially for wildlife-focused budgets, Carlen explained.

For studies with limited budgets, targeting specific candidate genes for sequencing can allow testing of hypotheses while maintaining sufficient sample sizes to have statistical power. Carlen and Kreling’s new study provides examples of life history traits that may be under selection in urban coyotes as well as a list of candidate genes that have the potential to be implicated — including genes related to diet, health, thermoregulation, behavior, cognition and reproduction.

Take, for example, the genes related to the coyote’s eating habits.

While the majority of a rural coyote’s diet consists of rabbits, mice and other small mammals, urban coyotes have easy access to outdoor pet food and human refuse. This likely translates into higher consumption of glucose and starches, WashU’s Carlen said.

If sugar intake is sufficient to cause insulin resistance and subsequent negative health outcomes, then the genes that help regulate insulin sensitivity and production may be selected for. Likewise, urban coyotes probably need to be able to digest more starch, as seen in previous research with domestic dogs, who have increased copy numbers of AMY2B, a gene responsible for amylase production and increased starch digestion efficiency.

Living alongside humans

Coyotes are increasingly common in urban areas throughout the United States, but local population trends vary. “We do know that we’re getting more coyotes on the East Coast because wolves have been displaced,” Carlen said.

“In these places, we’re seeing more coyotes because they’re occupying the niche space that previously would have been occupied by wolves,” she said. “Because if a wolf shows up in the Bronx, it’s going to be killed. But coyotes can fit in.”

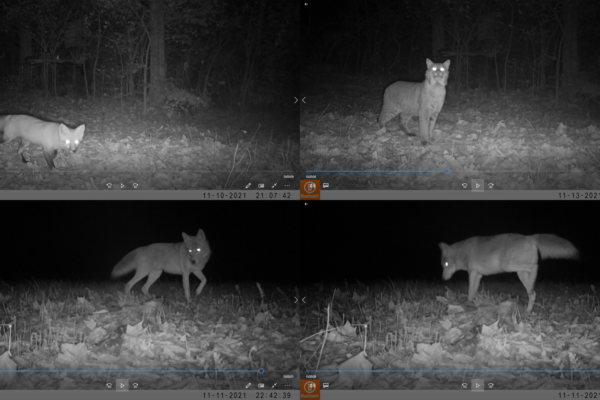

In St. Louis, another project supported by the Living Earth Collaborative, the Forest Park Living Lab, is using motion-triggered wildlife cameras and GPS collars to study coyotes in and around Forest Park, near WashU.

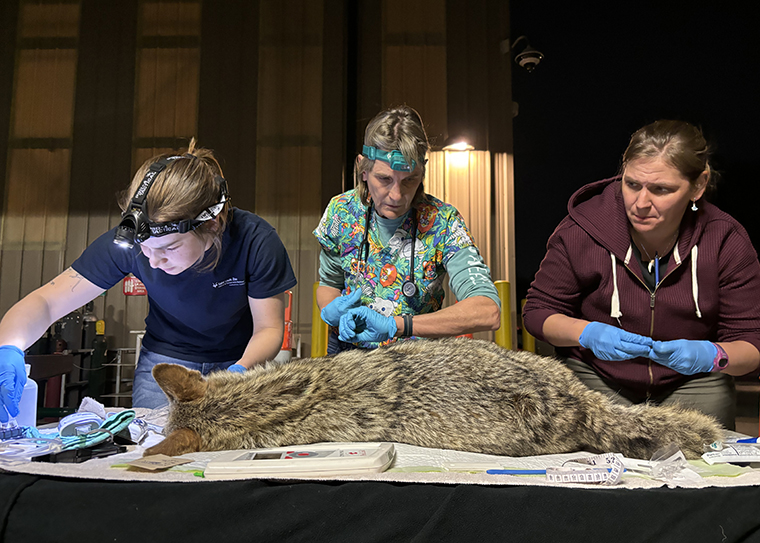

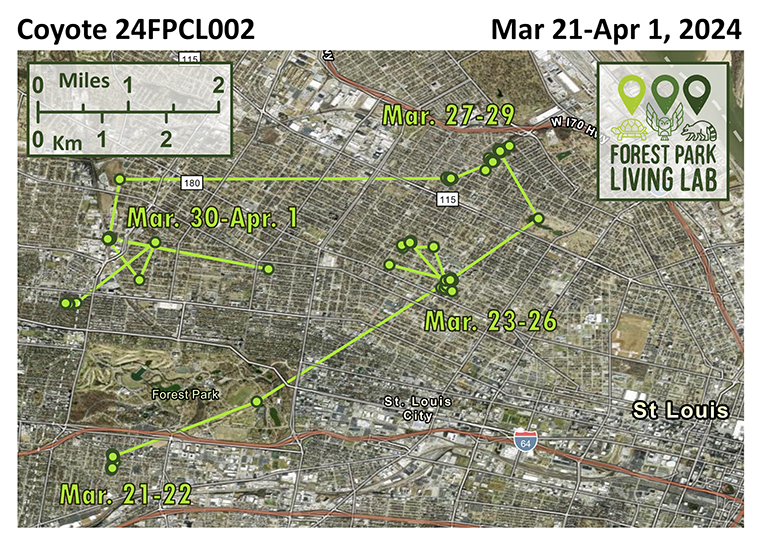

In 2024, members of the local community followed along as a reporter and photographer from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described the scientists’ efforts trapping and tracking a visiting male coyote and a female mother of pups. Tracking data was supposed to be collected for one year, but unfortunately each adult coyote died within months of being released.

Studying urban coyotes is interesting and challenging, said Carlen, who has contributed to local coyote research led by partner organizations including the Saint Louis Zoo. The animals are smart and tend to want to hide from people.

“There is a lot of misplaced fear around coyotes,” she said. “This is a decently large animal to be living alongside humans in our urban spaces, but I think that they are unfairly persecuted.”

She hopes this study will serve as a guideline for scientists researching urban adaptation in coyotes, as well as a starting point for other urban evolutionary biologists studying other species to create their own candidate gene catalog.

“While we have seen continued growth in the field of urban evolution, research work linking specific genes to adaptation in urban regions is still relatively unexplored,” Carlen said.