Nobody goes into emergency medicine expecting to have an easy career. But for some doctors, including “Max,” an ER shift can include stressors beyond the high-paced demand to save lives. As a Black doctor, Max regularly encounters hostility from patients who question his credentials, make racist comments or demand to be seen by other doctors. Making a bad situation worse, Max’s hospital offers no policies to address the mistreatment.

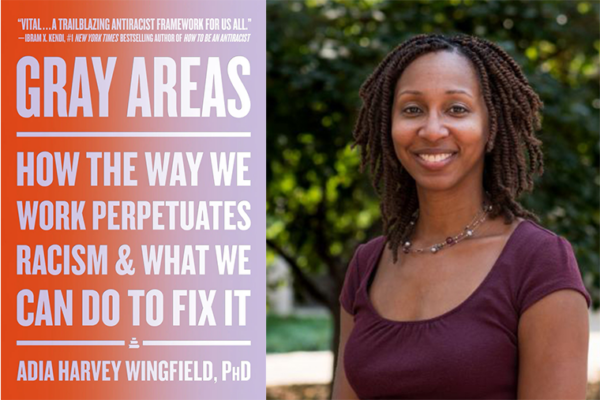

Renowned sociologist Adia Harvey Wingfield, the Mary Tileston Hemenway Professor and vice dean of faculty development and diversity in Arts & Sciences, interviewed Max and hundreds of other Black professionals for her latest book, Gray Areas: How the Way We Work Perpetuates Racism and What We Can Do to Fix It. The book explains the continued need for diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies in a wide range of professional settings, why current approaches fail to support workers, and how employers can do better for all their employees.

The problem with ‘colorblindness’ at work

Using Max’s case as an example, Wingfield explains how employers’ attempts to be colorblind backfire. Like many workplaces, the hospital has a hierarchical, seemingly colorblind structure. As a doctor, Max is positioned at the top of the hierarchy and, on paper, treated equally to others within his rank. But that approach doesn’t consider the reality of Max’s experience.

Max encounters explicit, direct racism at work — the types of behaviors that are easy to condemn as prejudiced. In a more subtle way, by not supporting Max or even recognizing the disrespect he faces, his employer, Wingfield says, reinforces that racism.

“The decision to be a colorblind organization may on the face of it seem like an approach that we want, but if we prematurely move into that space, we ignore the fact that we aren’t a colorblind society,” Wingfield says. “One of the things that we know from research is that attempts to be colorblind ultimately serve to reinforce racial inequalities that are already present.”

Racial inequalities persist even in professional settings that claim to value diversity or where workers don’t encounter explicit racism, Wingfield says. Take “Constance,” a chemical engineer and professor at a research university. In her line of work, Constance doesn’t encounter the direct hostility that Max experiences. Nonetheless, her identity has negative effects on her professional life.

“As a Black woman, Constance ends up feeling very isolated, even though the culture is one that’s in a presumably liberal space,” Wingfield says. “It still is an environment where the gray areas of that organizational culture make it difficult for Constance to secure mentors and to receive the support that she needs in order to advance in the job.”

Bringing ‘gray areas’ to light

The gray areas Wingfield references throughout her book often relate to personal networks and relationships. These relationships fall outside of job descriptions, but they play a major role in finding work opportunities, getting hired, fitting into an office culture and advancing into leadership roles.

“Relationships and networks matter more than ever,” Wingfield states in her book. “Today, gray areas are nearly — or sometimes equally — as important as one’s capacity to perform the technical requirements of a job.”

“Often our hiring processes work through our social networks,” she says. “And we know that because our social networks are so highly segregated, Black workers often miss out on being included in references and referrals.”

Gray Areas

How the Way We Work Perpetuates Racism and What We Can Do to Fix It

Corporations have poured billions of dollars into DEI efforts in recent years, but for the most part haven’t made substantial progress in increasing diversity in leadership roles or reaching other equity-related goals. One reason, Wingfield explains, is that the DEI programs many organizations put into place — things like high-priced diversity consultants and mandated one-day diversity trainings — can’t address the ways that many personal networks remain stratified along racial lines.

A better way: The diversity task force

Instead of top-down solutions, Wingfield recommends that employers create diversity task forces to identify workplace-specific DEI needs and solutions. Such task forces are made up of workers from within the organization who understand the existing culture and challenges.

“When they are pulled from workers throughout all levels of the organization, given resources and given mandates to make suggestions for potential change, diversity task forces actually get people on the same side working together to identify where pain points are in the organization,” Wingfield says.

If the task force identifies a lack of diverse candidates coming into the company, it may be time to rethink typical recruitment patterns and actively look beyond personal networks.

“I would encourage them to broaden their hiring approaches to include historically Black colleges and universities,” Wingfield says. “We know that there are a plethora of highly qualified, very motivated young people coming out of those arenas.”

If the company has trouble retaining or advancing underrepresented professionals, it should consider broadening mentoring programs to include all employees.

“In many cases, companies either make mentoring programs invitation only, and they target people who are construed as high performers, or they just let mentoring programs happen organically,” Wingfield says. “In both cases, there’s a high likelihood that leaders may miss people who want and are interested in mentoring but who still exist outside of those networks.”

All of these potential solutions benefit both workers and employers, Wingfield says. As she wrote recently in The Conversation, “Companies with more racial and gender diversity among managers boast more profitability and more innovation than those without.”

Despite the continued need and far-reaching benefits, workplace DEI initiatives face ongoing cultural backlash and legal scrutiny. Importantly, many of the evidence-based approaches Wingfield lays out remain viable in a changing legal landscape.

Each chapter of Gray Areas concludes with takeaways and checklists for human resources directors, senior managers, DEI practitioners and colleagues. To successfully create and maintain inclusive workplaces, she says, employees at every level should recognize the gray areas that underpin professional life.