It was April 1976 and the Pirates needed a spark. Right fielder Dave “The Cobra” Parker strolled into the clubhouse. “If you hear any noise,” read the custom T-shirt he’d had printed at a nearby record shop, “it’s just me and the boys boppin.”

The Pirates finished nine games behind the Phillies that season but Parker’s wordsmithing gained a life of its own. In 2022, MLB.com called it “the most legendary baseball T-shirt of all time.” The episode also speaks to deep ties between baseball and Black popular culture. Parker, known for his quick wit, was riffing on lyrics to “Mothership Connection (Star Child),” the Afrofuturist classic released a few months earlier by funk icons Parliament.

“The story of Black baseball is important social history,” says Gerald Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “That’s unavoidable in part because of racism. That is why there were separate leagues. But it is important to connect the players to elements of Black culture. For instance, the interaction between Black baseball and jazz, Black baseball and hip hop. That is vital to understanding how Black baseball is part of the fabric of Black cultural life.”

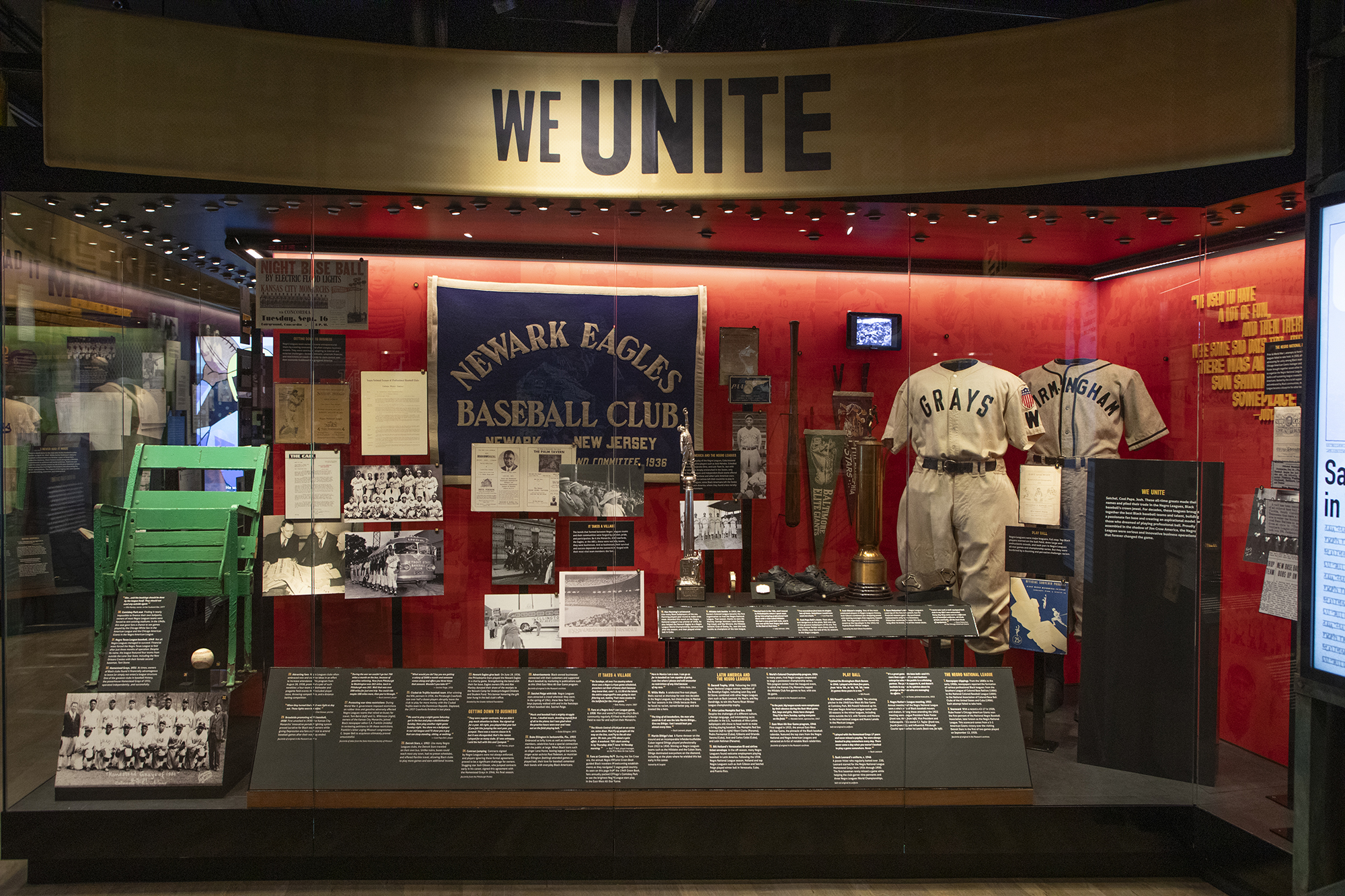

Early is discussing The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball, a new exhibition that opened May 25 at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Over the last several years, Early has served as a curatorial consultant for the exhibit, which unfolds through artifacts, interactive displays and — critically — through extensive quotations from players, managers, team owners and fans.

“We didn’t want a curator voice-over,” Early says. “The idea was to have people who were in the game relating their own experiences of the game.”

“My skin is against me. … The race prejudice is so strong that my Black skin barred me.”

— Bud Fowler, circa 1880s, widely considered the first Black Professional player

Establishing the line

One of the exhibit’s earliest voices belongs to Bud Fowler, widely considered the first Black professional player. Fowler, who was raised in Cooperstown, played for the mostly white Lynn Live Oaks in Massachusetts, as well as for the Keokuk Hawkeyes, the Topeka Capitals and Terre Haute Hoosiers, among many others.

In late June 1887, Fowler was hitting .350 for the International League’s Binghamton Bingos when nine white teammates petitioned for his removal. Just weeks later, league owners barred new contracts for African American players, a move soon followed by the American Association and the National League.

Baseball’s color line was firmly in place.

“We used to have a lot of fun, and then there were some sad days, too, but there was always sun shining someplace.”

— William Julius “Judy” Johnson, who played 17 seasons in the negro leagues from 1921-1937

They persevered

One impetus for creating The Souls of the Game was Major League Baseball (MLB)’s decision, in 2020, to recognize seven different Negro leagues, spanning the years 1920 to 1948, as major leagues. Just days after the opening, MLB announced that it had formally incorporated available statistics for more than 2,300 Negro league players.

The effects were profound. Josh Gibson, the power-hitting catcher for Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, overtook Ty Cobb as MLB’s all-time batting leader. Satchel Paige, who had a 1.01 earned-run average for the 1944 Kansas City Monarchs, is officially credited with the third-lowest single-season ERA. Minnie Miñoso, who spent three seasons with the New York Cubans before going to Cleveland in 1949, at last joined the 2,000-hit club.

“Black people — here in the United States, in the Caribbean, and in Latin America — were really committed to playing this game,” Early says. “Black Americans created leagues to play this game, a challenging thing to do. That’s an amazing story.” Black or white, sports fan or not, “that commitment, that dedication should mean something to you.”

“Today, and every day, we come together as brothers, as equals — all with the same goal — to level the playing field.”

Andrew Mccutcheon, five-time all-star playing in his 16th MLB season

Confronting modern challenges

Back in Cooperstown, “Souls of the Game” dedicates its largest display to Jackie Robinson, whose 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers — nearly 60 years after Fowler’s banishment — finally reintegrated baseball.

At Early’s suggestion, the exhibition features Robinson’s Spingarn Medal, the NAACP’s highest honor, which he received in 1956. Also included are photos, newspaper clippings, a Dodgers jersey and — further underlining links between baseball and popular culture — pages from a comic book illustrating Robinson’s life. (Early personally donated a complete run of that series, released by Fawcett Publications between 1949 and 1952, to WashU’s Olin Library.)

Souls of the Game also confronts recent challenges. It highlights Phillies outfielder Andrew McCutchen, who, in July 2020, after months of protests following the death of George Floyd, spearheaded a league-wide racial justice “moment of unity.” It highlights Dodgers outfielder Mookie Betts, who, in 2022 — the 75th anniversary of Robinson’s signing — became the talk of the All-Star Game thanks to a T-shirt proclaiming, “We need more Black people at the stadium.”

“It was important to capture the post-George Floyd world,” Early says, and to address “the issue of Black people not being as engaged with the game as they were 50, 60 or 70 years ago. Understanding that estrangement is crucial.”

Bookending the exhibit are a pair of multimedia displays. The first tells the story of the 1955 Cannon Street All-Stars, an African American Little League team from Charleston, South Carolina, that, thanks to strategic forfeits by white competitors, was denied a chance to play in that year’s World Series.

The second display features more than 30 contemporary interviews on a variety of themes, from “Facing Racism” and “Representation Matters” to “Passing the Torch.”

“It’s not just players,” Early says of the latter, “but Black parents, Black students, young people playing the game. That was something I really emphasized. You need to get ordinary Black people to talk about the game.

“I said, ‘You need to have the voices of Black children in the exhibit,’” Early says. “I am happy that the curators did just that.”