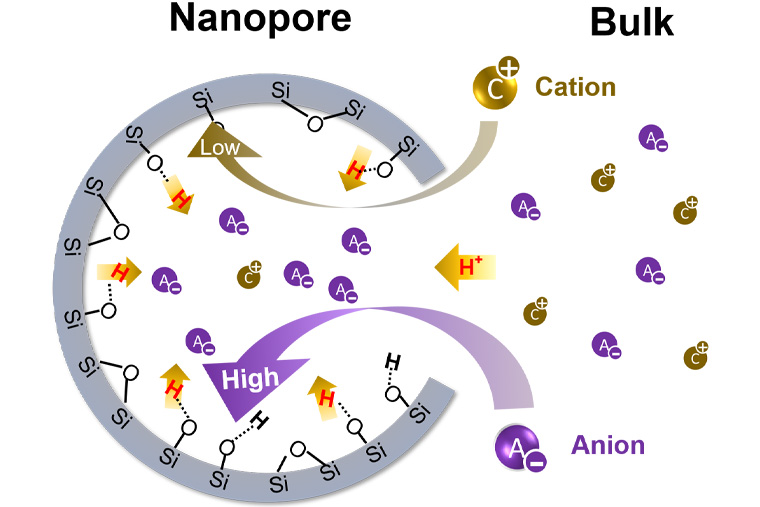

There is an entire aqueous universe hidden within the tiny pores of many natural and engineered materials. Research from the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis has shown that when such materials are submerged in liquid, the chemistry inside the tiny pores — known as nanopores — can differ critically from that in the bulk solution.

In fact, in higher-salinity solutions, the pH inside of nanopores can be as much as 100 times more acidic than in the bulk solution.

The research findings were published Aug. 22 in the journal CHEM.

A better understanding of nanopores can have important consequences for a variety of engineering processes. Think, for example, of clean-water generation using membrane processes; decarbonization technologies for energy systems, including carbon capture and sequestration; hydrogen production and storage; and batteries.

Young-Shin Jun, a professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering, and Srikanth Singamaneni, the Lilyan & E. Lisle Hughes Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science, wanted to understand how pH — the measure of how acidic or basic a liquid is —in nanopores differed from that of the bulk liquid solution they are submerged in.

“pH is a ‘master variable’ for water chemistry,” Jun said. “When it is measured in practice, people are really measuring the pH of the bulk solution, not the pH inside the material’s nanopores.

“And if they are different, that is a big deal because the information about the little tiny space will change the entire prediction in the system.”

Read more on the engineering website.

This work is supported by American Chemical Society’s Petroleum Research Fund (62756-ND5) and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA95501910394).

The McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis promotes independent inquiry and education with an emphasis on scientific excellence, innovation and collaboration without boundaries. McKelvey Engineering has top-ranked research and graduate programs across departments, particularly in biomedical engineering, environmental engineering and computing, and has one of the most selective undergraduate programs in the country. With 140 full-time faculty, 1,387 undergraduate students, 1,448 graduate students and 21,000 living alumni, we are working to solve some of society’s greatest challenges; to prepare students to become leaders and innovate throughout their careers; and to be a catalyst of economic development for the St. Louis region and beyond.